What Every Pharmacist Should Know about Enteral Nutrition and Medications

Steph’s Note: This week, we welcome back a previous poster who took us deep into the brain with his primer on status epilepticus. This time, Dr. David Mastro is taking us down the path of nutrition. But wait…we’re pharmacists. We manage the meds, right? Why are we talking about food and access points and flushing, oh my?

Guess what, my phriends… Pharmacists often do nutrition too! And just like you have to counsel your patients at the counter or at discharge not to take that quinolone with their multivitamin or calcium supplements, pharmacists have to pay attention to drug-nutrient interactions. And you thought the scope of pharmacists couldn’t get any wider…surprise! Take it away, David!

Today we are going to talk about the importance of food. Well, in more academic terms… nutrition. Yes, it sounds self-explanatory, but as pharmacists, it is important to understand the comprehensive therapy that is nutrition support (NS). Pharmacists in the hospital setting are commonly involved in providing NS therapy, so it is important to understand what goes into providing these services.

There are two types of NS provision: enteral nutrition (EN) and parenteral nutrition (PN). Each type is vast, so we will focus on EN today! Keep an eye out for a possible part 2 covering PN, and you can also check out this previous tl;dr post if you want to go ahead and get your feet wet.

Before we dive into the indications, safe practices, and complications of EN, it is important to briefly touch on malnutrition. Malnutrition is common amongst hospitalized patients, although underdiagnosed. Roughly 30-50% of hospital patients are malnourished or are at high risk of malnutrition. Although different definitions exist, malnutrition can be defined as an acute, subacute, or chronic state of varying degrees of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammation. The result is a change in body composition and reduced function.

In undernutrition, which is commonly what EN aims to treat or prevent, physiologic changes show as weight loss, depletion of body fat, and depletion of muscle mass. In the hospital setting, malnourishment leads to worsened outcomes, including increased length of stay, impaired wound healing, and increased mortality.

I will say that again… increased mortality is an adverse outcome associated with malnourishment. Hopefully that can convince you of the important of this topic,

This kid knows how to do messy nutrition in a goooooood way lol (Image)

Now let us have some fun with our food (not in a messy way though)!

What is Enteral Nutrition (EN)?

Enteral nutrition (EN) is defined as the delivery of nutrients directly to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by tube, bypassing the oral cavity. Also, you will commonly hear healthcare professionals refer to enteral nutrition as tube feeding, so just be aware that the terms EN and tube feeding can be used interchangeably.

There are a variety of factors that must be taken into account when deciding to initiate EN or not. But…the most important question we ask ourselves is this: is the GI tract functional? You have probably heard this so many times throughout your pharmacy school training, but here it is again.

If the gut works, use it.

There are so many important gut barrier defense functions that are maintained when the GI tract is being fed. I hope I am contributing to the deep-seated spot in your brain that is storing that knowledge, sorry not sorry.

So…patients without (or expected to be without) adequate oral intake for a prolonged period (usually 5-7 days) who have a functional GI tract are indicated for EN. Oral intake may be impossible (e.g., intubated, unable to swallow due to disease such as stroke), inadequate (cachexia, high metabolic demand from critical illness), or unsafe (altered mental status), and thus EN is indicated.

When can we NOT use EN?

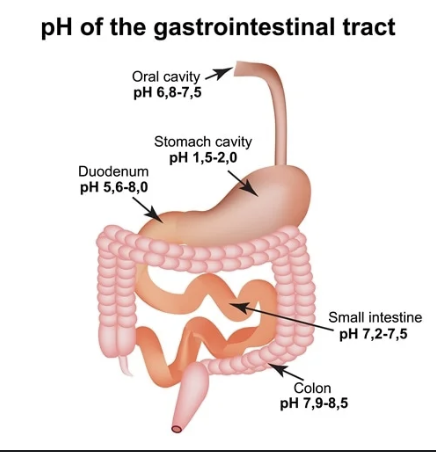

Sometimes, unfortunately, we cannot safely run tube feedings. This is usually due to some functional or structural abnormalities occurring with the GI tract. The American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) has listed some relative and absolute contraindications to EN. See the table to the left.

Here is something more to think about - we can actually feed beyond the stomach. Let’s take a moment to explore this idea further by considering the various access points for EN. There are 3 main access sites for EN:

The nose

The stomach

The jejunum

(Image)

For the first option, when inserting a tube into the GI tract via the nasal passage, it can terminate in the stomach, the duodenum, or the jejunum. So you can feed the stomach or the small intestine from the nose. These tubes are relatively small in diameter (as you would expect because otherwise…ouch…). You will often hear nasogastric tubes referred to as Dobhoff tubes, although Dobhoff is really a specific type of small-bore, flexible nasogastric tube.

Speaking of size, tube diameter is measured according to the French system. Nope, you don’t have to say the number sounding like the Pink Panther, although that would be highly entertaining on rounds. Rather, the French gauge system is one French increment equals 0.33 millimeter. So adults usually have small bore nasal access tubes that measure 8-12 Fr in diameter, about 2.64-3.96 millimeters.

In contrast, gastrostomy tubes (inserted directly into the stomach) and jejunostomy tubes (inserted directly into the jejunum) are larger in diameter. For example, G-tubes, often of the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or PEG variety, are usually 18-24 Fr.

Now that we’ve established how it’s possible to feed beyond the stomach, those with gastric outlet obstruction are not considered contraindicated (so do not confuse bowel obstruction with gastric outlet obstruction). Also, it is safe to initiate EN in pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and GERD, which I have included here because some clinicians feel it is standard to withhold EN in pancreatitis. (I am totally not being influenced by personal experience when I say that… okay… maybe a little bit.)

Now take a break to reflect so far, and then continue reading as we have lots more to talk about.

Medication Delivery and Safe Practices with Enteral Nutrition

Now onto what we should all be experts in (hear my sarcasm): drug and EN interactions!

Although this is an area with relatively limited robust research, there are some significant interactions that pharmacists should be monitoring for. Clinical pharmacists have an important role to ensure the safe administration of medications via enteral feeding tubes in patients who are receiving EN. Interactions between drugs and enteral feeds may lead to reduced absorption of the drug or blockage of the feeding tube.

No bueno. Then there’s a lot of work either to try to unclog the tube (often with a mixture of pancreatic enzymes and sodium bicarbonate) or, as a last resort, replace the tube.

Diarrhea is the most commonly reported complication (50%) amongst patients receiving medications via enteral access tubes, which can further reduce absorption. Clogging of tubes is an issue with administration of medication via enteral feeding tubes 15% of the time, and the risk is higher with the use of small-bore (5-12 Fr) nasoenteric tubes. It is recommended to use at least use a 10 Fr tube size if medication administration is planned.

It’s also essential for pharmacists to consider where particular medications are absorbed and whether a patient is actually getting what they are being administered per tube. This can get interesting since we don’t always have all the pharmacokinetic data available for every drug, but keep reading to learn some common highlights.

What drugs should not be administered into the small intestine?

We should first highlight some medications that should not be administered via feeding tubes that terminate beyond the stomach in the small intestine (e.g., nasoduodenal, nasojejunal, jejunostomy). These include medications such as antacids (Maalox, Mylanta, Gaviscon, Peptac, Mucogel) and sucralfate, which have minimal efficacy in the small intestine and also increase the risk of blockage when combined with protein in EN formulations.

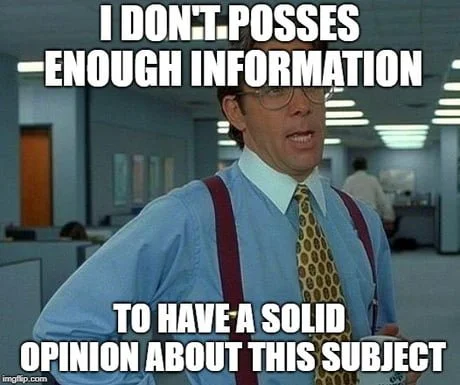

Note how the pH increases significantly from the stomach to the duodenum and steadily rises from there when traveling through the small and large intestines. (Image)

Antifungal wise, ketoconazole and itraconazole require acidic environments for maximal absorption, so the small intestine is not ideal for absorbing a sufficient dose. (Check out the image to the right for a reminder of GI tract pH variations.) On the other hand, fluconazole may actually experience increased absorption in the small intestine and thus put patients at an increased risk of toxicity. Other drugs with increased absorption post-pylorically include ciprofloxacin, azathioprine, zinc, and pravastatin.

Similar to ketoconazole and itraconazole, there are a number of medications with decreased absorption if administered beyond the stomach. These include allopurinol, baclofen, gabapentin, and sirolimus.

Lastly, aspirin and ferrous sulfate (oral iron preparations) require gastric acid for dissolution and subsequent absorption in the duodenum. There is a lack of data on the clinical significance of the absorption considerations with the drugs just mentioned, but it is probably best practice to ensure gastric administration of these medications, if possible.

How it feels when you’re researching whether your patient with an NJ tube is actually absorbing and deriving benefit from their medications… (And yes, I know “possess” is missing an s, which hurts my soul, but the meme is the meme.) (Image)

So, in case you hadn’t noticed from this little taste of the topic, solving clinical issues related to enteral medication administration or ensuring the most appropriate provision of nutrient and pharmacologic therapy can be challenging. It is an undertaught topic in pharmacy school, and I urge you all to do your own research and use the various resources available to you to answer questions and solve issues about specific drugs. Sometimes, however, you kind of just have to manage based on clinical effects if you can’t find the exact answers you’re after in the literature (nerve wracking, I know).

With that said, I want to list a few additional particular interactions to look out for when reviewing the safety and efficacy of drug and enteral nutrition therapy in tube-fed patients.

Phenytoin: There are many case reports and low-quality cohort studies suggesting an increased risk of subtherapeutic effects (i.e., seizures) when oral phenytoin is administered alongside continuous enteral feeds. However, newer evidence from randomized controlled trials shows no difference in phenytoin bioavailability with or without EN. Therefore, it is not necessary to hold tube feedings for 2 hours before and after phenytoin administration. However, the suspension should be diluted (1:1) before flushing.

The same goes for carbamazepine, which actually doesn’t require holding tube feedings for 2 hours before and after administration. Nonetheless, obtaining drug levels in these patients may not be a bad idea to ensure appropriate therapy.

Warfarin: If you work in a hospital setting, you should prepare yourself for questions about warfarin. I would bet (although I don’t recommend gambling) you will be asked by nurses many times over if warfarin can be crushed. Historical concerns focused on reported treatment failures in warfarin patients receiving EN, which were attributed to the high vitamin K content in feeds.

In more recent times, however, the vitamin K content in formulas has been restricted significantly. Nonetheless, treatment failures have still been reported, suggesting that the warfarin/EN interaction goes beyond the vitamin K content. Therefore, it is best to separate EN administration by at least 1 hour before and after warfarin administration. This showed an improved INR response in a crossover case series.

Levodopa (Sinemet/Madopar): Where are my gym-going, iron-pumping, metal-moving weight-lifters at? This next interaction should sit close to your heart because it’s all about the protein! The protein in enteral feed formula competes for intestinal absorption with levodopa, which can ultimately lead to reduced bioavailability and an increased risk in Parkinson’s Disease flares in acutely ill patients.

Preventing this harmful interaction may require separating levodopa administration from intermittent protein/EN by at least 2 hours, with breaks in feeding being consistent. But have you ever seen the dosing on levodopa in a severe Parkinson’s patient? Sometimes it’s 10 - yes, TEN - times a day! So how do you logistically separate each dose from EN by 2 hours…yeah, I don’t know either.

So another option is to restrict levodopa exposure to daytime hours, and run continuous EN at night. However, it is preferred to empirically increase the levodopa dose rather than restrict daily protein supplementation or shift its administration in the evening. This just increases the risk of not meeting daily protein requirements, and we don’t want that now do we.

Fluoroquinolones: Cations such as magnesium, iron, and calcium are present in higher concentrations in enteral feed compared to regular diet. The fluoroquinolones, a drug class that I despise (or shall I simply say do not like), bind to these ions and form insoluble chelates, resulting in decreased bioavailability. It is best to separate administration of enterally administered fluoroquinolones by at least 2 hours before and after drug administration.

Other medication/medication classes with drug-nutrient interaction considerations include bisphosphonates, digoxin, rifampin, isoniazid, voriconazole, and dolutegravir. Use of these medications via feeding tubes may require a break in feeding and closer monitoring. Luckily for you and me, however, many drug-nutrient interactions not named in this article are not clinically relevant in the average hospitalized patient since their impact develops gradually over time (and hopefully that hospitalized patient will be done with enteral nutrition by the time the interaction would manifest).

Recommendations for Drug Administration via Feeding Tubes

Solid medications are commonly crushed (i.e., tablets) or opened (i.e., capsules) in order to administer via a nasogastric, nasoduodenal, nasojejunal, jejunostomy, or gastrostomy tube. However, solid dosage forms are to be avoided if opening or crushing would result in significant change to the absorption profile of the medication.

Therefore, it is best practice to limit enteral medication administration to immediate-release tablets and dry content capsules (this just means capsules that can be emptied of a dry, fine powder). Modified-release products, such enteric coated and sustained-release products, should be avoided.

Nursing staff should be educated on the flush-administer drug-flush protocol, where the tube is flushed with 15-30 mL of water (ideally purified, but can use tap water) before and after each individual medication administration.

Liquid dosage formulations are preferred when available. However, around 50% of patients receiving EN and liquid medication through feeding tubes experience diarrhea. We will talk more about diarrhea (I know… everyone’s favorite topic) later, but it should be noted that many EN patients receiving enterally administered liquid medication may have diarrhea due to the adjuvants and ingredients in the liquid formulation and not the EN formula itself. If this is recognized, it may prevent unnecessary switching of the EN formula.

Sorbitol-containing medications are commonly at fault. I am being nice so here are some examples of liquid medications with significant sorbitol content: acetaminophen, sodium polystyrene sulfonate suspension (SPS), furosemide, amantadine, calcium carbonate, lithium citrate, guaifenesin/dextromethorphan, nortriptyline, penicillin V potassium, and metoclopramide. These are some drugs to look out for when assessing EN intolerance (more to come on EN intolerance).

I almost forgot to mention, it is generally recommended to dilute viscous liquid solutions and suspensions in a 1:1 ratio to lower the osmolality. This enhances the delivery of drug and reduces the risk of an osmotic effect and subsequent localized adverse effects. If I am being honest, more data is necessary to assess the appropriateness of medication dilution. Nonetheless, phenytoin suspension, carbamazepine suspension, azithromycin suspension, and levofloxacin suspension all have good data supporting their dilution (1:1) before flushing down a tube.

As pharmacists we should take initiative to evaluate the enteral administration of solid and liquid dosage formulations. Our recommendations are important, and it is our role to educate nurses on proper medication administration if we believe therapy may be compromised by suboptimal practices. In general, no medication should be added directly the enteral feed!

Complications Associated with Enteral Nutrition

Refeeding Syndrome

Refeeding syndrome (RS) is a collection of metabolic complications associated with starting nutrition in a malnourished patient. Electrolyte abnormalities, fluid retention, sodium retention, hyperglycemia, fluid overload, and thiamine deficiency are common. Historically, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) has been considered a strong risk factor for RS, but it is important to recognize that this life-threatening complication can occur regardless of the source of nutrition- like in EN.

The incidence of RS is highest in critically ill patients with little to no nutritional intake for 5-7 days. Okay, for now I will bite my tongue because we can always talk more in a possible part 2 covering PN. But… I wanted to provide a neat chart from ASPEN on how to recognize patients who are at moderate and high risk of RS. Other patient factors that may predispose someone to RS include underlying malignancy, chronic alcoholism, malabsorptive state, history of anorexia nervosa, bariatric surgery history, and more.

Yoda understands refeeding syndrome (but apparently not grammar…it’s slow-LY, Yoda…). (Image)

In general, most guidelines recommend to avoid an initial caloric provision of more than 10 g/kg/day (at most 20) in patients at moderate risk of RS and 5 g/kg/day in those at high risk. Feeding advancement in these patients should occur slowly (33% every day) toward goal over 4-7 days. Other than limiting aggressive nutrient provision, your astute pharmacist mind should think about thiamine supplementation and electrolyte replacement.

Thiamine is your friend and an important component of normal energy metabolism and glycolysis. It is recommended to provide 100 mg thiamine for 5-7 days in these patients. As for electrolyte replacement, magnesium, phosphorous, and potassium should be replaced before EN initiation and as needed after.

GI Complications of Enteral Nutrition

Almost 1 in 3 patients receiving good ole tube feeds experience intolerance, which is used synonymously with complications. It is relevant to discuss interventions for aspiration and select GI complications (gastroparesis and diarrhea).

Gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying: Critically ill patients are predisposed to gastroparesis due to abnormal gastric motility in the setting of serious illness. This reduced gastric emptying may also lead to nausea/vomiting. Options to address gastroparesis include minimizing exposure to opioid drugs and catecholamine-derivatives, reducing the feeding volume/rate, utilizing a formula with less fiber and fat content (more to come on this), and adding a prokinetic agent such as metoclopramide.

No truer book twas ever written. (Image)

Diarrhea/constipation: Time to talk poop! I probably shouldn’t have used an exclamation point at the end of that sentence, but this is still an exciting topic because diarrhea is the most common GI complication in EN patients (so knowing how to respond is crucial for nutrition support pharmacists).

Diarrhea in the tube fed patient can be due to many factors, so in general, effort should be aimed at identifying and correcting the most likely underlying cause. We can loosely define diarrhea as greater than 500 mL of liquid stool/day or more than 3 liquid stools/day for 2 or more consecutive days. Tube feeding-related risk factors include too rapid delivery or advancement of formula, an intolerance to the formula composition, administration of large volumes of feeding into the small bowel, and formula contamination.

If diarrhea occurs with a fiber-free formulation, switching to a fiber-containing formulation or using a supplement can be considered. Furthermore, consider switching to a formulation lower in fat if a high-fat formulation is being used (see more specifics on formulation below). Pharmacotherapy with loperamide (2 mg every 3 hours, maximum daily dosage of 16 mg) or diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil) can be considered later line and are generally safe to use in these patients.

Aspiration: Aspiration pneumonia (secondary to inhalation of enteral feeds) is probably the most serious complication associated with tube feeding. In critically ill patients, placing the feeding tube lower in the GI tract is preferred as there is a lower risk of aspiration. This means utilizing jejunostomy tubes and avoiding terminating tubing in the stomach. Along with other general precautionary measures, post-pyloric feeding is less likely to result in aspiration pneumonia and generally allows for increased nutrient delivery.

Monitoring: Patients should be evaluated daily for intolerance of EN. This includes monitoring for nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, bloating, cramping, and diarrhea/constipation. Intolerance is likely to develop within 1-3 days of initiation of tube feedings. Gastric residual volume (GRV) is the volume of contents in the stomach. These GRVs have been historically used to monitor intolerance and identify patients at risk for vomiting, aspiration, and/or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

However, current guidelines DO NOT recommend the routine use of GRV alone to assess tolerance to EN. In the ICU, GRVs less than 500 mL have been deemed to be clinically insignificant and should not warrant the discontinuation of tube feedings in patients without signs and symptoms of intolerance. Basically, GRVs should only lead to a decision to reduce the rate of feeding or stop feeding if the GRV is greater than 500 mL AND the patient is symptomatic. However, as already stated, obtaining these measurements should not be routine as they don’t prevent further morbidity in the absence of intolerance symptoms.

And exhale… I hope I inspire you to discourage routine GRV measurements.

Choosing an Enteral Nutrition Formula

There are a variety of formulas to choose from. If you don’t mind (which I assume you must not, especially if you are still reading this article at this point… thank you by the way), I would like to list the different categories and commercial brands. As you will see, there are different disease states that may make one formulation more desirable over the others. Different hospitals are likely to have different brands of enteral feed formulations available to select by providers, but the broad categories are listed below. I have also included the products that are available at my institution for illustrative purposes.

Polymeric: Many commercially available feeding formulations (e.g., Jevity) fall under the standard polymeric category. Most patients can meet their nutritional needs with these formulations, which are composed of intact nutrients in a balanced mix of carbohydrates, fat, and protein.

These formulas generally provide between 1-1.2 kcal/mL and usually include more dietary fiber than other formulation categories. These formulas usually have insoluble fiber and should therefore generally be avoided in critically ill patients and those with gastric motility dysfunction. However, since fiber should be incorporated in patients receiving long-term EN, polymeric formulations are suitable for long-term feeding.

Semi-elemental/elemental: These formulations are also sometimes referred to as “defined” diets or peptide-based. Products in this category contain protein and/or fat components that are hydrolyzed into smaller, more digestible parts (i.e., free amino acids). These traditionally contain higher proportions of protein in the form of free amino acids, dipeptides, or tripeptides, and a low amount of fat. These formulas find use in critically ill patients, specifically in those who may not tolerate a standard, intact formulation (e.g., high output fistula patients).

Furthermore, these may be recommended in patients with severe pancreatic insufficiency such as acute and chronic pancreatitis, and cystic fibrosis. Patients with short bowel syndrome may also tolerate elemental formulas better than others.

Disease-specific: Okay, last but not least! Disease-specific formulations exist to meet unique metabolic requirements associated with specific disease states. On my institution’s formulary, we have OSMOLITE, PIVOT, Nepro, and GLUCERNA. To give you an idea of how these products are formulated for specific disease states, PIVOT is an immune-modulating formula containing glutamine and arginine because of their potential role in supporting the immune response and promoting tissue repair. Immune-modulating formulations should be considered in TBI, surgical, and trauma patients, but should NOT be used in those with sepsis.

In diabetes mellitus, GLUCERNA offers a unique carbohydrate blend to minimize the risk of uncontrolled hyperglycemia. A renal-specific formulation available at my institution is Nepro. This is a caloric-dense formula with a low electrolyte count designed to meet nutritional needs with lower volume. Although not always the best choice for a patient with renal dysfunction, this can be considered in someone with persistent electrolyte abnormalities. Nepro may also be a choice for patients requiring dialysis who need more protein.

Lastly, OSMOLITE is a fiber-free formulation that may be useful in patients with anatomical abnormalities at risk of fiber intolerance. Less fiber is generally better in patients with severe sepsis or cardiogenic shock, so OSMOLITE may be considered in these patients as well. So, in case that was a question of yours… you can use EN in septic patients (just not immune-modulating products).

The tl;dr of Enteral Nutrition for Pharmacists

EN is often overlooked but is crucial to prevent increased morbidity and mortality in patients who are either malnourished or at risk of malnourishment, especially in the hospital setting. In patients without a small bowel obstruction (SBO), GI bleed, or ischemic bowel disease who cannot maintain adequate oral intake, EN is indicated. In critically ill patients, ASPEN recommends EN to be initiated within 24-48 hours, with the goal of meeting >75-80% of energy needs within the first 48-72 hours of ICU admission.

As pharmacists or pharmacists-in-training, unique to our perspective, we may commonly find ourselves managing the safe and effective administration of medications via feeding tubes. When administering solid dosage forms, it is best to avoid modified-release formulations and stick to immediate release tablets and dry content capsules. Research on medication administration via feeding tubes is limited, but there are some medications to put on your watch list. Nonetheless, medications should be administered down tubes one by one and with flushing of 15-30 mL before and after their administration.

Monitoring of intolerance to EN and management of complications is another area of care where pharmacists can find a role. Gastroparesis, diarrhea, and aspiration are the main complications of EN, each with various prevention and management strategies. Terminating feeding tubes beyond the stomach may reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Evaluate patients daily for nausea, abdominal distention, bloating, gas, and loose bowel movements to help identify necessary interventions.

Lastly, EN formulation choice may be disease-specific, but its important to start tube feedings at a low rate (i.e., 20 cc/hr) with gradual advancement.

And there you have it! Now you’re ready to expand your pharmacy purview into the world of nutrition - happy learning!