Complications of Cirrhosis: Part 2

Steph’s Note: In Part 1 of Cirrhosis, we covered a lot of anatomy and pathophysiology. We chatted about ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. It was a thick post, not gonna lie. If you haven’t read it yet, you should definitely detour over to Part 1 first and then come back over here to Part 2.

In this section, we’re going to continue on with a few more complications of cirrhosis, so get ready for more dedicated liver time!

We combined ALL of the posts in this Liver series AND our Kidney series into a single PDF. If you’d like a downloadable (and printer-friendly) version of this article, you can get one here

Cirrhosis Complication #3: Hepatic Encephalopathy

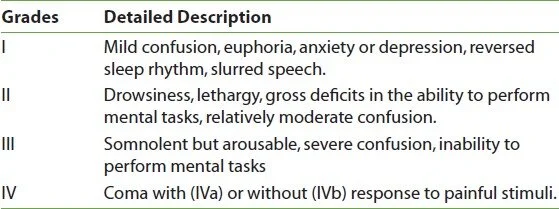

This is pretty much what the name sounds like - altered mental status secondary to hepatic insufficiency. It’s estimated that 30-45% of patients with cirrhosis develop HE. It can have a significant impact on healthcare utilization (an estimated $1-7 billion/year due to hospitalizations) and quality of life for patients. HE exists on a spectrum of symptoms, and severity is graded according to the below system:

It’s not entirely clear whether this encephalopathy is due to the build up of one particular toxin in the setting of altered hepatic clearance or whether it’s the culmination of one’s liver not doing its normal filtration processes.

Is that ammonia that Frodo is holding? #LOTRnerdalert

For a long time, it was thought that ammonia was the The One Toxin to Rule Them All when it came to causing encephalopathy in patients with hepatic disease. Ammonia is produced during the metabolism of nitrogen-containing compounds, often in the usual processes of gut flora, and then it is normally cleared from the bloodstream by the liver. So if the liver is not working properly or blood flow is bypassing the liver, the thought was that an excess of this ammonia (aka hyperammonemia) caused altered mentation.

So is ammonia really the source of all evil in hepatic encephalopathy (HE)?

Bit hard to say, tbh.

We do know that ammonia is neurotoxic in high levels, and people with cirrhosis do often have elevated blood levels of ammonia. But what about the plethora of medications they may be taking that perhaps aren’t getting fully cleared? What about that benzodiazepine? That narcotic pain med? Couldn’t a build up of those be just as detrimental to mentation?

Definitely. So ammonia may be part of the picture, but it certainly isn’t everything.

Which is why we don’t really check ammonia levels all that often anymore when trying to diagnose or monitor patients with HE. Even if they have an elevated ammonia level, is it just chronically elevated due to liver disease? And what level of ammonemia correlates with what level of toxicity? Or what level is nontoxic?

shrug

So, checking serial ammonia levels is no longer done because it’s just not a reliable clinical correlate for clear or unclear mentation.

So how is HE diagnosed if it’s not by a serum level?

First, patient history is important. Does the patient have a history of liver disease?

Second, clinical presentation. Of course, encephalopathy is a token hallmark (dur, it’s in the name). But there are LOTS of things that are on the encephalopathy differential - infection, stroke, etc. So what’s special about HE?

Patients with HE often present with asterixis, or “hand flapping”. When providers ask a patient with a history of liver disease to hold out their hands in front of them, their hands may flap. Kinda like a bird flapping its wings. This is a classic physical exam finding for HE, although it can be found in other diagnoses as well. If it’s bilateral though, it’s usually associated with a metabolic encephalopathy rather than electrolyte imbalances or other causes.

Once a diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy is suspected, it’s time to eliminate the toxins. As the pharmacist, one way to minimize toxins is to review patients’ medication lists to see if there are hepatically-cleared medications that may not be getting eliminated properly in the setting of cirrhosis. Are there suitable alternatives? Should the dose be decreased? How will you monitor for adverse effects or accumulation? #lessismore

Another way to eliminate the toxins and help the patient clear mentally is to…eliminate the toxins! That’s right, we try to physically remove the toxins using medications. It’s like pharmacologic dialysis.

The most commonly used medication for hepatic encephalopathy is lactulose. That’s right, a synthetic, non absorbed sugar. The same sugar compound that smells terrible (if you don’t like licorice) and is used for constipation. Often it’s that bright Kryptonite green color (shout out to my Smallville peeps) that must be horribly unappetizing.

How does a sugar eliminate toxins?

So greeeeeeen… (Image)

Catharsis. Let’s circle back to high school chemistry for a hot second. Ammonia is NH3, neutral and uncharged. Ammonium is NH4+, a positively charged molecule. Neutral particles cross membranes in the body much more easily than charged particles (charged particles often require special transporters). So ammonia that is produced by normal gut flora can be easily absorbed into the bloodstream and wreak havoc if it builds up. BUT, enter lactulose, which does 3 things to decrease ammonia:

It is a powerful osmotic laxative. All that particulate, non absorbed sugary goodness draws fluid into the GI tract, and WHOOSH. Bowel movement. So less ammonia is absorbed from the GI tract.

The laxative effect also changes the pH within the bowel, making it more acidic. This acidic environment promotes the conversion of ammonia to ammonium. As a charged particle, ammonium is less absorbed across the GI lumen wall. Sneaky trap for ammonium in the GI tract, right?

The acidic pH in the gut produced by lactulose also kills off some of that ammonia-producing bacteria. This leads to less ammonia, period.

Pretty cool mechanisms for a sugar, right?

Lactulose : ammonia :: the flood at Isengard : the orcs. Definite catharsis of some toxins.

In the inpatient world during an episode of acute HE, patients may have orders for lactulose as frequently as every 2 hours with the goal being to produce a certain number of bowel movements in a day (usually 3-4). If a patient is too altered to accept PO lactulose, it can be given as a rectal enema, although retention of the fluid in an altered patient can be problematic. But it is an option, at least.

And for the record, being lactose-intolerant does not mean that a patient has to avoid lactulose.

Once a patient is having the target number of BMs and their mentation begins to clear, the lactulose is titrated to a more reasonable outpatient maintenance dose and interval. Of course, these chronic outpatient prescriptions for lactulose may still be 15-30 mL 3-4 times per day. Add that to all the previously mentioned downsides (color, smell, taste), and you can see why readmissions for hepatic encephalopathy due to non adherence is not an uncommon occurrence.

We talk about cephalexin QID being hard to achieve for cellulitis… How many people do you think will take some weird looking and not-so-great tasting liquid that many times a day?

That brings us to other pharmacotherapies. Other options for the treatment and maintenance of HE include rifaximin and polyethylene glycol. Let’s start with the antibiotic.

Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is a non-absorbed rifamycin antibiotic that kills off ammonia-producing bacteria in the GI tract. Because it is not absorbed, there is less systemic collateral damage from an antimicrobial stewardship perspective, although patients can still experience other systemic effects like peripheral edema, dizziness, and nausea. As maintenance therapy, it’s a PO tablet dosed as 550mg twice daily (much easier than a liquid 3-4 times per day). Sounds pretty good, eh? Why isn’t it first line then?

Hey, must be the money!

It is PRICEY, and often patients are unable to afford this as a chronic medication. Send those test scripts and check the insurance formularies prior to hospital discharge!

Then that brings us to polyethylene glycol (more commonly known as Miralax). For some time, there’s been a question as to whether the ammonia to ammonium conversion by lactulose is a crucial mechanism for therapeutic activity - or whether the more important part of HE treatment is just to produce bowel movements and lots of them in order to clear out the ammonia. (If it’s just a matter of having bowel movements, we have LOTS of options for that!)

So can we protect patients from having to drink copious amounts of yellow/green lactulose and substitute clear, (theoretically) tasteless polyethylene glycol?

IDK. Unfortunately, despite several past studies on the subject, this 2019 Cochrane review wasn’t overly conclusive. There are some ongoing clinical trials in the works, so perhaps they’ll shed more light on this, but for now we’re kinda left with…maybe…

It should also be noted that even if we save the patients the taste and smell of lactulose by using this alternative, several of the polyethylene glycol treatment arms in the studies certainly didn’t reduce volume of treatment. Some patients were drinking Miralax to the tune of liters. So volume could still be a potential barrier to effective treatment.

In summary, hepatic encephalopathy is a relatively common complication of cirrhosis that can greatly impact a patient’s quality of life. Acute and maintenance treatment options include lactulose (the mainstay), rifaximin, and polyethylene glycol, although none of these makes it particularly easy for patients to remain adherent. As the pharmacist:

Review your patient’s medications to ensure they are appropriate (and appropriately dosed) for hepatic dysfunction

Try to eliminate unnecessary medications

Consider any medications that can lead to altered mentation independent of liver function, and

Monitor for bowel movements with the chosen therapy (-ies)… Remember, no BMs = no toxin elimination!

Cirrhosis Complication #4: Variceal Bleeding

For this next section, we have to bring back some of the pathophysiology from Part 1. Think back to how fibrosis and cirrhosis leads to increased pressures in the portal vasculature, aka portal hypertension. Due to these increased pressures, blood vessels can become enlarged. These high pressure, large blood vessels are known as varices, and they are estimated to be present in the esophageal and gastric areas of the GI tract in about 50% of patients with cirrhosis. Also, the more severe the cirrhosis, the higher the prevalence of varices.

(Image)

The problem with a varix (the singular form of varices) is that it can rupture. And when it does, the pressure that led to its formation also leads to one heck of a bleed. Often, patients with variceal bleeds present with acute onset of hematemesis (throwing up blood) and/or melena (blood in the stool). As one would guess, this is bad. Like high mortality rates bad - at least an estimated 20% at 6 weeks after the bleed.

So let’s talk about what we do when someone with a history of cirrhosis presents with these symptoms. And then let’s also talk about how maybe we can prevent it from happening again.

Acute Management of a Variceal Bleed

For an acute variceal bleed, resuscitate first! This means giving blood transfusions and pressure support as needed (although mean arterial pressure - or MAP - shouldn’t be pushed much higher than 65mmHg since that will just increase portal pressures and aggravate the resultant bleeding). As for targeted pharmacologic measures, there are 2 main arms of treatment:

(Weren’t expecting that for a GI bleed, were you?)

Antibiotics during a GI bleed seem a bit random, I know, but I promise this isn’t completely out of left field! Giving antibiotics to cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, whether or not they have ascites, lowers the risk of infection (which can be up to 40% without prophylaxis!), the risk of rebleeding, and the risk of death. All pretty darn compelling reasons to give antibiotics.

Similar to our discussion about SBP in Part 1, coverage of enteric Gram negative organisms is key, which is why ceftriaxone is the preferred first line agent at a dose of 1-2g IV q24h x 7 days. Fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, are reasonable alternatives if there are contraindications to ceftriaxone; however, note the increasing rates of resistance as well as #allbadthingsquinolone hitting the spotlight.

One important caveat about antibiotic prophylaxis in cirrhotic GI bleeds - we know that this is a crucial, beneficial strategy in advanced cirrhosis, but we’re still not 100% sure about its efficacy or utility in less severe cirrhotics.

Vasoactive agents

The purpose of these medications is to induce splanchnic vasoconstriction. If we can lessen the blood flow in the splanchnic vasculature, that decreases blood flow in the portal system and should help to decrease bleeding.

When considering options for this purpose, there are 3 that you’ll read about. Vasopressin, which is a systemically-acting vasoconstrictor with several important adverse effects, including the potential for decreased cardiac output. Terlipressin is a synthetic and more selective vasopressin analog that is only approved in Europe, although there are ongoing clinical trials in the United States (albeit for an alternative indication). And octreotide, which is a somatostatin analog and splanchnic vasoconstrictor.

Octreotide is the most widely used vasoactive option for variceal bleeding. For this indication, it is given as a 50mcg bolus followed by a continuous infusion of 50mcg/hour. (To be honest, I’ve been perusing liver information for years, and I have yet to run across a really clear explanation of how octreotide actually causes splanchnic vasoconstriction. Haven’t found it yet. TBD.)

It should be noted that even though variceal bleeding is considered a type of upper GI bleeding, we don’t use proton pump inhibitors as a treatment strategy for variceal bleeding. PPI therapy is thought to alter normal gut flora and potentially lead to overgrowth of bacteria given the less acidic environment. In a disease state that already lends itself to a lower immune system and possible bacterial translocation to places they’re not supposed to be, PPIs may not be the best idea in cirrhosis…

Now that doesn’t mean that a lot (read: most) of these cirrhotic, acutely bleeding patients don’t at least initially receive some PPI therapy! When a patient is in the ER vomiting bright red blood, it’s not like we can just look at them and say, mmm, definitely not an ulcer, skip the PPI. So until ulcer is ruled out, often patients will receive both a PPI and octreotide.

EVL of a varix (Image)

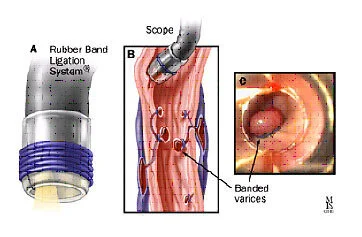

Now that our patient has been resuscitated and the acute bleed is stabilized, it’s time to figure out what the cause of the bleed is. This requires an EGD, or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (yes, it’s the best word for playing hangman ever). This is a procedure in which a scope is passed down the throat into the GI tract to try and visualize the source of the bleeding.

Once found, non-pharmacologic or endoscopic control of a bleeding varix can include sclerotherapy (injecting a substance to make the vessel collapse, which is no longer favored) and EVL, or endoscopic variceal ligation. EVL is otherwise known as “banding” or placing a rubber band around the bleeding vessel.

Secondary Prevention of Variceal Bleeding

Logically speaking, it would seem to make sense that if high pressure in the portal system is what leads to varices and their rupture, we just need to lower the pressure.

But remember how we treated the acute variceal bleed? By inducing splanchnic vasoconstriction as much as we can?

That’s reaaaally what we want to achieve in order to prevent future bleeding. And we do this with nonselective beta blockers.

This term “nonselective” is extremely misleading. What does nonselective mean? A mix of alpha and beta adrenergic antagonism? Or a mix of the beta adrenergic receptors?

Contrary to what I thought throughout approximately 99.95% of my time in pharmacy school, the nonselective beta blockers used for variceal bleeding prophylaxis DO NOT cause vasodilation and therefore lower pressures in the splanchnic system. Trust me when I say I know this is tempting to consider since some “nonselective” beta blockers are used for hypertension.

So let’s define nonselective in this context.

When I say nonselective beta blockers for the prevention of variceal bleeding, I’m referring to drugs that exhibit a mix of beta-1 and beta-2 antagonism. As in, they are not selective for beta-1 (e.g., metoprolol). They are also not active against a mix of alpha-1 and beta receptors (e.g., carvedilol, labetalol). In fact, in the case of cirrhosis, we may not want alpha-1 antagonism at all since this leads to more potent vasodilation. Alpha-1 antagonism is what makes carvedilol and labetalol so useful as antihypertensives…but it’s also what can induce more hypotension, thereby leading to hypoperfusion of end organs in a tenuous disease state like more advanced cirrhosis.

No bueno.

So for cirrhosis, we’re usually looking to nadolol and propranolol, which antagonize beta-1 and beta-2 receptors. To keep straight what effects these receptors have, remember this: you have 1 heart and 2 lungs.

A review of the effects of AGONISM of adrenergic receptors. Pro tip: learn one direction, either agonism or antagonism, and then just think of the opposite when needed. (Image)

In the heart, where most of the beta-1 receptors are located, beta-1 antagonism leads to decreased chronotropy, or lower heart rate. This can lead to reduced cardiac output.

In the lungs (and other periphery), beta-2 antagonism leads to smooth muscle contraction, which leads to vasoconstriction.

I know this is confusing!!! But remember albuterol is a beta-2 agonist that leads to smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs to alleviate bronchspasms. So now we’re talking the opposite with beta-2 antagonism.

So essentially, nadolol and propranolol can cause vasoconstriction and decreased cardiac output. Both of these effects would have the ultimate ending of less blood flow through the splanchnic system, thereby (hopefully) preventing future variceal formation and bleeds.

Voila. Phew!

Now that we have spent so much time talking mechanisms, I have news. We don’t actually use these nonselective beta blockers nearly as much as we used to. They aren’t really considered a universal truth anymore. We used to think, hey, you have varices and/or you’ve had a variceal bleed, pharmacologic therapy for you! With some additional studies, the more favored thought is that there’s only a “window” of the cirrhosis disease course when this is true.

Maybe Sauron wasn’t actually the reason for Frodo’s dizziness and fatigue here. Maybe Frodo started taking propranolol (for his anxiety about getting into Mordor).

For patients who have early cirrhosis and maybe only baby varices, beta blockers aren’t really all that great at preventing more or worsening varices. And like all drugs, they’re not without possible adverse effects (e.g., fatigue, edema, dizziness, impotence, masking hypoglycemia, exacerbation of bronchospastic disease). So benefit likely does NOT outweigh risk in these patients.

For those who have moderate to large varices, nonselective beta blockers may be used for both before and after a bleeding event. This means not only do we think about starting these as secondary prevention, but we may even consider starting these as primary prophylaxis in certain patients!

For patients who have more advanced cirrhosis, characterized by refractory ascites, hypotension, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or evidence of end organ hypoperfusion (hepatorenal syndrome), nonselective beta blockers seem to only make things worse. Remember the decrease in cardiac output mentioned earlier? Not super helpful when perfusion of organs is already an issue. And decreases in MAP too? Yeahhh, not so great.

Summary of Cirrhosis Part 2

Alright, so if you can gather your brain from all that chat about adrenergic receptors, it’s time to summarize:

Hepatic encephalopathy is altered mentation due to build up of toxins, including ammonia (although perhaps it is not the One Toxin to Rule Them All).

Do not check serial ammonia levels or try to correlate ammonia levels with mentation. It’s like trying to associate oranges and zebras.

Lactulose is the go-to option for hepatic encephalopathy, although perhaps polyethylene glycol has a role as well. Try rifaximin if it’s affordable. Ultimately, produce bowel movements!

Variceal bleeding results when elevated portal pressures lead to the bulging and rupture of blood vessels, usually in the esophagus and/or stomach.

Acute management of the variceal bleed is 2 pronged: octreotide for splanchnic vasoconstriction and ceftriaxone (or alternative) for Gram negative infection prophylaxis. Use discretion when considering PPIs.

Prevention of variceal bleeding may incorporate the nonselective beta blockers nadolol and propranolol, but not everyone with cirrhosis and a bleed is a candidate due to their induction of hemodynamic changes.

Stay tuned for hepatorenal syndrome, which will be Part 3 of this liver-loving series!

We combined ALL of the posts in this Liver series AND our Kidney series into a single PDF. If you’d like a downloadable (and printer-friendly) version of this article, you can get one here