Chemo-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV) in a Nutshell

Editor’s Note: Please join me in welcoming Savannah Mageau, PharmD to the tl;dr family! Although her graduation was postponed, Savannah Mageau completed her training at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and is still getting used to the whole notion of “Savannah Mageau, PharmD.” She is excited to be joining the Clinical Research and Pharmacovigilance team at Merck, where she will be developing clinical regulatory writing portfolios for pipeline products. Her primary therapeutic area of interest is hematology/oncology, which, as you may have guessed, is the star of the show here. Now that she has passed her boards, she spends her down time practicing yoga and doing other socially-distant activities.

BTW - We compiled ALL of our Oncology Supportive Care posts into one handy, downloadable (and printer-friendly) PDF. You can get your copy of it here.

When most people think of cancer treatment, hair loss and nausea commonly are top of mind. And to be fair, both are significant concerns for patients with cancer.

Of course, those are far from the only concerns in oncology. There’s the affect on family, treatment logistics, cost, changes in taste, fatigue, and even survivorship.

We won’t be talking about yoga today, but there’s some interesting data suggesting its potential benefit in breast cancer patients!

Looking at the list of patient concerns over time, you can actually see how far we’ve come with treatment.

In 1983, the top treatment-related concern for cancer patients was emesis.

By 2017, that concern shifted to how much treatment will affect the patient’s family or partner.

Still, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is a critical area for pharmacist intervention.

Simply put, the better we can manage CINV, the bigger impact we can have on the patient’s quality of life (and, of course, adherence to treatment).

Chemo-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV) Pathophysiology

Before we jump in, you might be wondering why some patients seem to have such a rough time with nausea compared to others. We’ll get to that in a bit, but first, let’s discuss the pathophysiology of CINV.

Nausea and vomiting (N/V) can result from both central and peripheral pathways:

Central pathways - The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) (yes, that’s actually a “thing” in your brain, and that IS it’s real name) comes into contact with toxins (chemotherapy). It responds by releasing neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, and substance P) which may trigger vomiting

Peripheral pathways - N/V can occur when serotonin receptors (oh, hello again) in the GI tract are stimulated due to mechanical stress and direct mucosal injury

Your GI tract after chemotherapy starts.

There are also some patients who experience potentiated nausea with vertigo (thanks vestibular system), and a few more that might feel nausea as a complication from neuropathy that slows down their GI tract.

But the above pathways are responsible for most cases of CINV.

OK, so we know what causes CINV, now we need to understand the definitions of CINV.

Why?

Because we use different drugs (in different combinations) to treat different types of CINV!

There are five flavors (cringe) of CINV: acute, delayed, anticipatory, breakthrough, and refractory.

BTW, these terms are important when reading clinical trials on this topic...or if you’re taking the NAPLEX.

Acute - N/V occurring within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy

Delayed - N/V occurring 24 hours to several days (2-5) after chemotherapy

Anticipatory - N/V occurring before treatment as a conditioned response

Breakthrough - N/V occurring despite appropriate prophylactic treatment

Refractory - N/V occurring during subsequent cycles when prior prophylaxis or rescue failed

Chemo-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Risk Factors

So who is the prototypical patient that’s most likely to have CINV?

For starters, you have to look at the emetogenicity of the chemo regimen that the patient is receiving. I’ll cover this in more detail later (I have much to say!), but for now, here’s the breakdown:

High emetogenic risk (≥90% frequency of emesis)

Moderate emetogenic risk (30-90% frequency of emesis)

Low emetogenic risk (10-30% frequency of emesis)

Minimal emetogenic risk (≤10% frequency of emesis)

In addition to the emetogenic risk of the chemotherapy agent, how the agent is administered can also increase the risk of CINV. Specifically, bolus dosing carries a higher risk than slower infusions. This is because the CTZ is exposed to higher levels of drug with bolus dosing (that whole AUC and Cmax thing).

Ignoring the inherent risk of the chemotherapy itself, are there any patient-specific risk factors that make CINV more likely? Absolutely.

Women, especially young women (less than 40 years old) are at a higher risk for CINV than other patients. Especially if they have a history of motion sickness or if they suffered from morning sickness during pregnancy.

Also be careful in patients with a history of anxiety as that increases the risk of CINV.

On top of that, having prior chemotherapy treatment experience increases the likelihood of CINV. So, all things being equal, a patient on their third line of chemotherapy is at a higher risk than someone on their first line.

Additionally, has the patient experienced nausea with a particular regimen in the past? If they experienced nausea on Cycle 1, there’s a good chance they’re going to experience it again on Cycle 2.

Surprisingly, alcohol consumption is actually associated with LESS nausea. This is especially true for episodic, binge drinkers (>4 drinks per episode). You may want to avoid telling your patients that though.

Chemo-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Prevention and Treatment

So how do we treat CINV? I’m glad you asked! This is where things get fun. Let’s talk antiemetics.

But first, let’s set up 2 important rules that govern our approach to CINV.

It is much easier to prevent CINV than it is to treat it

We combine antiemetics in a step-wise fashion (not that different from asthma step therapy) to achieve maximum effect

We’ll dive deeper into the “forest” view of CINV soon, but first let’s talk about each individual class of antiemetic drugs.

Serotonin (5-HT3) Receptor Antagonists

5HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3 RAs for short) block serotonin (both centrally and peripherally) and they are one of our “go-to” drugs for the prevention of CINV. They are usually given 30 minutes before chemotherapy.

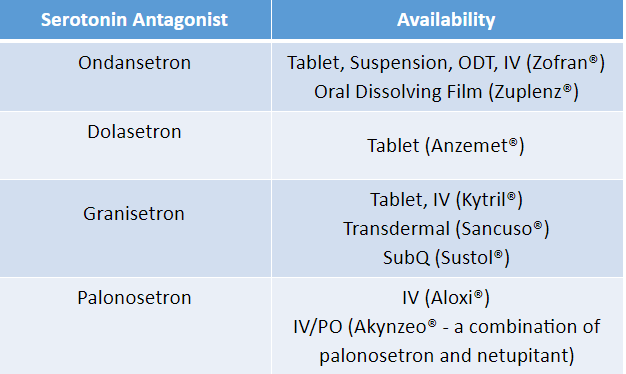

Our friends ondansetron, granisetron, and dolasetron make up the first generation of the 5-HT3 RA class. Each is available IV and PO, with the exception of dolasetron, which should only be given orally for safety reasons.

There are a few notable formulations available with 5-HT3 RAs. Ondansetron is available as an Oral Disintegrating Tablet (ODT), which is pretty handy. Sublingual absorption (you technically place it on TOP of the tongue) means it gets into the bloodstream faster than normal PO administration. Also, you know what people who are nauseous don’t want to do? Grab a glass of water and swallow a pill. Ondansetron ODT helps get around that. There is also an ondansetron oral dissolving film (Zuplenz).

Addtionally, granisetron is available in both a transdermal patch (Sancuso) and an extended release subcutaneous injection (Sustol). These formulations are potentially useful for delayed nausea and vomiting (Note: the IV and PO formulations of granisetron is NOT a good choice for delayed n/v).

For all first generation 5-HT3 RAs, be on the look out for constipation, headache, and QTc prolongation. These are all generally dose-related, but can be synergistic with other drugs.

Palonosetron is our (one and only) fancy second generation 5-HT3 RA. With a half-life that is roughly 5x longer than the first generation 5-HT3 RAs, it covers both the acute and the delayed phase of CINV with a single dose.

Palonosetron is available IV as a single agent (Aloxi). It’s also available in combination with another antiemetic, netupitant, under the brand Akynzeo. Akynzeo is available both IV and PO (don’t worry, we’ll talk more about netupitant in a bit).

Besides a longer half-life, palonosetron has another potential advantage...

Though the risk of QTc prolongation cannot be completely ruled out, a study in 2016 demonstrated the magnitude of effect is less than the threshold for regulatory concern. Said another way, we’re less worried about QTc with palonosetron than we are with all 1st generation 5-HT3 RAs.

All that said, the risk of headache and constipation is still very present. And while those sound like such “benign” side effects, you really don’t want to ignore them. Anecdotally, headaches seem to be more likely in patients that suffer from migraines (which makes sense since we use 5-HT3 AGONISTS to treat migraines).

And regarding constipation, a bowel regimen can be necessary, especially when opioids are in the picture.

Alright, so in summary…here’s where we’re at with our 5-HT3 RAs:

Dexamethasone

Wait, what? Are you sure we aren’t in the rheumatoid arthritis section? Are we talking about the RECOVERY Trial for COVID?

Nope, we’re in the right place. The exact mechanism of dexamethasone in CINV is unknown, but here are some hypotheses if you’re interested. What IS clear, however, is that dex works for low levels of nausea. And, given as a premed, it has the added benefit of helping to reduce the likelihood of an infusion reaction to drugs like paclitaxel.

Why dexamethasone and not any other corticosteroid, you ask? Dex is preferred for a few reasons. It’s long acting, it’s got fantastic penetration of the blood brain barrier, and it has ZERO mineralocorticoid activity. That means you won’t have any issues with sodium and water retention.

Check out this chart for a quick refresher on our common steroids.

Dexamethasone can be used as monotherapy for low-emetogenic potential treatments, or in combination with serotonin antagonists (see the 5-HT3 RA sectoin above) for low or moderate emetogenic potential. With a dose 30 minutes before chemo, and repeated dosing for a few days after, you can get benefits in both acute and delayed CINV.

Since this is typically a short course, dexamethasone is pretty well tolerated, but be on the lookout for transient elevations in blood sugar, blood pressure, leukocytes…and increased energy and alertness. Look no further if you’re wondering why your patient can’t sleep.

In general, I recommend taking dex as early in the day as possible to minimize the effects on sleep. And ALWAYS take dex (or any steroid) with food to lower the risk of peptic ulcers.

There are certain lymphoma regimens that use prednisone as part of the treatment regimen (e.g., CHOP, where P is for prednisone). Prednisone is given at high doses (100 mg per day) for 5 days because it has lymphoma-fighting properties. It is not necessary (or appropriate) to use dexamethasone as an antiemetic for these patients, since they’re already getting so much steroid.

And speaking of using steroids as part of the treatment regimen, dexamethasone is given in high doses as part of many multiple myeloma regimens because of its anti-tumor effects. In this setting, it’s typically dosed as 40 mg given once weekly. That is a hell of a lot of steroid, though, so you may see some practices split this as 20 mg given over 2 days every week.

And one last dexamethasone clinical pearl - it has excellent oral bioavailability, so the IV/PO conversion is 1:1.

NK1 Receptor Antagonists

Here’s a nice image to tie it all together with the NK1 inhibitors (Image)

Remember substance P?

It’s a neurohormone (responsible for pain and inflammation) that binds to neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors.

Cool.

What does THAT have to do with CINV?

Enter the NK1 receptor antagonists (aka NK1 RAs or NK1 inhibitors).

NK1 inhibitors work primarily in the brain stem and are most beneficial for preventing delayed CINV.

For that reason they are only given in combination with a 5-HT3 RA and dex.

That’s worth repeating, so let’s reemphasize it.

If you come across a clinical scenario (or a test question) where you are giving an NK1 antagonist as monotherapy (or for anything other than CINV), that’s a huge red flag.

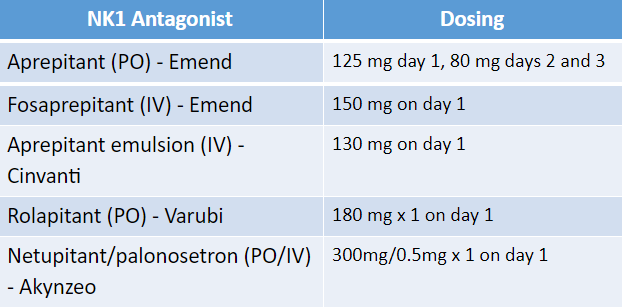

Here’s a rundown of our current NK1 inhibitors:

CINVanti….get it?!? I see what you did there…

From an efficacy standpoint, all NK1 inhibitors are considered equal. So why should you choose one over the other? Let’s discuss.

First, there’s the obvious PO vs IV consideration. From a patient compliance standpoint, if you were choosing the PO route, it would make sense to use Varubi or Akynzeo. Not that I’m trying to throw shade on PO Emend, but why wouldn’t you go with a single dose instead of daily x 3?

The next consideration is drug interactions. These guys, except rolapitant, are all moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors. Since NK1 RAs are pretty much always coadministered with dexamethasone (a substrate of CYP3A4), that can pose a problem. Historically, we’d get around this by preemptively reducing the dex dose from 20 mg to 12 mg, or from 12 mg to 8 mg.

Luckily, in the past couple of years, the NCCN Guidelines on Antiemesis have made this easier for us by just recommending 12 mg and 8 mg of dex up front. It’s no longer standard practice to give 20 mg of dex for nausea…and we no longer have to worry about dose reductions.

Still, we need to be mindful of other CYP3A4 interactions with aprepitant, fosaprepitant, and netupitant.

Back to rolapitant. It gets a pass from 3A4 interactions, but it makes up for it by having some CYP2C9 inhibition (watch out, warfarin). There used to be an IV formulation of Varubi, but it’s no longer in production due to a pretty high incidence of infusion-related reactions.

Rolapitant has the longest half-life of the NK1 inhibitors (up to 7 days), which makes it a great choice for delayed N/V.

One thing to highlight is that NK1 inhibitors are, for the most part, only administered once per cycle. The PO version of Emend is an exception, because its half-life necessitates 3 daily doses.

That said, (although you won’t find this in the NCCN Guidelines or on the package insert) you may see some practitioners give a repeat dose on Day 5 for a select few regimens. Usually this is for multi-day regimens that can cause delayed nausea and are highly emetogenic, such as BEP (used for testicular cancer). Another alternative is to use Varubi with its fantastically long half-life.

With the exception of drug interactions and infusion reactions (there are plenty of infusion reactions to Emend and Cinvanti too), NK1 inhibitors are well tolerated. Just make sure you’re only using them for CINV (and not as monotherapy), and you’re in the clear.

Dopamine Antagonists

Since dopamine (D2) is one of the neurotransmitters involved in the pathogenesis of CINV, blocking the receptor makes sense right?

The story begins with metoclopramide. Until the 1990s (when Zofran was approved), high dose metoclopramide was basically all we had for CINV. Metoclopramide is an interesting character in that at low doses it’s pretty much a straight D2 antagonist, but at high doses it starts to block 5-HT3 receptors.

So it’s got activity on two of our target pathways. Awesome! What’s not to love? Well, there’s this little thing about dystonic reactions (including the generally irreversible tardive dyskinesia). Metoclopramide also tends to cause a lot of diarrhea. This is expected, since we actually use the drug as a prokinetic (i.e. to get your GI tract moving). But many chemo agents also cause diarrhea, and we need to be careful not to dehydrate our patients.

With the advent of newer agents, metoclopramide has fallen a bit out of favor. However, it still has a role in therapy for patients with refractory nausea, especially if they have impaired GI motility (think opioids).

And so, we come to the phenothiazines (that’s right, you may also remember these as the typical antipsychotics). They have surely stood the test of time - prochlorperazine (Compazine) and promethazine (Phenergan) go way back to the 1950s. In addition to the standard PO and IV dosing options, both can also be given IM and PR, which is super dang convenient for our patient who can’t keep anything down.

The main issue with these is that they are dirty drugs. Phenothiazines block D2 receptors in the CTZ but they also don’t discriminate against serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, or muscarinic receptors. You may see sedation and you may see orthostasis. Although it’s not typical at the doses we use for CINV, patients may also develop extrapyramidal effects (EPS) or akathisia. Sound familiar? Yeah, not a good idea to give these with metoclopramide. Not to mention, dopamine antagonists also carry the risk of QTc prolongation. Major DDI!

OK. There’s one more we can’t forget about. It’s our friend, olanzapine (Zyprexa), the atypical antipsychotic. It has some compelling data - check it out! Previously, olanzapine was already being used for breakthrough or refractory CINV. This study showed us that we could use olanzapine for prevention of CINV, specifically when used in a four-drug regimen in combination with a 5-HT3 RA, dexamethasone, and an NK1 RA.

However, olanzapine is not a benign drug, either. Among several other receptors, it blocks histamine, which can lead to some gnarly metabolic effects, such as glucose dysregulation and cholesterol elevations. It can also cause significant weight gain. Like the dopamine antagonists, it can also cause sedation and QTc prolongation.

The thing about those side effects, however, is that they are dose dependent. Olanzapine 10 mg is the “standard” dose that we’ve used for ages…can we go lower? A recent study looked at olanzapine 5 mg vs 10 mg in a four-drug regimen. The data suggests that we can probably get away with using the lower dose of olanzapine to minimize side effects, while maintaining antiemetic activity.

Counseling point: before your patient googles olanzapine, you may want to pre-emptively explain that you don’t think they’re having a psychotic break.

We can also look at when our patients should take olanzapine. Since we’re using it for prevention of CINV (typically given daily x 4 days), why not give it at bedtime? That way we can use the sedative effects to our advantage, and we don’t have to worry about our patients being zonked out of their minds during the day.

You’ll even see some practitioners dose olanzapine as low as 2.5 mg QHS x 4 days for elderly patients (or for patients who are particularly sensitive to the sedative/anticholinergic effects). Even at that low of a dose, it anecdotally appears effective for many patients.

Noticing a theme here? Several of the first-line antiemetics are known perpetrators of a prolonged QTc interval. We’ve got all of the 5-HT3 RAs (with an asterisk by palonosetron), and all of the dopamine antagonists. Throw in some CYP3A4 inhibition from the NK1 RAs, and we’ve got a potential scenario on our hands.

Because of the cardiac risk of these agents, it is prudent to obtain a baseline EKG, especially if other QTc prolonging agents are on board, or if the patient has risk factors for a prolonged QT at baseline. Be especially careful when the patient’s chemo regimen also prolongs QTc. Arsenic trioxide is a famous offender here. It’s got an intense dosing schedule, it’s moderately emetogenic, and it’s got a black box warning for QT prolongation.

Before moving on from dopamine antagonists, let me just say one more thing to put it all into perspective. Yes, there is a risk of weight gain, EPS, and a whole host of nasty side effects with these drugs. But we aren’t usually giving them around the clock for long periods of time. When patients take 10 mg of olanzapine daily for months, they may gain weight. When they take 5 mg for four days, it’s not likely to be that big of a deal.

Benzodiazepines

Are you surprised? Add anticipatory nausea to the list of things benzodiazepines (BZDs) are used for. BZDs are not “true” antiemetics, but due to their anxiolytic properties, they’re great for anticipatory nausea.

Some patients have such a rough time with CINV that they develop a Pavlovian response and can feel nauseous by certain triggers…even if they haven’t received any chemo. These patients might get nauseous in the car on the way to treatment, or from the smell of the infusion center as they walk in. Even seeing their infusion nurse in the grocery store could set them off.

Anticipatory nausea is best treated with fast-acting benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam 0.5-2 mg the night prior to chemo, and 1-2 hours before chemo. Why Ativan? We want a short half-life and most of our data is with lorazepam in combination with 5-HT3 RAs and dexamethasone. But you could use alprazolam, too.

Before I forget...remember metoclopramide? Well, as we know, it can cause some agitation, and guess how we treat that? Benzodiazepines.

Other Agents for CINV

Not that they are any less important, but there are a couple tricks we have up our sleeve when it comes to specific cases of CINV.

Occasionally, you will have a patient who has vertigo or gets nauseous when standing up/walking. The answer: anticholinergics. A scopolamine patch should do the trick. Pro tip: make sure you counsel patients to avoid touching their eye after handling the patch (unless they want some really dilated pupils).

Other anticholinergics you can consider are meclizine or dramamine. Meclizine is less sedating, but it is dosed more frequently, so pick your poison. Regardless, make sure you counsel your patient on anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, sedation, urinary retention, etc.).

Last, but not least, are the synthetic cannabinoids. Dronabinol and nabilone are approved for refractory CINV when patients have not responded to conventional treatments.

Dronabinol is available in an oral solution and a capsule, but they are NOT bioequivalent. The solution has greater oral bioavailability and so 2.1 mg oral solution = 2.5 mg capsules. Also note that both the capsules and the oral solution should be stored in the fridge (though the solution is stable at room temp for 28 days once opened).

FYI, increased appetite is not uncommon with these agents, but we can take advantage of this in patients that are nauseous and also having a hard time eating, or are underweight.

Applying to Practice: CINV Treatment and Prevention

Really, we’ve talked about a lot here. Let’s tie it all together.

There are 2 “main” sources of CINV Guidelines in oncology, NCCN and ASCO. NCCN is updated way more frequently, and is the gold standard that insurance payers look to when determining the appropriateness of a chemo regimen (i.e. determining whether or not they will pay for it). All that to say, we are going to focus on NCCN for our discussion.

While I won’t fully regurgitate the CINV guidelines, I’ll give you a high-level overview to help you make sense of it all. The first piece to this puzzle is knowing which anticancer agents/regimens pose the greatest risk for CINV, and which ones really aren’t a threat. NCCN breaks them down as such:

High emetic risk (≥90% frequency of emesis) - typically your cytotoxic “traditional” chemotherapy agents in high doses such as alkylators, anthracyclines and platinums

Moderate emetic risk (30-90% frequency of emesis) - pretty broad list, but these include lower doses of cytotoxic chemotherapy, high-dose methotrexate, and topoisomerase inhibitors (e.g., irinotecan)

Low emetic risk (10-30% frequency of emesis) - will be more targeted therapies (e.g., monoclonal antibodies and antibody drug conjugates), taxanes, and antimetabolites (e.g., standard methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, pemetrexed)

Minimal emetic risk (≤10% frequency of emesis) - these are almost exclusively monoclonal antibodies, but you will find some classic cytotoxic agents such as the vinca alkaloids and bleomycin

If you’re studying for the NAPLEX or a BCPS exam, I’d focus on learning a few of the agents that are high risk and a few that are minimal. That way, you’ll have an easier time picking the correct CINV regimen from the multiple choice list.

We actually do this for you in our Oncology Cheat Sheet, so check that out if you’re interested.

You probably don’t need to get in the weeds of low and moderate risk regimens unless you’re an oncology specialist.

Here are a few general rules to help you out:

If you see cisplatin or dacarbazine, it is a highly emetogenic regimen

Most monocolonal antibodies (end in--mab) are minimal emetogenic potential. You won't usually pre-treat for nausea, but you may pre-treat for infusion-related reactions (think tylenol, benadryl, +/- a steroid)

Almost everything else falls somewhere in between. Higher doses equal more potential for emesis (ex. cyclophosphamide)

The more chemotherapeutic agents in a regimen, the greater potential for CINV.

The chemo-induced nausea and vomiting guidelines are pretty straightforward, but as a general strategy we add agents in a step-wise manner based on the emetogenic potential of the chemo regimen. As we increase the emetogenic potential, we start adding multiple CINV agents with different mechanisms.

So, for a minimal emetogenic regimen, you probably won’t give the patient anything. As you move up to low-emetogenic potential, you might give the patient a prescription prn ondansetron or maybe a single IV dose of a 5-HT3 RA or dex 30 minutes before chemo.

Things get a little more complicated with moderate-emetogenic potential. I mean, look at that range. 30 - 90% frequency of emesis?!? It’s very difficult to make a one-size fits all approach to CINV prevention with that. Some practitioners informally break this list into “low-moderate” (30 - 60%) and “high-moderate” (60 - 90%) to make more CINV prevention a bit easier.

Regardless, with a moderate-emetogenic chemo regimen, you’ll be looking at pre-treating with a 5-HT3 RA and/or dexamethasone. You could even add an NK1 inhibitor if the patient experienced nausea with the last cycle, or you could add it up front if you’re giving a chemo regimen thats on the “high-moderate” side. If there is any risk for delayed nausea (and there usually is with those “high-moderate” regimens), then the patient should be given 3 days of dex. You could also consider adding 4 days of olanzapine.

For highly-emetogenic regimens, it’s pretty much a lock that you need to include all of our “Big 3” classes of agents (5-HT3 RA, dex, and NK1 inhibitor) and you’ll need prophylaxis for delayed nausea. We give these patients 4 days of dex (as opposed to just 3 days in moderate-emetogenic regimens). Olanzapine is also an option here.

The current NCCN Antiemetic Guidelines give you a lot of options to let you tailor your approach to your specific patient. There are CINV regimens that avoid NK1 inhibitors, for example, so you avoid CYP interactions if necessary.

The key is to remember the golden rule, that CINV is easier to prevent than it is to treat. Approach each patient and each scenario individually. There isn’t a single “best” strategy that works in all situations. Make the best CINV regimen based on your patient’s risk factors, drug interactions, lab values, performance status, and preferences. And then adjust as necessary (and you will need to adjust sometimes).

Just because your patient got nauseous on cycle 1 of FOLFOX doesn’t mean they need to be nauseous for the remaining 11 cycles. Tweak their prevention regimen a bit and try to make their next cycle more tolerable.

What oral cancer treatments? Is there any risk for nausea? What about the tyrosine kinase inhibitors?! Don’t worry, there’s a whole section dedicated to oral therapies. Oral anticancer agents are categorized as either moderate to high (≥ 30% frequency of emesis) or minimal to low (≤ 30% frequency of emesis).

Tables including relative emetogenic potential of all IV and PO agents are housed in both the NCCN (consensus-based, updated several times a year) and ASCO (evidence-based, updated periodically) antiemetic guidelines.

Clear as mud?

I can’t guarantee your patient will be as happy as Stanley on Pretzel Day, but you’ll definitely improve their quality of life if you can help them be one step ahead of their nausea.

Go forth and conquer, you CINV master. You’ve got this!

BTW - We compiled ALL of our Oncology Supportive Care posts into one handy, downloadable (and printer-friendly) PDF. You can get your copy of it here.