The Pharmacist’s Quick Rundown on Preeclampsia vs Eclampsia

Don’t lie. This is you when you’re on evening shift and you can’t cherry pick your way around the L&D orders anymore… (Image)

Steph’s Note: This week, we’re venturing into the oft sideskirted territory of pregnancy and women’s health. Sad, but true. It wasn’t until I had graduated and started working with an internal medicine service that also covered the Labor and Delivery unit that I started learning about the drugs used in this realm. And it was largely self taught because nobody around was really an expert! (I don’t say this to toot my own horn - only to illustrate that you’re not alone if it often feels like the blind leading the blind when it comes to covering L&D orders. But trust me, if you work in a hospital, you will have to verify those long order sets at some point or another. Best to get a jump on understanding what you’re verifying now!)

Here to help us with this is Dr. Joe Nissan, our critical care guru. (If you don’t yet know Joe, you should. Check out some of his previous tl;dr contributions here, here, and here.) Teach us, Joe!

Ok, be honest. Do you avoid women’s health at all costs because treating pregnant patients is freakin’ scary? If you answered yes, then congratulations, you’re like the rest of us. But today, my goal is to expand your obstetric knowledge by exactly one disease state.

Full disclosure. I am NOT a women’s health expert. But I do know a thing or two about preeclampsia/eclampsia.

You’re probably thinking, “Aren’t preeclampsia and eclampsia like the same thing?”

I personally used to use those terms interchangeably. Little did I know that I was wrong. While they indeed share a lot of similarities, preeclampsia and eclampsia have one key difference.

Are you dying to know what this difference is? Keep on reading then…

Let’s Talk About Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a life-threatening condition that affects up to 14% of pregnant women globally, generally during the second half of pregnancy (≥20 weeks), or soon after delivery. In fact, 91% of all antepartum cases develop in the third trimester.

(Image)

Exactly the stress soon-to-be parents need, right?

Common symptoms associated with preeclampsia include hypertension (key feature), proteinuria (key feature), severe headache, blurred vision, vomiting, and sudden swelling of the face, hands, or feet.

Major risk factors for developing preeclampsia/eclampsia include:

History of chronic hypertension

Pregestational diabetes mellitus

Multiple gestations

Pre-pregnancy BMI >30

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Geriatric pregnancy (>35 years old)

Thanks, pregnancy organizations. Thaaaanks.

(Also, if you know what this is from, you will likely be labeled a geriatric pregnancy.) (Image)

Regarding pathophysiology, simply put, it’s complicated. Overall, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is extremely complex and likely multifactorial. And this is tl;dr so we don’t want some super in depth biochemical explanation anyway. So, in the simplest explanation possible, the proposed main tenets in developing preeclampsia suggest:

Abnormal Placentation → Inappropriate Spinal Artery Remodeling → Tissue Hypoxia & Endothelial Damage → Hypertensive Pathology

🙂

Phew. Even the simple explanation is still kind of complex.

Like I said…complicated. (Image)

Anyway, I digress. So how do we diagnose? Pretty simple to be honest. Take a peek at the diagnostic criteria below:

Diagnostic Criteria for Preeclampsia

Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on at least 2 occasions at least 4 hours apart after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive patient AND the new onset of one or more of the following:

Proteinuria ≥0.3 g in a 24-hour urine specimen

Platelet count <100,000/microL

Serum creatinine >1.1 mg/dL or doubling of the creatinine concentration in the absence of other kidney disease

Liver transaminases at least twice the upper limit of the normal concentrations

Pulmonary edema

New-onset and persistent headache not accounted for by the alternative diagnoses and not responding to the usual doses of analgesics

Visual symptoms

So Then, What’s Eclampsia?

I’m so glad you asked! Eclampsia is just like a more severe form of preeclampsia, right?

Eh, kind of…

While preeclampsia and eclampsia share a lot of similarities, they have one key difference. And because I like to summarize everything, look at this beautiful table I made that goes over the clinical differences between mild/moderate preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, and eclampsia.

As you can clearly see, the key difference between preeclampsia and eclampsia is the evidence of convulsive seizures or coma.

Treatment of Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

So far, we’ve talked about the pathophysiology of preeclampsia/eclampsia, diagnostic criteria, and clinical symptoms. Well, how the heck do we treat this obstetric emergency?

Well, if the diagnosis is made, the only definitive treatment is delivery of the baby to prevent development of maternal or fetal complications from disease progression. Delivery leads to eventual resolution of the disease, although end-organ dysfunction may worsen in the first one to three days postpartum.

However, we’re pharmacists. And last I checked, we don’t really help with the delivery of babies. At least I don’t. A little out of my scope of practice. So, what can we do to help stabilize patients in the acute setting?

There are two main goals of care:

Prevent/Treat Seizures

Achieve Adequate Blood Pressure Control

Preventing and Treating Eclamptic Seizures with Magnesium Sulfate

Man, don’t you just love magnesium? It can be used to treat so many different critical disease states. Its numerous mechanisms of actions have shown benefit in the treatment of many disease states including hypomagnesemia, torsades de pointes, status asthmaticus, and even preeclampsia/eclampsia. Pretty freaking cool if you ask me.

Anyway, back to treatment. As we talked about earlier, our number one goal of care is to prevent/treat seizures. This is where magnesium sulfate comes into play. Let’s do a deep dive of everything you need to know about the use of magnesium sulfate.

How does it work?

Magnesium antagonizes the excitatory calcium influx through NMDA receptors, leading to the stabilization of excitable membranes and cessation of seizures. While rapid infusion can lead to vasodilation and hypotension, it is NOT used to help reduce blood pressure.

So please don’t be one of those myth spreaders. Magnesium is NOT used to lower blood pressure in preeclampsia/eclampsia. It is primarily used for its antiepileptic effects.

Ok, now let’s talk about dosing. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the optimal magnesium regimen, when it should be started and terminated, or route of administration as available evidence does NOT support the superiority of a specific approach. Therefore, you may find that your institution uses a different dosing strategy than the one that I will discuss. But in general, a good approach is the following:

IV: 4 to 6 g loading dose over 15 to 30 minutes at onset of labor or induction/cesarean delivery, followed by 1 to 2 g/hour continuous infusion for at least 24 hours after delivery. Maximum infusion rate: 3 g/hour

With that being said, always use your clinical judgment when treating preeclampsia and eclampsia. For example, we are preventing a seizure in patients with preeclampsia. Therefore, a slower infusion of 30 minutes for the magnesium sulfate load is probably ok.

Seizure treatment AND vasodilation?! Hecks to the yes. (Image)

Now let’s flip the script. We will always be treating seizures in patients with eclampsia. So a faster infusion rate for the magnesium load is likely appropriate. Infuse over 15 minutes, if not faster.

This brings us to the next logical question. What even are the risks of rapid magnesium infusion? Primarily hypotension. Considering patients with eclampsia have elevated blood pressure to begin with, some vasodilation isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

And now, the two million-dollar questions that every provider will ask you:

How long should I continue the magnesium drip?

Do I need to follow serum magnesium levels?

To answer the first question. There are NO clear guidelines that specify that exact duration of treatment. Every situation is different and clinical judgment should always be used. However, the ACOG guidelines recommend a continuous infusion of magnesium sulfate for at least 24 hours after delivery.

Now to answer the second question. In patients with normal kidney function, following serum magnesium level is NOT required as long as the patient’s clinical status is closely monitored for signs and symptoms of potential magnesium toxicity and no abnormalities are noted.

Next logical question… What are the common signs of magnesium toxicity? Take a look:

Loss of deep tendon reflexes occurs at 7 to 10 mEq/L

Respiratory paralysis occurs at 10 to 13 mEq/L

Cardiac conduction is altered at >15 mEq/L

Cardiac arrest occurs at >25 mEq/L

So, what other antiepileptics can we give to seizing patients that have a magnesium contraindication or are not responding to magnesium therapy?

That’s always a sucky situation because the ACOG guidelines make it very clear that “magnesium sulfate is more effective than phenytoin, diazepam, or nimodipine.” But we’re left with no choice. Benzodiazepines and/or phenytoin remain the antiepileptics of choice in eclamptic patients who have magnesium-resistant seizures. Common benzodiazepines used include midazolam, lorazepam, and diazepam. Differing institutions may prefer one agent over the other.

Blood Pressure Control in Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

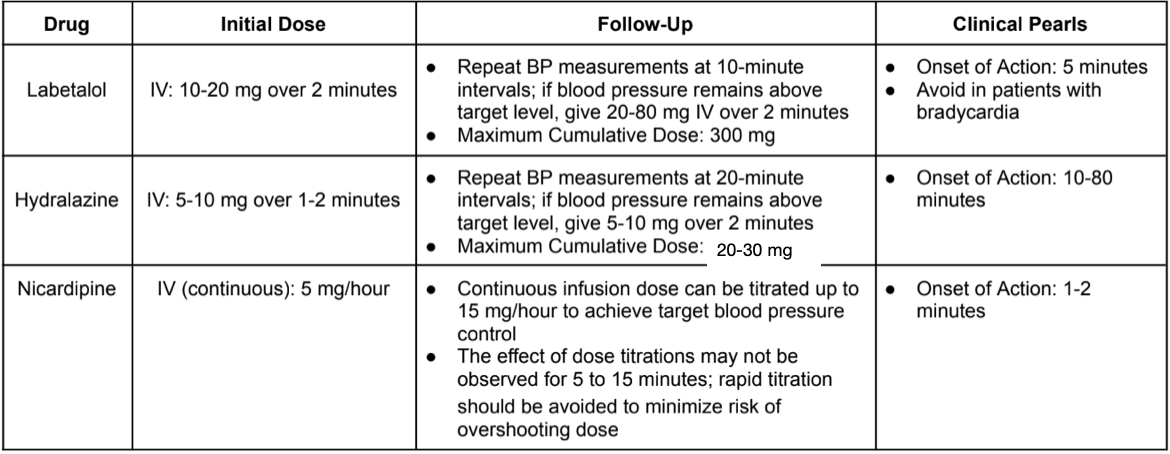

On to our next goal of care, which is achieving adequate blood pressure control. What is our blood pressure goal? The ACOG guidelines recommend a treatment goal of 120-160/80-110 mmHg. Here’s a table that I made that summarizes everything you need to know about achieving adequate blood pressure control in patients with preeclampsia/eclampsia:

The tl;dr of Preeclampsia & Eclampsia

Preeclampsia is a life-threatening condition that may affect pregnant women, generally during the second half of pregnancy (≥20 weeks), or soon after delivery.

Common symptoms associated with preeclampsia include hypertension (key feature), proteinuria (key feature), severe headache, blurred vision, vomiting, and sudden swelling of the face, hands, or feet.

The presence of acute convulsive seizures is the key factor in differentiating eclampsia from preeclampsia.

The 2 main goals of care are to prevent and/or treat seizures and achieve adequate blood pressure control. The only definitive treatment of preeclampsia/eclampsia is delivery. Otherwise, IV magnesium sulfate remains the agent of choice for the prevention/treatment of seizures associated with preeclampsia/eclampsia.

Benzodiazepines and phenytoin may be utilized as second-line antiepileptic options for patients with magnesium sulfate contraindications or treatment resistance.

The ACOG guidelines recommend a blood pressure goal of 120-160/80-110 mmHg. IV labetalol, hydralazine, and nicardipine are safe and effective options that can be utilized to achieve adequate blood pressure control.

There you have it! Preeclampsia and eclampsia in a nutshell. Hopefully you now know enough - to know when you need to investigate further, that is.