Clinical Trials That May Change What You Were Taught in Pharmacy School: Part 1

Steph’s Note: Today we get to introduce a new author to the blog, Christian González-Hernández. He is a 4th-year student at Nova Southeastern University, Puerto Rico campus, who is currently in the residency interviewing process. Per his own words, he’s “someone who basically reads clinical trials for fun, it’s like gossip in the pharmacy world .😈 And it’s actually a great way to have a greater arsenal in your intervention repertoire.”

Essentially, he was born for tl;dr!

In the future, he would like to obtain a BCPS and BCIDP or BCCCP and work as a clinical pharmacy specialist. He might even split that time with some teaching in a college of pharmacy. He likes reading and learning about many disease states, and his areas of interest are those where you get to see many organ systems and comorbidities overlap - especially internal medicine, critical care, and infectious diseases.

Let’s paint a picture.

That moment when you’re asked a question on rounds that you USED to know the answer to…and you feel like you’re losing your edge.

You’re in pharmacy school, trying to keep your head above water as information is thrown at you like a dartboard. Then you bust your butt on rotations and studying for the NAPLEX, and phew! You land The Job. You can breathe for a moment. But then, guess what… Routine strikes, you feel you’re not quite as sharp when asked questions, and that hunger to learn more settles in.

Or maybe it’s not self-driven - but rather you get that question during rounds that sends you back to the PubMed trenches.

After school, life unfortunately doesn’t really get less stressful. Often, it’s even BUSIER. So, in order to maintain some semblance of work-life balance, it’s easy to grow accustomed to keeping our minds off pharmacy once we get home from work. But little by little, new clinical trials are released. Maybe you have your news feed set up so you see these in your inbox, but do you give them more than a quick glance?

Some publications perhaps just reinforce what we were taught during pharmacy school, but others take the pharmacy world by storm and throw away what we were taught in school. Isn’t it amazing?!

I’m still a student, currently doing APPEs. It’s only been 7 months since the last time I had a formal test (and trust me, I am so glad I have not seen a damn green screen in that time), but the number of clinical trials that have been published in so little time is amazing. How many new FDA approvals have been announced. How many clinical practice guidelines have been updated.

And it finally struck me.

If you do not keep yourself updated, you will lose your edge. You won’t be practicing evidence-based medicine for the good of your patients! So perhaps those emails deserve more than a quick glance at the headline.

Medical sciences are like anime. But not like the new ones that have a year recess between seasons. But rather like the old ones that kept releasing new episodes weekly uninterrupted for years, and if you disconnected for even a hot second, you were lost in the story.

But worry not! As always, we at tl;dr pharmacy have your back and will guide you through four recently published clinical trials that may have an impact on future clinical practice. Let’s talk the latest in cardiology.

Updates in Heart Failure Literature

(FYI, we’re gonna do a brief spotlight on heart failure in this post. But if you need a full review of heart failure, check out Heart Failure: Parts 1, 2, and 3 here on tl;dr. We also have a handy review of left ventricular assist devices if you want to go for the full range of therapies.)

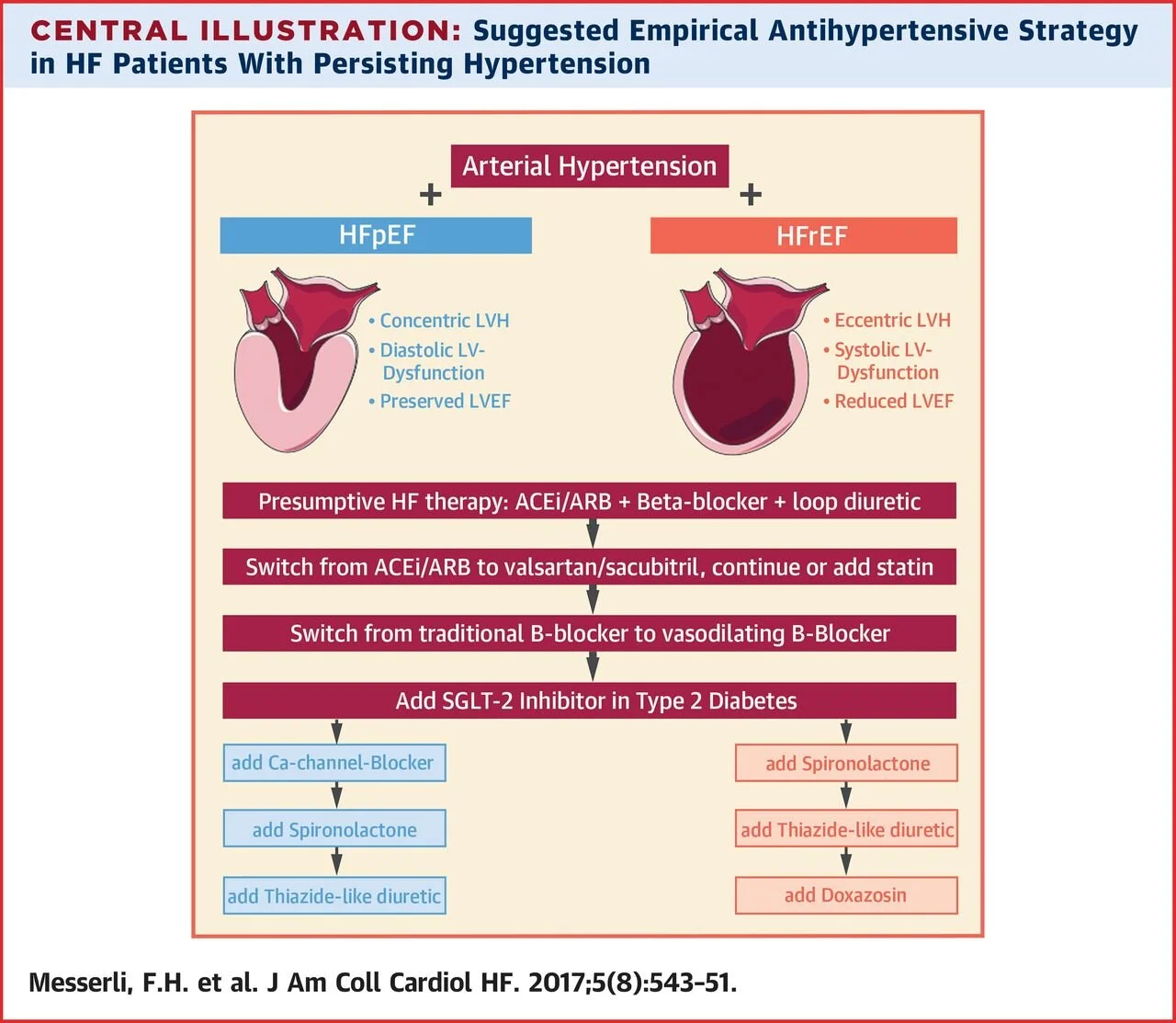

(Image)

Heart failure is a common cause of hospitalizations in Medicare recipients with extremely high readmission rates and costs to the overall US healthcare system. Essentially there two types of heart failure. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). HFrEF is basically the inability of the heart to effectively pump blood out of the heart when contracting. Pharmacotherapy for HFrEF has been extensively studied, and most of the treatments you have learned about are geared towards this type of heart failure.

To be diagnosed with HFrEF, the ejection fraction (EF) should be less than 40%. Some causes of this type of heart failure include:

Coronary artery disease

High blood pressure

Aortic stenosis

Arrhythmias

Cardiomyopathy

Essentially, anything that weakens the cardiac muscles can cause this. For this type of HF, the overall backbones of therapy are an ACE-inhibitor or ARB + Beta-Blocker (data favors carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol) + a loop diuretic for symptom relief.

In recent years, the addition of sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) has been common because it proved to be superior to ACE inhibitor therapy in the 2014 PARADIGM trial. This study compared sacubitril-valsartan to enalapril in HFrEF, and sacubitril-valsartan led to a 20% reduction in hospitalizations or death. BAM. FDA approval for HFrEF. Fast forward, Entresto (or “Ernesto” as I used to call it in my first year of pharmacy school) has been established as one of the power horses in the treatment for HFrEF.

Another common drug added to the backbone regimen is spironolactone, especially in patients with a severely reduced EF less than 35%. With the exception of loop diuretics, all drugs have demonstrated reductions in mortality and hospitalizations.

On the other hand, HFpEF (EF >50%) is when the ventricles contract normally, but the heart does not relax effectively. This makes it so that the heart does not fill properly. This type of heart failure is common in elderly patients and, for some reason, women. So far, no drug has been demonstrated to significantly reduce mortality and hospitalizations in this population.

This brings us to our first trial of the post.

The 2019 PARAGON-HF Trial

This trial was one of the most awaited studies of the last year. If a study ever needed a drum roll, it’s this one.

As we noted above, most evidence for heart failure treatment lies with HFrEF. So any time a drug is studied for HFpEF, you better believe that study is going to be hawked by the medical community.

In most heart failure studies, there are two big endpoints used to measure the efficacy of a drug:

Reduction in the number of hospitalizations AND

Reduction in mortality

In the PARAGON-HF trial, Entresto (target dose 97 mg sacubitril/107 mg of valsartan) twice daily was compared to valsartan (target dose 160 mg) twice daily. The trial included patients who were 50 years of age or older with symptoms of heart failure, an EF of at least 45%, and elevated natriuretic peptide levels. The primary outcome was a composite of total hospitalizations for heart failure and death from cardiovascular causes. After 35 long months, the results were in.

(Image)

And the results were more controversial than talking about politics in an election year. There were 894 primary events in 546 patients in the Entresto group, and in the valsartan group, there were 1009 events in 557 patients. At first sight, numerically, it looks like there is a difference. But the seagull over here will tell the rest of the story.

The incidence of death from cardiovascular causes was 8.5% in the Entresto group and 8.9% in the valsartan group (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.16). There were 690 hospitalizations for heart failure in the Entresto group and 797 in the valsartan group (rate ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.00). Neither was statistically significant. Boo.

Quality of life and New York Heart Association functional class were improved in the sacubitril–valsartan group. But before we move on to what implications this may have, if any, on actual practice, there are other things that need to be looked at. In most trials, subgroup analyses or secondary outcomes may provide us with more information than you may think.

Once we look at the subgroup analyses, we can see that Entresto seemed to have a greater benefit in female patients and patients with an EF of less or equal to 57%. These might be interesting findings and perhaps they may help you to determine which patients you might consider this therapy for, but it’s hard to draw any hard and fast conclusions from these secondary analyses.

Now comes the nitty-gritty. Would I recommend Entresto on a patient with HFpEF?

My answer would be...YES. Mainly because there’s really nothing else that has resulted in a significant difference in the HFpEF population. (One of the last highly-anticipated HFpEF studies was the 2014 TOPCAT trial, in which spironolactone fell short versus placebo in decreasing cardiovascular death - although there was some interest in the secondary hospitalization reduction outcome…).

Another piece to consider is that the comparator drug may have had an effect in terms of reducing death or hospitalizations. In the 2003 CHARM-PRESERVED trial, candesartan was compared to placebo in patients with HFpEF. Candesartan didn’t show any mortality benefit, but it did have a statistically significant reduction in hospitalizations. So perhaps the impact of the valsartan alone in HFpEF made it more difficult for Entresto to show a statistical benefit in the PARAGON-HF trial.

Lastly, would a larger sample size have been able to detect a difference in terms of the primary outcome? Who knows, but that is a question many are asking.

As of now, there are several studies that are recruiting or are active in the topic of HFpEF. Some of the drugs being studied in this patient population include carvedilol SR and dapagliflozin. Oh, and speaking of dapagliflozin…

The DAPA-HF Trial

So we’re still talking within the realm of heart failure, but we’re switching gears to the DAPA-HF study. This study assessed the efficacy of dapagliflozin (Farxiga; yes, the same SGLT-2 inhibitor that is used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus) in patients with HFrEF.

FYI, if you need a quick review of oral anti-diabetic agents, check out here and here and then come back for this heart failure discussion!

DAPA-HF was a phase 3, placebo-controlled trial of 4744 patients with New York Heart Association Class II, III, or IV heart failure and an EF of 40% or less when randomized. Patients were given either dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily or placebo. The primary outcome was a composite of worsening of heart failure (aka hospitalization or urgent care visit that resulted in IV drug administration or cardiovascular death).

(Image)

After 18 months, the primary outcome occurred in 386 of 2373 patients in the dapagliflozin group and 502 or 2371 placebo patients. This was a significant difference in reducing the worsening of heart failure! Which is quite an accomplishment. But before going full Oprah mode giving dapagliflozin to all of your patients, there are a few things that should be considered.

First, patients were allowed to take other heart failure medications, which is not a bad thing… But the authors didn’t report how many background HF medications patients were taking, and we do not know if they were optimized in terms of dosing.

Therefore, we do not know for certain the impact those other medications could’ve had on the overall primary endpoint. Another way of looking at it is this - if patients were fully optimized on their baseline HF therapies, how much more would dapagliflozin add?

We don’t know based on this study.

Second, remember when I said that you can also get valuable information from subgroup analyses? The same principle applies here when we look at the subgroup analysis in terms of heart failure severity. Most patients in the study were classified as NYHA II, meaning we are not talking about severe heart failure. In the subgroup analysis, there was a significant difference in the primary outcome in patients with NYHA class II who were taking dapagliflozin, but patients with NYHA III-IV did not have the same significant reduction that was seen in patients with NYHA class II.

So how do we put DAPA-HF in context with previous studies?

Back in 2015, the EMPA-REG trial showed that a cousin SGLT-2 inhibitor, empagliflozin (Jardiance), reduced the risk of developing cardiovascular outcomes and death. Shortly afterwards, these findings were replicated with canagliflozin (Invokana) in the 2017 CANVAS studies. Of course, CANVAS is also what unveiled that pesky risk of amputations with canagliflozin…so it’s not a total knight in shining armor.

But basically, SGLT2- inhibitors reduce negative cardiovascular outcomes by reducing hospitalizations and death related to heart failure (although as the 2019 DECLARE-TIMI 58 study demonstrated, this benefit didn’t necessarily extend to risk of stroke or MI like some other anti-glycemic medications).

All of this being said, in the summer of 2019, the FDA granted fast track designation and subsequent approval for dapagliflozin given its reduction in risk for heart failure hospitalization among adults with type 2 diabetes who also have cardiovascular disease or multiple CV risk factors based on the findings of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial.

A few weeks later, the FDA granted fast track designation once again to dapagliflozin for reducing the risk for cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure among adults with heart failure with a reduced or preserved ejection fraction. This second designation was based on the findings of the DAPA-HF trial. Most importantly, that designation has two extremely important details:

There is NO mention of the words: glucose, Type, 2, Diabetes, Mellitus, sugar, endocrine

There IS mention of the words: preserved ejection fraction.

If the PARAGON-HF trial was the disappointment of the 2019 European Cardiology Congress, the DAPA-HF trial was the MVP!

But before we get all crazy, remember that the DAPA-HF trial did not report numbers of patients with HFpEF!! And yet, there it is in the FDA indication…

The fast track designation is based on two upcoming studies that are expected to be completed in the next year. The DELIVER and DETERMINE studies are evaluating the effects of dapagliflozin specifically in patients with HFpEF. The DAPA-HF trial basically confirmed previous studies’ assessments of beneficial cardiovascular outcomes with SGLT-2 inhibitors, regardless of glucose-lowering effects or type 2 diabetes status.

In any instance, it will be fun looking forward to the impact this trial may have on current practice and future guidelines. As a matter of fact, the 2020 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes recommend the addition of a SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), high risk of ASCVD, or HF regardless of A1C levels, which basically adds another layer when considering additional pharmacological agents in patients with type 2 diabetes.

So, as everything stands now, the addition of a SGLT2 inhibitor seems like a very reasonable choice in patients with concomitant diabetes and heart failure. In patients with heart failure, without diabetes, it does not look like a clear-cut decision, but it IS an interesting possibility to keep an eye on with the pending DETERMINE and DELIVER studies.

UPDATES IN SECONDARY STROKE PREVENTION LITERATURE

Moving on from heart failure, we’re now going to chat stroke prevention. Specifically, secondary prevention, aka how do we stop this bad thing from happening AGAIN after a first event.

The POINT Trial

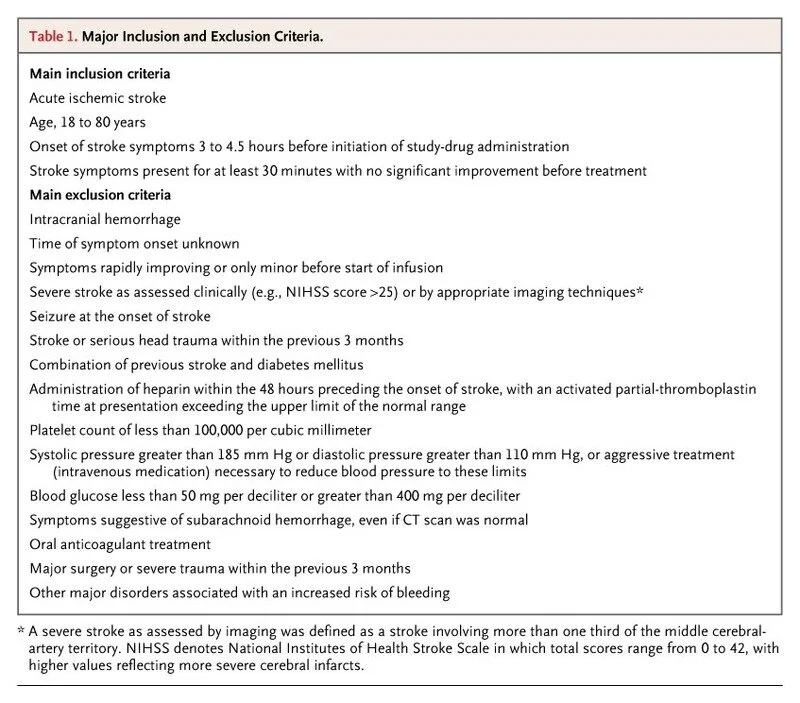

Sorry, explaining the full exclusion and inclusion criteria for IV alteplase is a story for another day. But here’s the original 2008 ECASS trial inclusion/exclusion criteria to get you started. (Image)

After the update to the stroke guidelines in late 2019, the POINT trial pretty much immediately gained the status of landmark trial. In many cases of acute ischemic stroke, patients with moderate-severe symptoms are given IV alteplase.

Before the 2013 CHANCE trial, patients with mild symptoms (aka a Transient Ischemic Stroke (TIA)) had no real treatment. The CHANCE trial compared placebo plus aspirin versus clopidrogel 300 mg once followed by 75 mg for up to 90 days PLUS aspirin 81 mg for 21 days. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) for 21 days followed by clopidrogel monotherapy for 90 days resulted in a reduction in stroke during the follow-up period.

Great, right? Why haven’t we been doing DAPT after stroke since 2013 instead of waiting until 2019??

Well, CHANCE was only conducted in China, raising some issues about applicability to other populations. Previous stroke guidelines suggested the DAPT regimen used in CHANCE was an option for patients after a TIA who did not receive IV alteplase - but it was not a strong recommendation.

Fast forward to 2018, when the results of the POINT trial were published. 4881 patients were randomized in 269 centers to receive either clopidogrel at a loading dose of 600 mg on day 1, followed by 75 mg per day, plus aspirin (at a dose of 50 to 325 mg per day) for 90 days or the same range of doses of aspirin alone. Aspirin dose was selected by the site investigator at each site. The primary outcome was a composite of major ischemic events, which was defined as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from an ischemic vascular event, at 90 days.

The trial was stopped early, mainly because there was a clear tendency towards reduced primary outcome events in the DAPT group (albeit along with an increase in bleeding events in the same group). Major ischemic events occurred in 121 of 2432 patients (5%) receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin and in 160 of 2449 patients (6.5%) receiving aspirin alone (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.59-0.95, p=0.02). Twenty-three bleeding events occurred in the DAPT group versus 4 in the aspirin alone group. This came as a surprise since there was no difference in bleeding between groups in the CHANCE trial. So, we need to assess what was done differently between both trials:

CHANCE trial used a lower clopidogrel loading dose than the POINT trial

That being said, most bleeding occurred later in the POINT trial and not in the first few days

Aspirin dose was chosen by investigators. In the POINT trial:

3012 patients were on doses up to 81 mg daily

1131 had doses >100 mg

The difference in duration of DAPT

DAPT lasted 21 days in CHANCE trial, while it lasted the full 90 days in the POINT trial

Trial population

Clopidogrel is a prodrug, therefore a difference in metabolism could be possible between the included Asian population and the USA population

Most likely the difference in outcomes between CHANCE and POINT was caused by some combination of these 4 hypotheses. Regardless, given the risk of developing a full stroke after TIA is higher in the early days after the initial event but also that the full 90 days of DAPT seemed to lead to more bleeding, the 2019 consensus guidelines recommend to continue DAPT for 21 days after a TIA incident. The detailed text explaining the recommendation mentions that continuing DAPT more than 30 days after a TIA will likely lead to no added benefit.

Using the information provided by both trials, it would probably be wise to limit DAPT to 21-30 days after a TIA to limit the CHANCE (wink, wink) of bleeding.

The MAGELLAN Trial

Ok, so this one’s not actually a new trial. But it IS one that has recently had a new impact.

One state’s experience with life after DOACs. (Image)

The MAGELLAN trial was published in 2013, and in combination with the 2018 MARINER trial, the FDA decided to approve rivaroxaban for VTE prophylaxis in at-risk acutely ill medical patients not at high risk of bleeding in October 2019. Even though rivaroxaban is not the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) with an indication for VTE prophylaxis (betrixaban got the indication in 2017), it is one of the most widely used DOACs.

In the MAGELLAN trial, 8101 patients were randomized to receive either subcutaneous enoxaparin 40 mg once daily for 10±4 days or rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily for 35±4 days. Patients were at least 40 years old and hospitalized. The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of asymptomatic proximal or symptomatic venous thromboembolism by day 10 for noninferiority and by day 35 for superiority.

By day 10, the primary endpoint had occurred in 78 patients in the rivaroxaban group (2.7%) and in 82 patients in the enoxaparin group (also 2.7%), meeting noninferiority criteria. At day 35, the primary endpoint occurred in 131 patients in the rivaroxaban group (4.4%) and in 175 patients in the enoxaparin group (5.7%), meaning rivaroxaban also met superiority criteria. Of course, rivaroxaban was accompanied by an increased risk of bleeding at both day 10 (2.8% vs. 1.2%, P=<0.001) and 35 (4.1% vs. 1.7%, P<0.001).

Let’s think for a sec here now. Results for VTE incidence were only reported up until day 35; therefore, it’s possible that the incidence of rebound or late thrombosis was not equitably assessed. (That being said, this isn’t really something that is routinely measured or reported in other trials… But let’s just play like we wanted to try to compare the 2 meds for this purpose.) Active enoxaparin was only given for 10 days whereas rivaroxaban was given for 35. So while there may have been at least some time to assess for rebound/late events post enoxaparin, there was definitely no way to check this for rivaroxaban.

Also, is it really a test of drug vs drug if they’re not given for the same duration? Can we fairly compare enoxaparin to rivaroxaban if the former was given for only 10 days while the latter was administered for 35?

On that note, were we testing a hypothesis about duration of VTE prophylaxis rather than preferred agent in MAGELLAN?

Hmm. Interesting trial design, right?

As things stand today, the fact that there is not one, but TWO oral options for VTE prophylaxis is something amazing. But should we use these routinely in standard practice?

Probably not as a blanket rule. First, $$$. Second, there was an increased risk of bleeding with rivaroxaban in MAGELLAN. Third, efficacy results from MARINER leave us still wondering whether the cost is worth the benefit (i.e., no significant difference was seen in the primary outcome of symptomatic VTE or VTE-related death, although rivaroxaban did reduce symptomatic VTE compared to placebo). Is that enough to jump on the rivaroxaban train?

That being said, nothing in medicine is EVER a blanket rule. So perhaps the pockets where rivaroxaban may be an option for VTE prophylaxis could include…

Hospitalized patients who are reluctant or refuse to receive injections

Patients with a history of HIT who don’t want injections but warrant DVT prophylaxis

Perhaps morbidly obese patients (>120 kg or BMI >40) given reduced enoxaparin absorption in this population. But this thought is reeeeally quite tenuous since we don’t have a great repository of data for DOACs in obesity just yet. And at least we can monitor enoxaparin with anti-Xa levels when needed. (Tip: check out this tl;dr post on DOAC use in special populations for more dos and don’ts with DOACs.)

Final Thoughts

I really hope that this article reaches many people and benefits many more. Clinical trials are what keep our field (and the medical sciences overall) improving each and every year. If you’re feeling like you’re on shaky ground with your journal clubbing skills, head over to tl;dr’s Biostats post series. Or learn what that p-value really means.

Every little bit of knowledge helps, and know that you’re not alone if you feel hesitant about reading studies. That’s why we journal club as a profession! We learn from each other.

I would like to encourage everyone to at least subscribe to a weekly newsletter in any of your areas of interest from any of the scientific journals. You don’t even need to read every clinical trial there is available but only those that interest you and think may impact your practice. This will benefit your practice and improve patient care!

Hopefully, this will not be the last time you guys hear from me nerding about clinical trials. Be back with another segment in the future!