An Introduction to Pharmacotherapy for Multiple Sclerosis

Steph’s Note: In light of my early 2020 career change, I’m taking you all with me on my journey into the world of neurology and multiple sclerosis (MS). Given I’m relatively new to both the outpatient world and MS (and definitely new to the specialty pharmacy world), this is reeeeally a beneficial post for all of us. (They say it’s a higher level of learning to be able to teach others, right?) Hopefully you’ll learn a little about a disease state not usually covered in the normal pharmacy school curriculum, and I’ll research and deepen my MS knowledge for clinic!

And BTW - This post covers a lot of ground. If you’d like a downloadable (and printer-friendly) copy of it, you can get the PDF here.

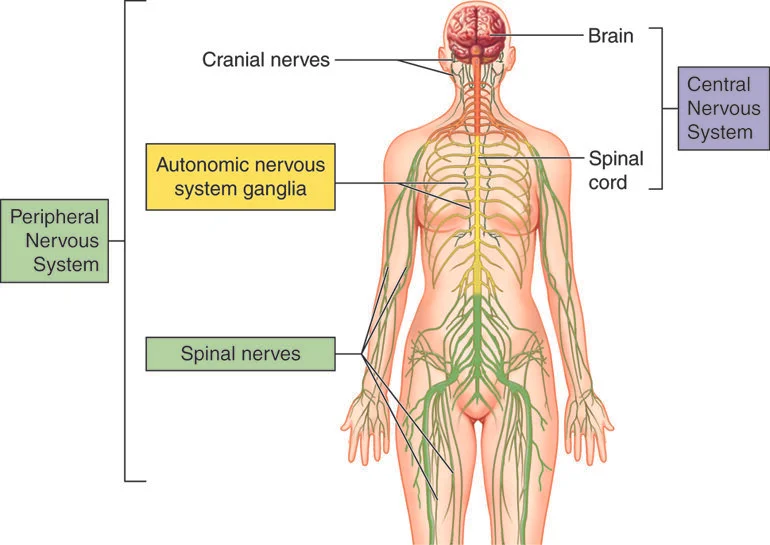

The human nervous system (Image)

What is Multiple Sclerosis?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurological disorder that results from a person’s immune system causing impaired neuronal communication. Neurons are specialized cells in the body that transmit electrical impulses to carry messages. The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system includes all the off shoots. (The nervous system is essentially an uber complex electrical circuit.)

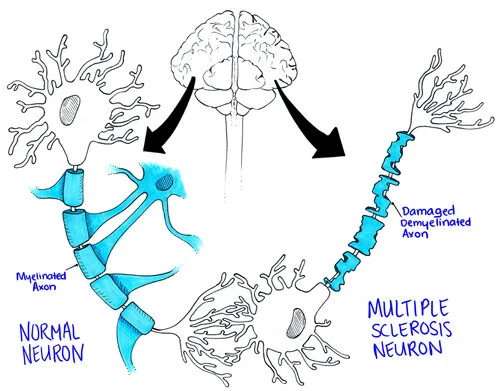

Neurons are able to conduct electrical signals in part due to their “insulation”, made by special cells called oligodendrocytes. This insulation is known as the myelin sheath, and its job is to ensure the integrity and delivery of transmitted electrical signals.

Mess with the oligodendrocytes, and the myelin sheath may not be made appropriately to begin with.

The normal neuron has its nice beads of myelin that allow signals to propagate along the axon, but the MS neuron doesn’t have the same insulation to protect signals. So the message doesn’t quite travel the way it should. (Image)

Mess with the myelin sheath, and the electrical signals may not arrive correctly - or at all. This can affect signals within the brain as well as those that are leaving the brain heading for other more remote destinations.

Mess with the myelin sheath, and the underlying tissues also become more vulnerable. This includes the actual nerve fibers.

You can think of neurons kind of like an electrical extension cord. Works great when it’s brand new, but if it develops cracks in the orange rubber outer shell or part of that shell comes off, your Christmas tree just may not light up reliably…

So what causes the damage to the oligodendrocytes and/or myelin sheath?

In the case of MS, it’s a patient’s own immune system!

We really don’t know for sure what triggers the immune system’s attack on a patient’s own myelin, but there do seem to be associations with both nature (aka genetics) and nurture (aka environmental factors and infections).

What's the Impact of Multiple Sclerosis?

We can think about impact in two different ways: quantitative and qualitative.

With regards to numbers, it’s estimated that almost 1 million people in the US are living with MS. Until this study was published in 2017, previous estimates were about half that. Not a good surprise. But it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s increasing in incidence, perhaps we’re just getting better at detection than in past days.

Speaking of incidence, because sound estimates have been really hard to come by until this landmark 2017 publication, it’s difficult to pin down how many people are developing MS each year.

More numbers: MS is usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years, and it’s far more common in women than men. Interestingly, there are also geographic patterns with the highest numbers in the northeast and midwest portions of the US:

(Image)

Weird, right?

It’s these kinds of numbers that have led to causal theories about sun exposure and vitamin D levels as well as hormones. Other possible (but unproven) risk factors include smoking, obesity, and certain infections like Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and measles. Epidemiological studies are ongoing.

Qualitatively speaking, MS’s impact on a person’s life has a wide spectrum of symptoms and progression. Common symptoms are related to impaired nerve signaling and can include weakness and fatigue, vision changes (blurred vision or diplopia possible), cognitive and psychiatric changes like memory impairment and depression, decreased coordination and balance issues, and bowel/bladder/sexual changes.

In more advanced stages, MS can lead to difficulties breathing, impairment of speech and swallowing, seizures, hearing loss, and tremors. But even though MS can be fatal in some cases, usually life expectancy for the majority of patients with MS is about 7 years less than the general population.

Kudos to the growing number of treatments and disease management strategies!

What are the Different Types of MS?

Trying to decide what kind of MS a person can be very, very difficult. In an attempt to make this more clear, the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of MS released clarifying definitions for 4 subtypes of MS in 2013.

But first, we should mention Radiologically Isolated Syndrome (RIS). These patients have no clinical signs or symptoms of MS. Evidence of demyelination is identified on brain or spinal cord imaging (MRI), often incidentally when the patient is scanned for some other reason (like migraines). RIS isn’t actually a subtype of MS, and although maybe it helps to think of RIS as “pre-MS”, that’s not necessarily quite right either since not all of these people always develop MS. (It’s estimated that over 50% of patients with RIS will be diagnosed with MS in the following decade.)

So now the MS phenotypes:

Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS): This is a patient’s first occurrence of MS-neurological symptoms that last at least 24 hours. But this isn’t actually an MS diagnosis either! Just because a person has one of these episodes does not necessarily meet criteria for a full MS diagnosis, although CIS patients who also have MRI evidence of damage often experience a second event that then leads to diagnosis of MS.

Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS): This is the most common MS phenotype when patients are initially diagnosed (~85% of patients). It is characterized by periods of symptomatic attacks (the relapses) interspersed with recovery periods (the remissions). Some patients recover fully after a relapse, whereas others do not, which can lead to worsening function and disability over time.

Secondary Progressive MS (SPMS): This type of MS follows an initial RRMS course. It is often described as progressive decline in function with or without associated relapses. (Yes, it IS confusing to differentiate this type from perhaps partial recovery from a relapse in RRMS. Thank goodness we pharmacists don’t do the diagnoses!)

Primary Progressive MS (PPMS): This is the less common initial presentation of MS (~15% of new diagnoses). It is characterized by disability progression from the initial onset of symptoms, without defined relapses to explain the disability accumulation.

Occasionally, you may run across a denotation of Progressive-Relapsing MS (PRMS). This is an older term that was supposedly phased out with the updated definitions, but some clinicians still use it. It’s perhaps best described as PPMS with episodes of relapse. So progression from the very beginning of onset of symptoms but also acute attacks thrown in as well.

For you more visual folks, check out the time vs. disability accumulation graphs to the left depicting MS types 2-4.

Pharmacotherapy for Multiple Sclerosis

Disclaimer: This is going to be a broad overview of the medications available for targeting the MS disease process. There simply isn’t enough space on this page to get too detailed given how many therapies exist at this point! We’re also not going into symptomatic therapies here either - that would be a whole other post (perhaps stay tuned in the future).

Now it’s possible this is going to make me sound super old, but when I was in pharmacy school, I don’t even think we had an MS lecture. And when I started this MS clinic job earlier this year, I was really trying to figure out why I had this large fuzzy area in my pharmacotherapeutic knowledge. Well, here’s why:

This timeline took me way too long to create. The pharmacy type A issue kicked in big time.

Considering I graduated pharmacy school in 2011, I decided not to feel quite so badly about my lack of familiarity with the majority of these drugs. But after I absolved myself of the pharmaceutical sin of not keeping abreast of this clearly hot growth area in the past decade, I immediately guilt tripped myself into learning as much as possible in a short amount of time! (And my learning continues - every day.)

So I’d like to give you the rundown on these therapies so that, even if you’re not practicing in neurology or MS specifically, perhaps you’ll know a little something about these medications when they pop up on your internal medicine admission’s home list.

There are many different ways to look at these therapies, also known as Disease Modifying Therapies (or DMTs). Sometimes we think about them in terms of level of efficacy in terms of preventing MS relapses (usually studied as relative decreases in annualized relapse rate or ARR) or MRI lesions. Other times we think about them in terms of how well they prevent patients’ disabilities from worsening (reductions in confirmed disability progression or CDP). Sometimes we think about them in terms of how they’re administered. Sometimes it’s useful to think about them from an adverse event perspective.

For the purpose of this post, we’ll think about them in 3 big buckets: home injectables (until very recently, these were “the older MS therapies”), the oral medications, and the infusions. This is probably my pharmacist brain kicking in here thinking practically, but don’t worry, we’ll talk about efficacy and adverse effects too.

Baseline Assessments Prior To Starting an MS Medication

I’m not trying to create a one size fits all approach here because each medication definitely has its own nuances. However, there are a few core labs that it may be prudent to check prior to initiation of any MS DMT. Even if the lab is checking for something that may not be a big deal with the specific current DMT choice, it’s very possible patients may switch therapies in the future. So it often helps to have these already on file.

Complete blood count with differential: We want to see the patient’s baseline absolute lymphocyte count. This can help to determine whether additional washout is necessary when switching between medications or what kind of infection risk we may be imposing on our patients when starting therapies.

Hepatic function tests (included in a comprehensive metabolic panel): Many of the medications undergo hepatic metabolism, so we need to check that they will be metabolized appropriately. Alternatively, many DMTs can cause hepatotoxicity, so it’s a good idea to have a baseline for trending purposes.

HIV screen: Many DMTs either modulate or suppress the immune system as their mechanism of action. Don’t really want to uncover a hidden infection after you’ve started suppressing the immune system.

Hepatitis B and C screen: Ditto for not wanting to find out about latent infections after a patient becomes immunosuppressed. Additionally, several DMTs carry a risk of hepatitis B reactivation, so we need to determine a patient’s status and need for treatment beforehand. Plus, how can one assess for liver dysfunction without screening for hepatitis? The liver function tests aren’t necessarily the whole picture, unfortunately. And finally, you just might run across someone who could benefit from hepatitis B vaccination, which may be a good idea to start before initiating an immunomodulator/suppressor.

Quantiferon gold: Ditto on uncovering and addressing latent infections beforehand. Don’t want TB hiding out…lurking…waiting for the right moment to rear its ugly head.

John Cunningham Virus (JCV) antibody titer: JCV is a ubiquitous virus that most of us have been exposed to at some point. However, in combination with certain DMTs +/- additional immunosuppression or disease states, JCV can increase risk of a fatal brain infection called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Screening ahead of time allows for risk stratification with certain DMTs and/or may even rule out certain therapies as too high of a risk.

Varicella virus antibody titer: Varicella is the virus responsible for chicken pox and (in its later phases) herpes zoster, or shingles. Multiple DMTs carry a risk of herpes zoster if patients are not adequately protected, so it may be prudent to check a patient’s chickenpox and/or shingles vaccination history in addition to checking the virus titer. Once a patient has been started on a DMT, vaccine response may be attenuated and achieving adequate protection may become more difficult.

Pregnancy test: There’s not much data for any of the DMTs in pregnancy, and several have outright contraindications due to teratogenicity. When encountering female patients of childbearing age, we pharmacists should be assessing for contraceptive modalities, history of hysterectomy, or asking for a pregnancy test.

Now that we’ve discussed some of the useful baseline assessments, let’s talk about the meds. One thing to remember with all of these therapies is that they are meant to prevent or lessen future damage. None of them can reverse damage already done.

Home Injectables for Multiple Sclerosis

Until a couple of weeks ago, this category really only included glatiramer and interferon products. Let’s take these one at a time, and then we’ll discuss the new kid on the block.

Glatiramer

Glatiramer is a mildly efficacious DMT indicated for relapsing forms of MS only (not PPMS). According to the 2018 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) MS guidelines, in clinical studies comparing glatiramer with placebo, glatiramer decreased annualized relapse rates (ARR) by ~20%, but that difference wasn’t really seen when compared with interferon. It also didn’t show a big difference on confirmed disability progression (CDP).

There are 3 different glatiramer products on the market: brand name Copaxone, the branded generic Glatopa, and then generic glatiramer acetate. They are all versions of the same amino acid concoction: glutamate, lysine, alanine, and tyrosine.

I know, *gasp* that there’s a drug name that actually makes sense, right?!

The idea behind this amino acid primordial soup is that it mimics myelin to block T cell attack by the patient’s own immune system. Regardless of which product is chosen (or required by insurance…), they are all subcutaneous injections administered either daily or three times weekly by pre-filled syringe or auto injector.

If you’re not familiar with auto injectors, let’s just say that, while I’m sure the drugs took a lot of R&D to develop, these devices had to have had armies of developers as well. For example, check out the Copaxone Autoject 2 to see how these types of devices may help nervous patients avoid the needle. (Of course, they often also come with 5 million steps to learn the injection process, but for some people, it’s worth it not to have to play darts with prefilled syringes and their abdomens.)

So why use these often complex injection devices for a medication that has perhaps a modest effect on MS relapses?

There is no required routine monitoring. And that is very attractive for some people.

Lipoatrophy in the thigh after glatiramer injections. (Image)

In general glatiramer is pretty well tolerated. Although almost all patients experience some type of injection site reaction (redness, itching, etc), they’re not usually severe or long-lasting. Some patients, however, may experience a benign (but anxiety-inducing) immediate post injection reaction that happens seconds to minutes after administration. This syndrome can present as flushing, increased heart rate, and even transient chest pain, but it shouldn't last more than about 15 minutes.

Doesn’t mean it doesn’t scare patients! Counseling is imperative, especially since this post-injection reaction often occurs at least a month into therapy.

The other important counseling point with glatiramer is to rotate injection sites. Over time, patients can experience lipoatrophy and/or skin necrosis, which can be permanent and disfiguring.

Interferons

There are 2 main classes of interferons used in MS: interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b. It’s not entirely understood how these medications work in MS, but through interferon’s activity in cell signaling cascades, they are thought to decrease T cell activity.

Check out the below chart of available interferon products, but also know there are some common themes with all of these…

SC = subcutaneous; IM = intramuscular

For all of these, it’s pretty much recommended to start at a low dose and titrate up to full dose over the course of several weeks (usually 4-6 weeks).

They can all cause elevations in liver function tests (LFTs), reductions in lymphocytes, and changes in thyroid function. Lab monitoring is required.

There is some concern for worsening psychological illness, including depression and suicidal ideation. Perhaps not an outright contraindication, but consideration should be given to a patient’s mental status and monitoring if these are chosen.

They can all cause flu-like symptoms, usually about 1 day after injecting. This includes headache, fatigue, chills, and body aches. Use of acetaminophen on treatment days may help. These reactions do usually improve with continued use.

Interferons are considered to be of moderate efficacy with reductions in ARR of ~20% compared with placebo. They also reduced CDP by about 30%.

Ofatumumab

This is the exciting new kid on the DMT block! Approved in August 2020, ofatumumab (Kesimpta) is a recombinant human monoclonal antibody targeted at the CD20 molecule on certain types of B lymphocytes. It’s binding leads to antibody-dependent cellular cytolysis and complement-mediated lysis of those B cells.

If this anti-CD20 mechanism sounds familiar, there’s a reason for that. The mechanism of ofatumumab isn’t exactly all that novel given there are other anti-CD20 drugs on the market, and some are even used for MS (more later). Ofatumumab itself has actually been on the market for several years now (as Arzerra) and is used for chronic lymphycytic leukemia. So what’s the big deal?

Home administration, my friends!

Ofatumumab is the first at-home, self-administered anti-CD20 therapy. (When we get down to the other anti-CD20 therapies (because we will), you’ll get why this is such a huge deal.)

The Kesimpta Sensoready autojector is given subcutaneously 3 weeks in a row as a loading dose, and then it’s one monthly injection thereafter. Counseling points include the possibility of an injection reaction, mostly with the first dose, that often includes headache, tachycardia, dizziness, abdominal pain, and flushing. While >99% of both the systemic and local injection reactions experienced were mild and self-limiting, it’s also important to know that premedication with steroids, antihistamines, or acetaminophen did NOT help to prevent the reaction.

So that’s unfortunate. But not a deal breaker.

Ofatumumab is a highly efficacious medication. It reduced ARR 55%, CDP 34%, and radiologic lesions by up to 85% compared to teriflunomide (whoa - an active comparator, not placebo! Finally!). It rapidly depletes B cells below the lower limit of normal in 95% of patients within 2 weeks of starting the medication, and if patients need to discontinue ofatumumab, B cells replete to above the lower limit of normal ~23 weeks after the last dose.

Log that away. Ofatumumab is a pretty quick onset and relatively fast offset of effect.

So those are the home injectable options for MS. We’ve certainly come a LONG way from just glatiramer!

Oral Medications for MS

If you can, take a moment to revisit the above DMT approval timeline from earlier. See Gilenya on there, approved in 2010? That was the first oral medication approved for MS. This was only a mere 10 years ago and seventeen years after the first approved interferon (Betaseron) in 1993.

It’s important to remember that many patients with MS waited a long time for therapeutic options that didn’t involve needles.

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Modulators

This group is the “S1Ps”. It includes 3 family members at this point: fingolimod (Gilenya), siponimod (Mayzent), and ozanimod (Zeposia).

Unless you were doing extra credit in biochem, I’m willing to bet that you (like me until a few months ago) have never heard of S1P receptors. So let’s take a little side trip.

Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a lipid messaging molecule. It binds to its G-protein coupled S1P receptors, which leads to impacts on a plethora of processes, including inflammation, neuro and cardiac development, vascularization, etc.

There are 5 different S1P receptor subtypes, creatively dubbed S1PR1-5. These S1P receptor subtypes are expressed in varying levels in multiple tissue types. Even within just the immune system, expression of S1P receptors on particular types of cells varies. Check out the below summary chart about the 5 subtypes of S1P receptors and their normal downstream effects.

(Image)

So you can imagine that as drug targets, it gets a little messy if we affect more types of S1P receptors than just those involved with the immune system cells we want to shush. This is the case with fingolimod.

Fingolimod was the first of the S1P-receptor modulators, and it’s pretty nonselective. It modulates the function of S1PR1, 3, 4, and 5. Checking out the locations of these receptors in the chart here, you can see why some of the downstream effects of this medication include decreased egress of lymphocytes from lymph nodes (keep those overactive immune cells corralled - this is actually the mechanism for use in MS), impacts on white blood cell migration (also desirable), and bradycardia and AV node conduction issues (whoops, collateral damage).

Because of its non-selectivity and potential cardiac effects, patients starting fingolimod have to undergo an FDO, or first dose observation, when starting or resuming this medication after being off for more than 2 weeks. This means patients are directly observed by a nurse for about 6 hours after taking the first capsule, with periodic EKG and vital sign monitoring. This may be done in a clinic setting, or given recent changes with COVID, in the patient’s residence with a home nurse.

Fun fact: fingolimod is the only DMT approved for pediatric MS in patients as young as 10 years old.

Anyways, so of course the race was on to develop a cousin medication that had all the benefits and efficacy of fingolimod without those annoying and potentially dangerous adverse effects.

Enter siponimod.

Rather than binding to the majority of S1P receptor subtypes, siponimod is selective for S1PR1 and 5. Right there, we cut down on the possibility of quite so many cardiac effects, which is why siponimod does not have an FDO requirement. Of course, you can see the S1PR1 does still live in cardiac tissue, so you would still want to choose your candidates carefully and investigate any history of cardiac disease. But logistically, life just got WAY easier.

However, there’s a catch. Although siponimod alleviated the FDO problem, it came with its own baggage - pharmacogenomic metabolism variations. Because it is extensively metabolized (~80%) by CYP2C9 and there is wide variation in that particular enzyme’s activity across populations, patients may require different doses depending on what CYP2C9 alleles they express. Patients who are CYP2C9*3/*3 actually should not receive siponimod at all! So patients have to undergo CYP2C9 genetic testing prior to starting siponimod.

Luckily, the manufacturer covers the cost of the lab test (genetic testing = $$), but it’s still one more logistical hurdle to assess before patients can start their therapy.

Enter ozanimod.

Ozanimod was approved in March 2020 and, like its cousin siponimod, is selective for S1PR1 and 5. However, rather than being metabolized almost exclusively by CYP2C9, it goes through a series of enzymatic transformations to active metabolites. So no need for genetic testing before determining patient eligibility and dosing. But (of course there’s a but) it does carry precautions about concomitant use with serotonergic medications and tyramine-containing foods like aged cheeses or cured meats. So it didn’t get off totally free of risk either.

Speaking of risk, other things to note about the S1Ps include… Possibility of macular edema. Patients should have a baseline eye exam and periodic monitoring. Cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and herpes zoster (shingles) are possible, and patients do carry a higher risk of infections in general on these medications. Liver function should be regularly monitored. That being said, they are moderately efficacious, with decreases in ARR of ~45-55% compared with either placebo or interferon and reductions in CDP of 20-30%.

And the last VERY IMPORTANT note about S1Ps. If patients have to discontinue these medications, it’s important to ensure the gap between this and the next therapy isn’t too long (generally no longer than 8 weeks) because discontinuation has been associated with a rebound syndrome, in which patients experience a worsening and often more severe exacerbation of MS symptoms.

Fumarate Derivatives

There are 3 medications in this class as well (well, technically 4, if you count a generic version becoming available in late 2020). We have dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera and generic both now available), diroximel fumarate (Vumerity), and monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam).

All of these fumarate derivatives are thought to activate the nuclear factor-like 2 (Nrf2) pathway, which may lead to anti-inflammatory effects and cell protection. But it’s not really well-described. Just remember that the Nrf2 pathway seems to help cells deal with oxidative stress.

Maybe we all need a little more Nrf2 stress relief in our lives, amiright?

Ok, different kind of stress.

Anyways, there are 4 medications available in this class, but really, they all end up being the same pharmacologically active entity: monomethyl fumarate (MMF). Tecfidera, generic dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and diroximel fumarate all undergo rapid esterase hydrolysis to MMF. Interestingly, all 3 of the “me too” meds, generic DMF, Vumerity, and Bafiertam, were approved based on Tecfidera’s clinical trials and being “biosimilar”.

So how to choose between them? And why one instead of another?

All are dosed twice daily. All require an initial dose titration. So improved dosing frequency isn’t the answer.

Yes, this dog and I DO love peanut butter. (Image)

Well, Tecfidera was the first in the bunch, and it (and its generic DMF) can have some nasty GI upset, including nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. The recommended dose titration is there to try to help with this, but it’s often not long enough for many people to acclimate. Taking Tecfidera with high fat and high protein meals (PEANUT BUTTER!!! or yogurt, if you’re being healthier) may mitigate those symptoms.

Patients also often experience significant flushing with Tecfidera/DMF. The food recommendation above may help the flushing as well, and many people “grow out of it” with time… But sometimes they don’t. Another possible mitigation strategy is to take Tecfidera/DMF with a baby aspirin 81mg daily, about 30 min prior to the first dose of the day. But again, sometimes this just doesn’t do the trick. Or maybe you don’t want your patients taking aspirin regularly due to other medical issues, especially if they have a history of GI problems.

Enter diroximel fumarate.

This version, which is basically a chemically modified dimethyl fumarate, was developed to lessen its predecessor’s GI adverse effects. In the EVOLVE-MS-2 randomized trial, diroximel fumarate led to significantly less GI adverse effects and reduced treatment discontinuation due to those effects compared with DMF. We’re pharmacists, we like adherence!

So then what about MMF?

For all my Parks and Rec peeps out there. (Image)

Literally the same deal as diroximel fumarate. MMF is thought to improve adherence and GI tolerability compared with DMF, according to this study.

So how well are all of these fumarate derivatives expected to work in MS? They’re pretty decent. They fall into a similar range as the S1P modulators with a moderately effective rating, with decreases in ARR of ~50% compared with placebo and reductions in CDP of ~40%.

In addition to the more immediately noticeable GI and flushing adverse effects, they too carry risks of PML and infections. Liver function monitoring is also important.

Teriflunomide

(Image)

Teriflunomide (Aubagio) is actually the active metabolite of leflunomide (Arava), which is a medication used in rheumatoid arthritis. Teriflunomide inhibits an enzyme called dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, thereby inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis. (Remember the pyrimidine building blocks are thymine and cytosine in DNA and uracil in RNA.) Decreased pyrimidine production ultimately leads to decreased proliferation of lymphocytes, which is thought to reduce the amount of auto reactive damage caused in MS.

Happily, teriflunomide is a once daily medication. It’s considered modestly effective with reductions in ARR of ~35% and decreases in CDP of ~25% compared with placebo. Teriflunomide is generally fairly well-tolerated, although one of the most common complaints is the hair thinning and loss that can accompany this DMT.

Remember, many MS patients are young females, and even though this is a purely cosmetic side effect that usually improves with time, how many of us want to deal with more hair on our sink counters and in our shower drains than we already do!?

Just ask my vacuum cleaner - it has a tough job.

Otherwise, monitoring for liver function is essential - and actually, we usually ask patients to have labs done every month for the first 6 months of therapy. This can be a bit burdensome for patients, but given the possibility of liver injury, it’s necessary.

#truestory (Image)

Another major note about teriflunomide is its teratogenicity. It is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy due to fetal risk. Unlike most medications for which we are only concerned about females and reproductive effects, both females and males of childbearing potential should use contraception while taking this medication! The reason for this is that teriflunomide is detectable in semen.

The good news is that if a woman or man wants to start a family, or if a woman finds out she is pregnant while taking teriflunomide, there’s a way to rapidly eliminate the drug from the patient’s body. Cholestyramine! (Yes, that same bile acid sequestrate used for hyperlipidemia.) It’s a 3 times a day for 11 days process and not very fun given the thick, goopy nature of this binding agent, but this washout has been shown to reduce teriflunomide serum concentrations to below detectable levels.

So at least there’s some sort of backsies reversal process available in case of a surprise!

The cholestyramine washout can also be used in the case of teriflunomide toxicity, but remember that cholestyramine has to be separated from all other medications in order to ensure their absorption. Other meds should be given at least 1 hour before or 4-6 hours after cholestyramine.

Cladribine

(Image)

So far, we’ve talked about oral medications that are taken on a continual, regular basis. But enter the game changer: an oral medication that is taken only in intermittent courses!

Cladribine (Mavenclad) was approved in 2019, and only requires a total of 20 days of therapy spread out over 4 months in 2 years. The dosing is weight-based and follows a schedule such as here:

Although it’s not fully known how cladribine works, what is known is that it is a purine nucleoside analog prodrug. When it’s activated, it incorporates into DNA and shuts down DNA synthesis and repair. This is thought to lead to a depletion of B (along with some T) lymphocytes, which then come back after the cladribine is gone - hopefully as nicer, less mercenary lymphocytes set on attacking a patient’s own myelin. This is why cladribine is considered an immune reconstitution therapy.

Lymphopenia is an expected side effect of this medication - that’s the whole point of its action; however, we don’t want patients to experience profound lymphopenia, which can put them at increased risk for infections and herpes zoster outbreaks. In general, the lowest lymphocyte counts (or nadir) are experienced about 2-3 months after starting a treatment course, so patients should be counseled about taking precautions against infections, especially during that time period.

Male and female patients should use contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose of each treatment course. Very important for family planning!

Cladribine is a moderate-highly effective medication with reductions in ARR of ~55-58% and decreased CDP of ~30% compared with placebo.

Infusions for Treatment of MS

Rituximab

RItuximab isn’t technically approved for use in MS, but we have years of off-label experience doing so. This chimeric (ahem, part mouse) monoclonal antibody has been widely used for a variety of conditions due to its anti-CD20 mechanism, and MS is no exception. Although you may recognize its mg/m2 dosing in other, usually oncologic, indications, patients with MS generally receive flat doses: 1000mg IV on days 1 and 15, then a maintenance dose of 1000mg every 6 months thereafter.

For some patients, every 6 months is just too long, meaning they become symptomatic due to B cell repopulation earlier than anticipated. It may be prudent in some cases to check a B cell panel to see what the CD20+ cells are doing at perhaps 5 months instead of waiting the full 6 month interval. If necessary, the dosing window may be shortened.

(Image)

Because it’s chimeric, rituximab carries a risk of infusion reactions, consisting of hypotension, bronchospasm, angioedema, itching, or even anaphylaxis. Premedication with steroids, diphenydramine, and acetaminophen is imperative.

Also, even though CD20 isn’t expressed on plasma cells (the part of the immune system that makes immunoglobulins that fight infections and induce vaccine responses), rituximab can have impacts in both areas. Immunoglobulin levels often decrease, and patients may be at increased risk of infections. Responses to vaccines may also be diminished, and if possible, vaccinations should be completed 4 weeks prior to rituximab initiation.

Ocrelizumab

Ocrelizumab is yet another anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, but this one is approved for MS. In fact, it is one of the few therapies approved for use in PPMS! However, its highly efficacious categorization mostly refers to the relapsing forms of MS, for which ARR was reduced almost 50% and CDP decreased ~30% compared to interferon. Reduction in CDP in PPMS was reduced by ~24% compared with placebo.

Unlike rituximab, ocrelizumab is a recombinant humanized version, which is thought to reduce the occurrence of infusion reactions and antibody formation against the drug. (But spoiler alert, infusion reactions still do happen, and premedication is still advised.) It also binds to a different part of the CD20 molecule, so it’s not exactly the same as rituximab. In order to ensure tolerance, the first dose is split in half before moving on to the full maintenance dose: 300mg IV on days 1 and 15, followed by 600mg every 6 months.

Much like rituximab, ocrelizumab may diminish vaccine effectiveness and increase risk of infections. Also like the other anti-CD20 therapies, hepatitis B reactivation is of concern, and hepatitis screening should be completed prior to therapy initiation.

Natalizumab

(Image)

Natalizumab (Tysabri) is its own beast and, after all this chat about various anti-CD20 antibodies, it’s refreshing to say it is in a class all its own.

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted against the alpha-4 subunit of integrin, which is a molecule that helps with adhesion and migration of leukocytes from blood vessels into the inflamed tissue. In MS, natalizumab’s effect is thought to come from halting T cell migration from the blood into the CNS.

It’s…the gatekeeper of the gatekeeper. (Cue booming, ominous music.)

It is a highly effective therapy for MS with reductions in ARR of almost 70% compared with placebo! CDP was also decreased over 40% compared with placebo. Impressive numbers, considering what we’ve discussed thus far, right?

But of course, there’s a catch. There’s always a catch.

Natalizumab also has a REMS program called TOUCH due to risk of PML. The three big pieces that seem to play a role in risk of PML are the following:

JCV titer

Time on natalizumab

Prior or concomitant immunosuppression

Higher titers, longer time on medication, and/or use of immunosuppression seem to increase risk of a patient developing PML. The TOUCH REMS program facilitates tracking of JCV titers, controls where the patient receives the natalizumab infusions, and keeps tabs on development of adverse effects, like opportunistic infections and malignancies.

Like the S1P modulators, natalizumab also carries a risk of rebound disease if doses are missed or time intervals between natalizumab and a new DMT are too long. Add to this that natalizumab is a monthly (or maaaaybe every 6 week) regimen, and you can see that it’s a commitment to be on this DMT.

Alemtuzumab

Last, but not least, we have alemtuzumab (Lemtrada). You may have heard of this medication under its other name - Campath - for oncologic indications. As Lemtrada, it is dosed as 2 intermittent courses over 2 years: 12mg IV daily on days 1-5 in year one and then 12mg IV daily on days 1-3 in year two. Regardless of indication, it is an anti-CD52 humanized monoclonal antibody that leads to antibody-dependent lysis of cells expressing the CD52 protein. These cells include B and T cells, monocytes, macrophages, NK cells, and some granulocytes too!

I love the Madagascar penguins so much. Yes, Rico, kaboom, kaboooooooom. (Image)

Alemtuzumab is kinda like the less discriminant bomb in the MS arsenal with possible high reward but also high risk. It is highly efficacious with a relative reduction in ARR of 50-70% compared with placebo, but this immune reconstitution therapy comes with its own costs.

There are four - count them, FOUR - black box warnings on alemtuzumab for MS:

Development of autoimmunity, including immune thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP) or anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease

Potentially fatal infusion reactions (MUST premedicate)

Stroke and cervicocephalic arterial dissection

Cancer

In addition to these boxed warnings, alemtuzumab can also lead to thyroid disorders and bone marrow suppression, which can lead to infections, including PML. Patients even take prophylactic acyclovir to prevent herpes viral infections. Basically the result of all of these possibilities is a mandatory REMS that requires all alemtuzumab MS patients to complete a total of FIVE YEARS (48 months after the last course of drug) of monthly lab monitoring!

Yeah, pretty intense, and definitely a commitment for patients.

Summary of Pharmacotherapy for MS

And there we have it! The landscape of current therapies for MS. Although it has drastically changed even in the last decade, there’s still so much work to do! Interestingly, many labs are investigating the possibility of remyelination to actually reverse damage - how cool is that!? But it is still a ways away, and in the meantime, we will use what we have.

One of the biggest lingering questions at this time is how to leverage this array of medications. Likely at least in part because there have been so many approved in a relatively short amount of time, we don’t exactly know what the best approach is for using them. Do we start with an aggressive therapy up front in hopes of preventing future damage and preserving functionality (at the cost of adverse effects), or do we start with a less efficacious but more tolerable therapy and escalate when/if the patient has a relapse or intolerance? Since MS often “quiets” in the older years, at what age do we discontinue DMTs entirely?

These questions are the foci of multiple clinical trials, so perhaps we will have more direction in the coming years about how to use the arsenal at hand.

Here’s to future research and additional learning!