The Pharmacist's Crash Course on the Crash Cart

Steph’s Note: This week, we’re back to the clinical life! Per reader request, critical care guru Joe Nissan (last seen on tl;dr here) has cranked out yet another incredibly useful and tl;dr-esque post on the essentials of using a crash cart as a pharmacist. (See, we DO read your emails! We promise :)). If you’ve ever been lost and trying to hide your panic from being the pharmacist in a code blue, we got you. Read this post ASAP. (And for more emergency fun, don’t forget to check out our Acute Medical Emergencies Pocket Guide!)

(Image)

We’ve all been there. You’re staffing at the hospital when all of the sudden you hear a code blue announced overhead on the floor you’re covering. You rush over to the room and crank that crash cart open. You pull out the medication box/tray and stare at the 4 million medications that are in there. You feel slightly overwhelmed and can sense the entire room staring at you.

The physician calls out, “Can I get a dose of epi?” You look for the epinephrine, but there are so many medications. Wait, why are there two different epinephrines? There’s the 1 mg/mL vial, but there’s also the 1 mg/10 mL prefilled syringes. WHY?!?

The nurse comes over to get the meds from you, but you’re not even ready. By now your head is spinning at a million miles an hour, and you’re wishing you paid more attention in that ACLS course you recently took.

We get it, kitty. Sometimes we want to do that too. (Image)

If you haven’t experienced the above scenario, then good for you. You’re smarter and more confident than the rest of us. But, if you have experienced the above feelings of panic and wished you could run from the room, then I come bearing good news.

Here at tl;dr pharmacy, we aim to make complex disease states simple. Today, I am going to give you pharmacist-friendly cardiac arrest algorithms that should hopefully make your life easier. No, this is NOT to replace your ACLS course. You should still get that ACLS certification even if you don’t want to. BUT I am going to give you the realistic expectations of a pharmacist in a code blue.

You, the pharmacist, when some cruel soul singles you out of the crowd to ask at how many Joules to shock the patient. (Image)

Things like how many Joules we shock at or how to read an ECG are great to know. But in the real world, no one’s expecting the pharmacist to differentiate between ventricular fibrillation and pulseless electrical activity on an EKG. And who the heck is going to ask the pharmacist at what Joules we should shock a patient?

So then, what exactly is expected of a pharmacist attending a code blue? I’m so glad you asked.

Pharmacist Responsibilities in a Code Blue

Not to pat ourselves on the back, but pharmacists are capable of doing a lot more than what is normally expected of us. And the same thing applies in a code blue. If you really wanted (or were needed), you can most definitely act as the team leader, provide compressions, read ECGs, prepare medications, etc. However, most of us don’t want those tasks. Just because we CAN doesn’t mean we WANT to. So, realistically, what is actually expected of us in a code blue?

Most pharmacists when faced with the idea of being team leader in a code. It’s bad enough to role play it during ACLS training…let’s not make it reality. (Image)

Medication Preparation - 100% of the time

Drug Information - 100% of the time

Compressions - 5% of the time

Recorder/Documentation - 2.5% of the time

Team Leader - 0.0001% of the time

No, those aren’t proven numbers in some fancy study. But they are pretty realistic. A physician will always be in the room leading the code blue. Nurses will always be in the room to document/administer medications. Nurses/medics/medical students will always be in the room providing compressions and checking for a pulse.

WE (pharmacists) will always be in the room preparing every code blue medication and providing drug information/recommendations. Therefore, this entire post will focus on the cardiac arrest algorithm and crash cart medications. By the end of this article, you should feel a lot more comfortable responding to a code blue.

A Very Brief Overview of Cardiac Arrest (AKA Code Blue)

Simply put, cardiac arrest is the failure of the heart to contract and is evident by the loss of a pulse. No pulse means cardiac arrest, which means dead (sorry, I don’t mean to be so blunt…but it’s true). Our goal is to replenish a pulse and get that heart to beat again (i.e., bring that patient back to life).

Your ACLS course goes super in-depth into the different cardiac arrest rhythm disturbances. However, I am only going to give you the bare minimum information that you will actually need to know from a pharmacist’s perspective. Let’s take a look.

Cardiac arrest rhythm disturbances:

Shockable

Ventricular Fibrillation (Vfib)

Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (pVT)

Non-Shockable

Asystole

Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA)

Again, you realistically do NOT have to differentiate these rhythms on an ECG in a code blue (of course, you can if you want). All you need to know is if the rhythm is shockable or non-shockable. Why? Because they have completely different treatment algorithms that you most definitely need to know as a pharmacist.

For example, let’s say you get called to a code blue. You reach the room, and the physician says, “Patient is in asystole.” Right away, you should remember that asystole is a non-shockable rhythm, and you can start working down the pharmacist-friendly non-shocklable algorithm that we will discuss next.

Pharmacist-Friendly Non-Shockable Rhythm Algorithm (Asystole & PEA)

Yup, that’s literally what you need to know as a pharmacist. That ACLS algorithm guide published by the AHA is great and very inclusive. However, it’s really not necessary for our role.

Again, your responsibility is to be the medication expert on the team. You will have to know what drug, how much, and when to give. And my algorithm here goes over all that :).

Pharmacist-Friendly Shockable Rhythm Algorithm (Vfib & pVT)

Okay, just a small warning. This algorithm is a little more complicated but still much simpler than the AHA algorithm. Let’s take a look.

It looks like a lot. But it really isn’t that bad. Shock twice, give epinephrine, shock again, give amiodarone, lidocaine, or epinephrine.

Rinse and repeat over and over again as long as the patient remains in a shockable rhythm. Just remember, before you give any drug, there should always be a shock beforehand. Not too bad, right?

That Dreadful Crash Cart

We all have a crash cart. And in that crash cart we either have a medication box or a medication tray. In that tray/box, you’ll find tons of medications. A veritable rainbow.

Disclaimer, your institutions’ medication box/tray may slightly differ from mine. But we probably share 90% of the same medications.

Here’s a generic crash cart that I found online:

(Image)

Your medication tray probably looks very similar, right? Well today we’re going to review all of these medications. We’re going to talk about which of these medications are commonly used in a code blue, which are not so commonly used, their indications, clinical pearls, etc. The specific medications we will review include:

Amiodarone

Atropine

Calcium Chloride

Dextrose

Dopamine

Epinephrine

Lidocaine

Magnesium Sulfate

Sodium Bicarbonate

There’s a lot of drugs there. So we’re going to split these meds up into three groups. Commonly used medications in a code blue, somewhat used medications, and not so commonly used medications. It looks a little something like this:

Commonly used medications in a code blue: Amiodarone, Epinephrine, Lidocaine

Somewhat commonly used medications in a code blue: Calcium Chloride, Dextrose, Sodium Bicarbonate

Not so commonly used medications in a code blue: Atropine, Dopamine, Magnesium Sulfate

Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Epinephrine

Concentrations: 1 mg/10 mL prefilled syringe, 1 mg/mL vial

Indication: Sudden cardiac arrest due to asystole, pulseless electrical activity, ventricular fibrillation, or pulseless ventricular tachycardia

Dosing:

IV/IO (preferred routes): 1 mg (using the 0.1 mg/mL solution) every 3 to 5 minutes until return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC)

Endotracheal (alternative route): 2 to 2.5 mg every 3-5 mg until IV/IO access established or ROSC

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

When giving IV/IO, PLEASE always use the 1 mg/10 mL concentration (0.1 mg/mL solution). The prefilled 1 mg/10 mL syringes are great because you never have to question yourself.

However, IF you run out of the prefilled syringes, you can compound a 1 mg/10 mL solution at bedside using the 1 mg/mL vial. How, you ask? Easy. Take the 1 mg/mL vial and add 9 mL of NS to get yourself a 1 mg/10 mL solution. Easy, right?

When giving via the endotracheal route, PLEASE remember to dilute the dose in 5-10 mL NS or sterile water using the 1 mg/mL solution.

Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Amiodarone

Concentration: 50 mg/mL (as a 150 mg/3 mL vial)

Indication: Sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (unresponsive to CPR, defibrillation, and epinephrine)

Dosing:

IV/IO: 300 mg x1, followed by 150 mg x1 (total dose: 450 mg)

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

Please administer amiodarone boluses undiluted when used for cardiac arrest. Sorry to say, the patient is already dead. Their veins aren’t exactly first priority in this scenario, and it will have to be okay if we give it undiluted. Let’s not waste time diluting the drug to avoid vein toxicity. We need this drug in the body STAT.

Your crash cart should NOT have more than 3 vials of amiodarone. If it does, then that’s a possible risk hazard. Look at the dosing again. Two total doses, that's it. 300 mg, then 150 mg, then we’re done. I don’t care if the patient remains in a shockable rhythm. The AHA guidelines recommend a total dose of 450 mg. Each vial is 3 mL of 50 mg/mL for a total of 150 mg per vial. Therefore, for the first dose, you’ll draw up two vials (300 mg). The second dose is one vial (150 mg). And that’s it.

(Now if the patient responds to amiodarone and you achieve ROSC, it’s possible the provider may want to continue amiodarone as an infusion. If so, you enter the order, call the IV room, and ask them to make a bag STAT. This continuation infusion should not come from your crash cart.)

Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Lidocaine

Concentration: Lidocaine 2% 100 mg/5 mL prefilled syringe

Indication: Sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (unresponsive to CPR, defibrillation, and epinephrine)

Dosing:

IV/IO: 1 to 1.5 mg/kg; repeat with 0.5 mg to 0.75 mg/kg every 5 to 10 minutes as necessary (maximum cumulative dose: 3 mg/kg or up to 300 mg within 1 hour)

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

There’s a lot to discuss here. Yes, the dosing for lidocaine is weight based, and who has time to be doing math in a code blue? BUT we’re in luck. It’s a large range. Most of our patients are between 70 and 100 kg, right? Therefore, anyone within that weight range can just get the full 100 mg prefilled syringe. And then for the next dose, just give 50 mg. Again, it’s within that dosing range. Remembering this will make your life much easier. Just make sure your patient is between 70-100 kg.

Make sure you remember to NOT surpass that maximum dose within the first hour. Very very very very rarely will the team code someone for more than an hour. So 99% of the time, just remember that you cannot exceed 3 mg/kg or 300 mg per hour. If you reach that max and your patient remains in a shockable rhythm, then it’s time to switch over to amiodarone or epinephrine.

Somewhat Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Calcium Chloride

Concentration: 10% Calcium chloride 1 g/10 mL prefilled syringe

Indication: Cardiac arrest or cardiotoxicity in the presence of hypocalcemia or hypermagnesemia/hyperkalemia

Dosing:

IV/IO: 500 to 1000 mg as a rapid bolus; may repeat as necessary

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

Let’s look at that indication again. It is ONLY to be used for patients in cardiac arrest with proven/suspected hypocalcemia or hypermagnesemia/hyperkalemia. There is very conflicting data on the benefits of calcium chloride in cardiac arrest.

Per the AHA guidelines, routine use in cardiac arrest is NOT recommended due to the lack of improved sustained ROSC and the lack of improved survival. So please, don’t give calcium chloride to ALL cardiac arrest patients. ONLY those with concerns for hypocalcemia, hypermagnesemia, or hyperkalemia.

Yes, generally we need a central line for calcium chloride administration due to the risk of extravasation and vein toxicity. HOWEVER, in cardiac arrest, our goal is bring these patients back to life. Meaning we need to give drugs ASAP in whatever line we have. We do not have time to get a central line in place. So please, just give calcium chloride in whatever IV line you have. The benefits most definitely outweigh the risks in these patients.

If giving sodium bicarbonate and calcium chloride together, remember to flush the line TWICE with 10 mL of NS in between drug administration to prevent any precipitation.

Somewhat Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Dextrose

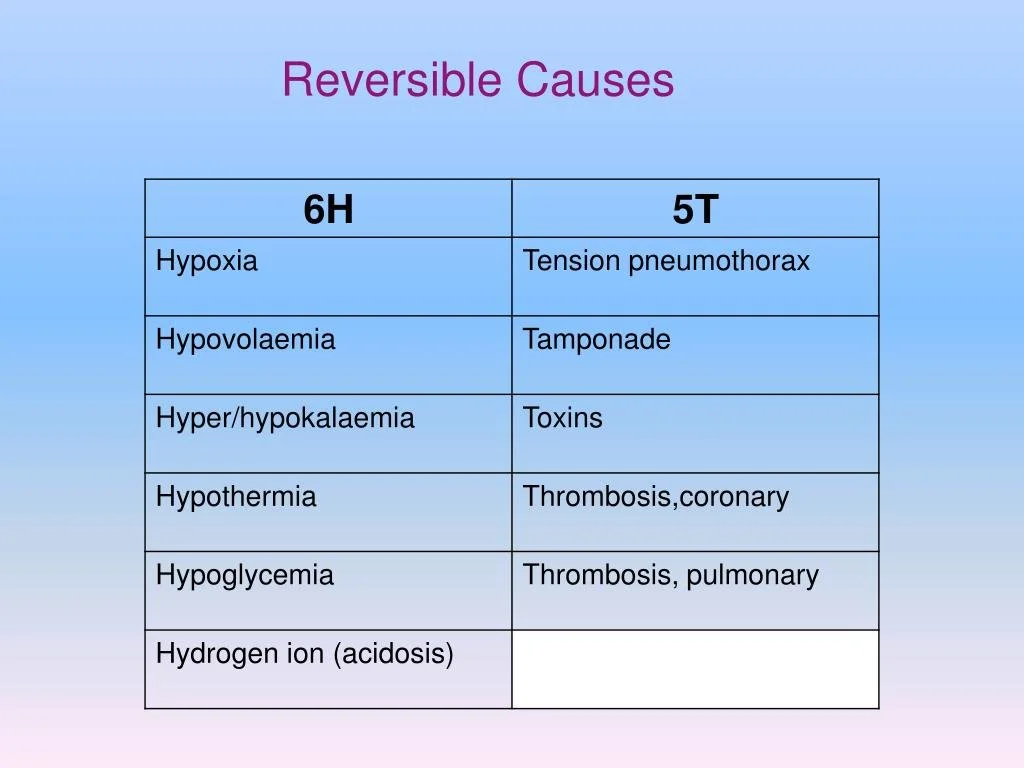

A quick refresher on the H’s & T’s of cardiac arrest. (Image)

Concentration: 50% Dextrose 25 g/50 mL prefilled syringe

Indication: Cardiac arrest in the presence of hypoglycemia

Dosing:

IV/IO: 25 g (50 mL D50W) as a rapid bolus; may repeat as necessary

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

Dextrose is the most straightforward. One of our H’s & T’s in cardiac arrest is hypoglycemia. Yes, having super low blood sugar can cause cardiac arrest. Therefore, correcting that blood sugar can potentially resolve cardiac arrest. Other that that, you should NOT be giving out D50W to everyone with cardiac arrest.

Somewhat Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Sodium Bicarbonate

Concentration: 8.4% Sodium Bicarbonate 50 mEq/50 mL prefilled syringe

Indication: Prolonged cardiac arrest in the presence of metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, or sodium channel blocker (e.g., tricyclic antidepressant) overdose

Dosing:

IV/IO: 1 mEq/kg/dose once; repeat doses should be guided by arterial blood gases or serum bicarbonate concentration

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

I literally wrote an entire post about how we should NOT routinely give sodium bicarbonate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to increased risk for worsened neurological outcomes and decreased rates of sustained ROSC. So check that out if you haven’t already.

I know I am a sodium bicarb hater, but it does have a role in specific scenarios. While the AHA does NOT recommend the routine use of sodium bicarbonate for cardiac arrest, its use may be appropriate in patients with metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, or sodium channel blocker overdose.

If giving sodium bicarbonate and calcium chloride together, remember to flush the line TWICE with 10 mL of NS in between drug administration to prevent any precipitation.

Not So Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Atropine

Concentration: 1 mg/10 mL prefilled syringe

Indication: Symptomatic and/or hemodynamically unstable bradycardia

Dosing:

IV/IO/IM (preferred routes): 1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes as needed until symptoms resolve or heart rate is stabilized (maximum total dose: 3 mg)

Endotracheal (alternative route): 2 to 2.5 mg every 3 to 5 minutes

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

Okay so this is our first NOT so commonly used medication in code blue. There pretty much is NO role for atropine in someone with cardiac arrest. It’s primarily in the crash cart to prevent cardiac arrest in someone who is rapidly decompensating and has unstable bradycardia.

So you’re really only trialing atropine in someone who HAS a pulse but is on the cusp of developing cardiac arrest if the heart rate is not increased rapidly. BUT, if that same patent develops cardiac arrest, get rid of that atropine, and start with the other medications we talked about in our algorithms.

Not So Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Dopamine

Concentration: 400 mg/250 mL premixed bag

Indication: Symptomatic and/or hemodynamically unstable bradycardia/cardiogenic shock (unresponsive to atropine)

Dosing:

IV (continuous infusion): 5 mcg/kg/min; increase dose every 2 minutes until desired effect (maximum dose: 20 mcg/kg/min)

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

I really have no idea why our crash carts keep carrying dopamine premix bags. Just like atropine, dopamine has NO role for patients in cardiac arrest. It’s in the crash cart as a critical medication to help prevent cardiac arrest in someone who is rapidly decompensating and has unstable bradycardia/cardiogenic shock. If dopamine is used, it generally is used before cardiac arrest or after ROSC is achieved.

For example, let’s say you have a patient with cardiac arrest. You achieve ROSC and cycle their hemodynamics which shows bradycardia and/or hypotension. You can then start a dopamine drip for inotropic/vasopressor effects to improve their hemodynamics and hopefully prevent them from going back into cardiac arrest. But if a patient is currently in cardiac arrest, please do NOT start a dopamine drip. Stick to the drugs highlighted in the cardiac arrest algorithms above.

Not So Commonly Used Medications in Code Blue - Magnesium Sulfate

Concentration: 1 g/2 mL vial

Indication: Ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia associated with torsades de pointes

Dosing:

IV/IO: 2 g administered as a bolus over ≥1 to 2 minutes; if ineffective, may repeat immediately with 2 additional 2 g bolus doses as needed (maximum total dose: 6 g)

Tl;dr Clinical Pearls:

Please don’t forget to dilute the 2 g dose with 10 mL of D5W. Again, you’re diluting with 10 mL of D5W.

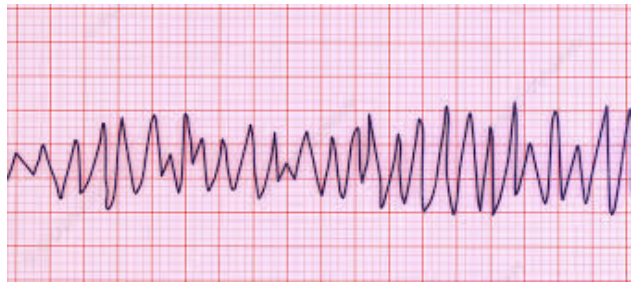

If you don’t remember what torsades de pointes looks like on an ECG, here’s a picture:

Remember, “torsades de pointes” translates to “twisting of the points.” It helps me to remember it because it looks kinda like a DNA helix twisting around. (Image)

A Few Other Survival Tips for Using the Crash Cart

Now that we’ve discussed the need-to-know-info on the crash cart medications, here are a couple other thoughts that might help you survive your code blue experiences (and therefore, perhaps, help your patients survive :)).

Take a page out of their book… always be prepared. (Image)

First, yes, we are pharmacists, and we’re technically in charge of the medication box/tray of the crash cart. But that doesn’t mean that people aren’t ever going to ask you to pull anything else out of that cart. GET FAMILIAR with the other drawers and what’s where. I can guarantee at some time or another, you will need to pull flushes, needles (to make dilutions, etc), fluid bags, the arterial blood gas kit (that’s always a tricky one to find!), the pressure bag for fluids, and heck, even the AMBU bag. So please please please know where things are in the crash cart.

Second, if you can, have a lifeline. For some, it’s a peripheral brain in their pocket with the ACLS algorithms or the drugs, doses, and how they’re administered. You think you know this stuff…until the time comes and you’re feeling the pressure. Especially if you don’t do codes every day. There is absolutely no shame in having a reference on hand, just in case.

For others, that lifeline means calling for a backup pharmacist (if available). Having an extra set of pharmacy hands outside the room can be a huge help if you need something from the Pyxis machine on the unit or something from the tube station sent from the IV room. You have no idea how many times the crash cart gets shoved to the back of the patient’s room, and therefore, YOU are in the back of the room. And trying to navigate your way out can be hazardous. To everyone.

Although most places are trying to get better at thinning the rooms out to essential personnel during a code, sometimes it still can feel like this. (Image)

(Just ask Steph, who as a resident way back in the day in the ER, tripped on the lead wires connecting the patient to the Zoll machine when trying to get out to the Pyxis machine for a paralytic. No, they did NOT disconnect, hallelujah! But just saying, check your surroundings when you get shoved in the corner. Or better yet, try not to get shoved in the corner. Move the crash cart to a better location before the room fills up with every medical resident in the entire hospital.)

Third, try to stay up on your institution’s drug shortages and what changes are being made to the crash cart. For a few years there, it seemed like everything in the medication tray was short! We were creating epinephrine syringe kits to make doses from the 1mg/mL vial. We were doing the same thing with sodium bicarbonate vials. We had glass ampules of epinephrine at one point as well, so we had to make sure to use filter needles when drawing up those doses. You just never know! But it sure does help to have an idea of what changes are being made to the crash cart medication tray before you’re in a code, panicking that you don’t see the nice, easy prefilled syringes that you learned in ACLS.

The tl;dr of Crash Carts for Pharmacists

And that, folks, is a wrap. Remember, your crash cart medications may slightly differ than mine. You may have a few more medications or a few less. And that’s okay. But overall, we should share a lot of the medications discussed in this post. You can always go above and beyond when it comes to ACLS. The more you know, the better. But hopefully, this post scrapes the minimum that you need to know to get through a code blue as a pharmacist.

Make sure you can always differentiate between shockable and non-shockable rhythms, and the rest is easy!