The Ultimate Guide to HIV for Pharmacists (Reboot)

Editor's Note: Back in the day (can you believe we’re actually calling 2016 “back in the day”?), we wrote a 7-part series called "HIV Boot Camp." However, over the years, A LOT has changed in the management of HIV with new drug approvals prompting changes in the treatment guidelines.

We proudly present to you an updated summary of the HIV fundamentals, including a run down of each drug class to highlight what you need to know.

We've also made an HIV Cheat Sheet that covers basically everything you need to know about HIV pharmacotherapy. Be sure to check that out. It's a handy companion that will get you through your ID module, an APPE rotation, or the NAPLEX with ease.

Part I: HIV Background and Pathophysiology

Background

To say that a lot has changed in the world of HIV over the last few decades is a bit of an understatement.

What hasn’t changed? HIV is the worst. Let's just start right out with that.

Although it's thought to have been around for decades, it didn't really "arrive" on the scene in the US until the early 1980s, making its debut with pepperings of case reports of a very uncommon lung infection called Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), since re-named Pneumocystis jiroveci (PJP).

Anyway, since PJP typically doesn’t cause infection in healthy individuals, it was decided that whatever this is, it’s causing an immune deficiency. And since these mounting cases of PJP (and other opportunistic infections [OIs]) were fairly isolated to otherwise healthy men who happened to be homosexual, a super awesome and totally PC term for this new syndrome was born: Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID). Yep. That's what science decided.

Not long after that, fortunately a new term, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) was established, Tom Hanks won an Oscar, the Broadway musical "Rent" was made, and Magic Johnson defeated the virus with cash. Then we learned that AIDS was caused by a retrovirus, which eventually became known as named Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

But, as you know, the story doesn’t end there.

Eventually, we started developing drugs that completely flipped the script on HIV. What was once a death sentence in the 80s and 90s became the incredibly manageable chronic disease it is today.

And get this:

Back in 1996, the average life expectancy in a 20-year-old newly infected patient with HIV was 30. Fast forward to present day, based on data from a study published in 2013, the same 20-year-old patient started on treatment can expect to live into their early 70s. Take a moment to let that sink in.

Imagine where we are 10 years later knowing that treatment options for people living with HIV (PLHIV) have only become more safe, effective, and accessible.

The other side of the coin is there is still a ridiculous amount of stigma that surrounds HIV and the patient populations at risk. Sigh. A conversation for another time.

Pathophysiology

So what exactly does HIV do to the body?

From the patient's perspective, it goes a little something like this...

You're exposed and nothing happens for about 10 days. The virus exposure most likely came from either unprotected sex or IV needle sharing. But it can also be transmitted vertically (mother to baby).

Anyway, you're feeling fine and then all of a sudden, you're not. You have to leave work early because you've got a fever of 102 and you're all achy. Your head hurts. You're exhausted. Your face is flushed. There's a rash on your back and abdomen. Every time you swallow it feels like you're trying to get down a golf ball. You take Advil. It does nothing. You take Tylenol. It does nothing. You lay down on the couch and try to binge watch something on Netflix. But you can't focus. You throw up into the small bathroom trash can you placed by the couch. You have a hard time keeping down even Gatorade and sprite.

You try going to a doctor. They run an influenza test (if it's in season) and find that it's negative. They tell you that you probably have the flu anyway. They say to keep up your fluid intake and to try to eat a soft diet of soups and broths.

This goes on for weeks to months and you’re exhausted.

Finally (thank God) it gets better. You start to feel normal again. You're weak and dehydrated, but your appetite comes back. You go back to work. And after another few days or so you start to feel like your old self again. You finally resume your social life and everything is right in the world again. You go on about your life for a few years with no real restrictions.

Then things start getting weird. You feel like you're constantly getting colds. You've been losing weight gradually for a few months. You've had bronchitis 3 times this year. Last month, you had an ear infection out of nowhere like when you were a 6-year-old. Finally, on what feels like your 14th trip to the doctor, they take some blood and run some tests.

A day or two later, they call you and ask you to come into the office.

They sit you down on the exam chair with the disposable rolled out paper. And the provider tells you that you’re HIV positive. You are devastated and haven’t even had time to process this news when you learn that they want to start you on treatment right away. They run more tests on you. And you go home with a bottle of pills that you’re told you’ll be on for the rest of your life.

So what's happening in the story above?

Once in the body, HIV burrows its stupid little way into the cells of your immune system. Its favorite are CD4+ T lymphocytes but it doesn’t discriminate against macrophages or dendritic cells. Initially, HIV spends some time under the radar as it hijacks the host cell’s machinery and turns them into virus factories. Hence, why most patients are relatively asymptomatic when first infected.

Anyone else remember when Spongebob characters used to just…explode for no reason?

Eventually, the immune system catches on. It goes berserk for a few weeks launching every countermeasure it can think of.

The body eventually develops antibodies to HIV. This is called seroconversion, and it's what the poor patient above was going through for the past 2 or 3 weeks.

Then it enters a "clinical latency" phase that can last for years. Patients are asymptomatic, but behind the scenes their CD4 counts are steadily dropping at a rate of about 200 cells/ml per year. Meanwhile, the number of HIV copies in the blood is steadily increasing. On a graph, it looks something like this:

Eventually, CD4 counts drop so low that strange diseases (like PJP) that don't typically infect healthy people start cropping up. At this point, we say that the patient has progressed to Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) as a result of their HIV infection.

If left untreated, the patient will eventually succumb to an infection that they just can’t bounce back from because they literally have no immune system to fight it.

So what’s a retrovirus?

It’s not a fancy, bell-bottom-wearing virus with an afro, that’s for sure.

Retroviruses, by definition, convert RNA into DNA. That’s right, they literally break the central dogma of DNA to RNA to Protein. How does HIV do this? With a little enzyme called reverse transcriptase (RT), that’s how!

The thing about RT is that unlike DNA polymerase, it has no proofreading ability. It’s incredibly error prone. Which you would think would be a good thing. You know, trying to treat a virus that can’t get its life together. But it’s actually the opposite. With this high error rate, mutations accumulate at an accelerated rate relative to proofread forms of replication.

Why does this matter?

Because a virus that mutates all the time is incredibly difficult to treat. This is why we’ve had no luck (to date) developing vaccines for HIV. It quickly gains resistance to a given drug or a regimen, especially when a patient is nonadherent.

Part II: Treatment Goals and Considerations

Alright. So now we've got the background and patho under our belts. We know what a retrovirus is and what it does on a molecular and phenotypical level once it enters the body.

We've also looked at a small glimpse of what a patient might experience in the early days of an HIV infection. So how do we help this patient?

Baseline Labs

First things first.

After confirmed diagnosis (with HIV antigen/antibody testing), we need to gather some baseline labs before we can start treatment. These also apply to modifying treatment because we want a good idea of where the patient is before we make changes to their existing regimen.

Here are the big ones:

HIV RNA viral load*

CD4+ T lymphocyte cell count

Genotypic resistance testing

Serologies for hepatitis B and C viruses

Basic metabolic panel (BMP)*

Complete blood count with differential (CBC w/ diff)

Lipid panel

Liver function tests (LFTs)*

HLA-B*5701 test (if abacavir is being considered)

*We’ll want to get these again 4-8 weeks out to make sure we’re trending in the right direction (and that, you know, nothing wacky is going on with respect to the patient’s overall health).

BTW, there's a lot deeper we can dig as far as lab work goes, but what we’re about to go over will cover the bases for most PLHIV.

HIV Viral Load

Viral load (i.e., number of copies of HIV RNA per mL of blood) is the most important marker of response to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

In case you were wondering, there’s no difference between ART and the original term, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). They can be used interchangeably. You’re just far more likely to run into the former, so we’ll be using it throughout. It makes sense, right? ART is shorter. And why would you administer an inactive antiretroviral treatment versus a highly active one anyway? I digress.

A patient’s viral load before and after ART initiation (or changes to an ART regimen) allows us to get a pulse on how treatment is going and if the disease is progressing or not.

What we aim for with treatment is viral suppression, which is clinically defined as a viral load of less than 200 copies of HIV RNA per mL of blood, although you’ll see other cutoffs throughout.

Eventually (we hope), the patient can reach undetectable viral load. This means the number of copies of HIV RNA in a mL of blood is so low that it’s below the limit of detection (typically 40 copies/mL for most standard lab tests).

By the way, reaching an undetectable viral load is a major milestone. Why? Studies show that PLHIV who are undetectable cannot transmit the virus. This is called the U=U movement. Undetectable = Untransmittable.

CD4 count

OK so we talked about the importance of viral load at initiation and throughout therapy. Getting a CD4 count is also crucial, especially at entry to care.

You may remember that CD4 is a specific receptor on some T-helper cells of your immune system and that HIV specifically targets these CD4+ cells. As the infection progresses, the CD4 count goes down. And as you probably guessed, without CD4 cells, we don’t have much of an immune system.

Since the CD4 count provides information on the overall immune function of a person with HIV, it’s particularly useful before initiation of ART to determine if OI prophylaxis is needed.

Though not to the same extent of viral load, CD4 count is also used as a measure to monitor response to therapy. If the viral load is decreasing and CD4 count is increasing, then our treatment is likely working. Let’s stick with the regimen.

If the viral load starts to creep up (which may or may not correlate with a decrease in CD4 count), however, then it's time to reassess therapy and maybe add OI prophylaxis…more on that later!

Genotypic Resistance Testing

OK, so say we’re seeing an uptick in viral load with a patient who previously had undetectable levels.

What could be going on here?

Well, as we mentioned before, retroviruses mutate A LOT. This leads to resistance to medications and treatment failures.

This especially becomes an issue when patients aren’t adherent to their treatment.

Why?

Not only does it suck for the patient because their virus is out of control, which puts them at risk for an OI, this person can then go and infect someone with that same awful, resistant virus.

For this reason, resistance testing is recommended baseline when first selecting an ART regimen and for ART-experienced PLHIV who are experiencing treatment failure.

In a nutshell, resistance testing primarily focuses on testing for mutations in two enzymes (one we already talked about) HIV uses in its evil scheme: reverse transcriptase and protease. However, if transmitted resistance to another HIV enzyme, integrase, is a concern (or if the provider would just like to be thorough in their initial workup), then a separate test for integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) resistance can also be ordered.

This is all you really need to know (and maybe even some you don’t), but if you’re interested, the nitty gritty details on drug-resistance testing can be found here.

Hepatitis B (HBV) Serology and Hepatitis C (HCV) Screening

Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for PLHIV to be co-infected with hepatitis.

HBV is the main one we’re looking at here because a lot of treatments for HIV are also used to treat HBV. So let’s kill 2 birds with 1 stone by selecting a regimen that covers both, right? However, if we do start a regimen that covers both HBV and HIV, it is SUPER IMPORTANT that our patients know to not abruptly discontinue treatment because it can result in a serious, life-threatening HBV flare. It’s a black-box warning.

To prevent this from happening, we have to know whether or not the patient is co-infected with HBV, right? So it’s recommended to get Hep B serologies in all PLHIV, which include:

HBsAb (hepatitis B surface antibody)

HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen)

HBcAb total (hepatitis B core antibody)

We also want to screen for Hep C. Luckily HCV is a curable infection, so we want to get our patient on treatment right away if they do come up positive.

BMP

As you may know, a BMP gives a snapshot of the overall health of our patient, including blood sugar levels and important electrolytes, like sodium and potassium. A BMP also gives us an idea of kidney function. As you'll soon see, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are a key component of ART regimens. It turns out that every NRTI (except one) requires a renal adjustment, so a serum creatinine (SCr) will be needed to determine if our patient is good-to-go from a CrCl standpoint.

And back to blood sugar. Like in any patient, it’s a good idea to take a look at a serum glucose. Not only to rule out diabetes, but one treatment class in particular that we’re about to cover, protease inhibitors (PIs), really screw with blood sugar. So if elevated, we’ll also want a hemoglobin A1c.

CBC w/ diff

Ordering a CBC won’t tell you anything specifically pertaining to HIV, but remember that HIV's M.O. is making people sick with other infections via infecting our CD4+ lymphocytes. The CBC w/ diff helps to evaluate that by breaking down white blood cell (WBC) counts. It also gives a good baseline on where your patient stands in terms of anemia (RBC and hemoglobin) and bleeding risk (platelets).

Liver Panel

Liver function tests (LFTs) include our liver enzymes (e.g., ALT, AST), total bilirubin, etc. A lot ART regimens include agents that are metabolized by the liver and/or can cause liver toxicity. So for some PLHIV, especially those with comorbid hepatitis, we may need to adjust doses of their ART based on their liver function.

Fasting Lipid Panel

A lipid panel is optional, but as we’ll see shortly, there is one treatment class (PIs, again) that we really want this for. Please note that this test must be done in a fasted state. One of the most common causes for crazy numbers on a lipid profile test is the patient eating a Denny's Grand Slam before coming to their appointment.

That "fasted" bit has a habit of showing up on tests as well. I've seen more than one patient case study question that snuck in a patient eating before taking a lipid test.

May consider: HLA Test

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) is a protein on the surface of macrophages and other antigen presenting cells. As pharmacogenomics has entered the scene, HLA tests have played an increasing role in drug therapy. There are thousands of known variations (i.e., polymorphisms) of HLA.

HLA-B*5701 is a very important one to remember because 1) you’re bound to see it on an exam (like the NAPLEX) and 2) it’s one of the few HLA tests that is required before treatment.

If your patient has not been tested for HLA-B*5701 or has been tested and is HLA-B*5701 positive, they cannot receive abacavir (a component of one of our preferred ART regimens) because they have a high chance of developing a major, life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir.

Luckily, there are several non-abacavir-containing regimens. So if going with one of those, you can leave this test off.

Treatment Goals

What is our end game here? We know that there is no cure for HIV. So what are we actually trying to accomplish with ART? To start, remember our chat about viral suppression? Well here it is again at the top of our treatment goals list:

Maximally and durably suppress plasma HIV RNA

Restore and preserve immunologic function

Reduce HIV-associated morbidity and prolong the duration and quality of survival

Prevent HIV transmission

To break it down further, less copies of viral RNA in the blood = less immune cells (i.e., CD4+ cells) affected = more robust immunity = less OIs = better quality of life. Most importantly, lower HIV RNA levels are associated with lower rates of transmission. U=U!

Treatment Considerations

Before we dive into what the recommended ART regimens are and how the individual components work, let’s walk through some fundamentals of HIV treatment initiation.

1. Start Treatment. Immediately.

I’m sure you’re not surprised to hear that ART is recommended for all patients who test positive for HIV, regardless of their viral load or CD4 count.

This next part is a major change from our original Ultimate Guide to HIV article. Now, instead of waiting for an HLA test (and other labs that take time to result), it is recommended to initiate ART immediately (or as soon as possible) after HIV diagnosis.

Why? Wouldn’t it be like, incredibly overwhelming to not only receive an HIV diagnosis, but to also be handed a bottle of pills you’re told you’ll be taking for the rest of your life in the same day?

Uhhhh, yeah. It’s awful.

But there’s a good reason we want to start treatment at entry to care.

Other than the practical consideration that a lot of patients diagnosed with HIV are lost to follow-up due to the stigma associated with their condition, two large randomized controlled trials (ART-START and TEMPRANO) have shown improved outcomes among individuals who received ART immediately compared to those who delayed ART initiation.

Specifically, patients who received ART at diagnosis had increased uptake of ART and linkage to care, decreased time to viral suppression, and improved rates of virologic suppression.

Sold? Thought you would be.

2. Initiate Combination Therapy with a Preferred Regimen

OK so initiate therapy immediately. Got it. What therapy?

I’m glad you asked.

Whatever you do, don’t give monotherapy.

As we mentioned earlier, HIV mutates constantly. The way we can overcome this is by targeting the virus at multiple different stages of the HIV life cycle.

In other words, let’s target multiple phases in the HIV life cycle by—you guessed it—administering combination therapy with drugs that have at least 2 different mechanisms of action.

So, instead of just targeting reverse transcriptase, we should strategize another angle of attack.

And if you remember anything from this article, remember this:

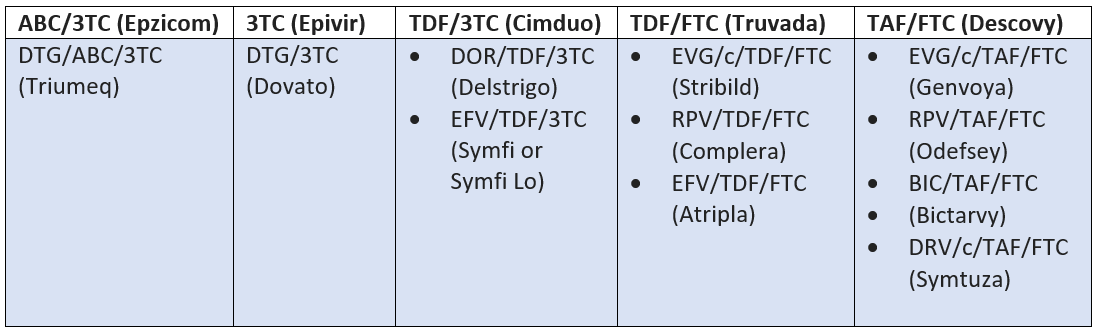

When it comes to preferred ART regimens, most (with some exceptions) are triple therapy composed of 2 NRTIs + “something else”, where the NRTI (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor) is the backbone of the regimen and the “something else” is usually an INSTI (integrase strand transfer inhibitor aka integrase inhibitor).

More on NRTIs and INSTIs in a bit when we dive into each class individually. For now, let’s talk about what the actual preferred regimens are in a patient who is newly diagnosed with HIV.

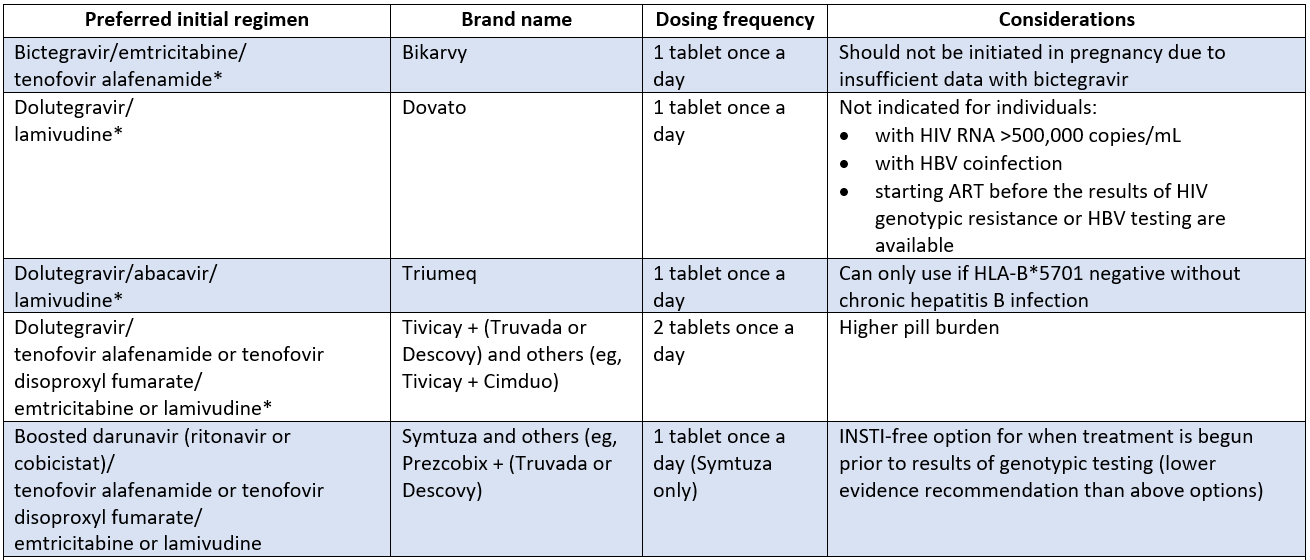

Preferred Initial Regimens

Below you’ll find the 5 preferred initial regimens for MOST PLHIV (we’ll dive into options for treatment-experienced patients later) as of September 2022, which is when this section of the guidelines was last updated. Things may be different in a couple months, weeks, or even days, so you may wanna peruse the current guidelines before burning this table into your mind.

*ONLY recommended for PLHIV who have NOT received the new long-acting INSTI, cabotegravir (CAB-LA), for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We will NOT be delving into PrEP here (that’s another article in itself, so here’s is a great overview in the meantime while we work on that) but we WILL be covering CAB-LA in the INSTI section.

As you can see, a lot of these preferred regimens are one tablet, once a day. Also known as single tablet regimens (STR).

In order to fully appreciate this feat, I’m gonna take a moment here to pause and appreciate how far we’ve come with ART.

Long before STRs were even within reach, some regimens were up to 20 pills a day. TWENTY. And these had to be taken at different intervals throughout the day.

Imagine the impact this pill burden had on your quality of life back then. Not only that, but each time you have to step away to take your medication, it’s a constant reminder to you (and others you’re with) that you have HIV.

Taking less pills doesn’t completely eliminate that stigmatizing feeling, but at least reduces the number of daily reminders.

Anyway, back to STRs. You’ll notice that there’s one little exception to the 2 NRTIs + “something else” pattern.

That would be Dovato, which is a coformulation of just 2 drugs, dolutegravir and lamivudine. Approved in April 2019, Dovato is just another reflection of the speed at which HIV is being revolutionized from a death sentence to a very manageable chronic disease.

Ok so fewer drugs, but just as effective as a 3-drug regimen. Yes, but there’s a catch. There are several limitations that may prevent use of this new combination. One of which is having a high viral load (>500,000 copies/mL), which unfortunately, is a lot of patients at diagnosis.

3. Initiate Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis

Despite the availability of these combination therapies, the CDC estimates that 34% of Americans with HIV who are aware of their HIV infection are not effectively virally suppressed and an additional 13% are completely unaware of their HIV infection.

In other words, nearly 50% of those with HIV are living with an infection that is uncontrolled.

Remember, OIs are rare infections that we really only see when patients are severely immunocompromised.

With HIV specifically, we've been able to correlate OI risk to CD4 count, which if you recall, is a major reason we monitor it at baseline and periodically.

What’s the best way to stop an infection? Prevent it from happening in the first place.

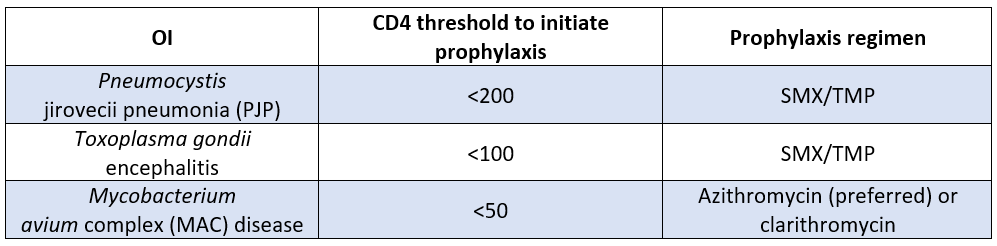

There are 3 main bugs to worry about here when we’re talking about OI prophylaxis in PLHIV. Here’s a breakdown of CD4 counts where you'd need to begin prophylaxis along with the recommended prophylaxis for that bug.

Just remember that we start prophylaxis when the CD4 count dips below 200 cells/mL and you’ll be good. What’s nice is that Bactrim covers both PJP and Toxoplasma. So, when you start a patient on PJP prophylaxis, you're also covering toxo.

There are a number of OIs that we do not routinely recommend prophylaxis for unless certain risk factors are present, like cryptococcal meningitis and TB.

Simplify Your Studying with The HIV Cheat Sheet

It’s hard to even call this a cheat “sheet,” as this sucker weighs in at 16 pages. But you could call these 16 pages “Basically everything you need to know about HIV pharmacotherapy.” It’s got renal/hepatic dosing adjustments, adverse effects and clinical pearls, brand/generic/abbreviation for every drug and combination product, preferred regimens for healthy adults, pediatrics, and pregnancy, opportunistic infection prophylaxis and treatment, adult and pediatric dosing tables, drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, and (seriously) a lot more.

This cheat sheet will save you a ton of time and frustration as you prep for the NAPLEX or any time you come across HIV in your practice.

It’s yours for only $19.

III. Antiretroviral Treatment

Alright, so we talked about the preferred ART regimens for HIV. Let’s get down to the nitty gritty of what makes up these regimens.

Reverse transcriptase inhibitors

Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs)

Protease inhibitors

Entry inhibitors

Fusion inhibitors

Capsid inhibitors

We’ll spend a little more time on the first 3 classes (RT inhibitors, INSTIs, and PIs), as they comprise 99% of what you’ll encounter in practice.

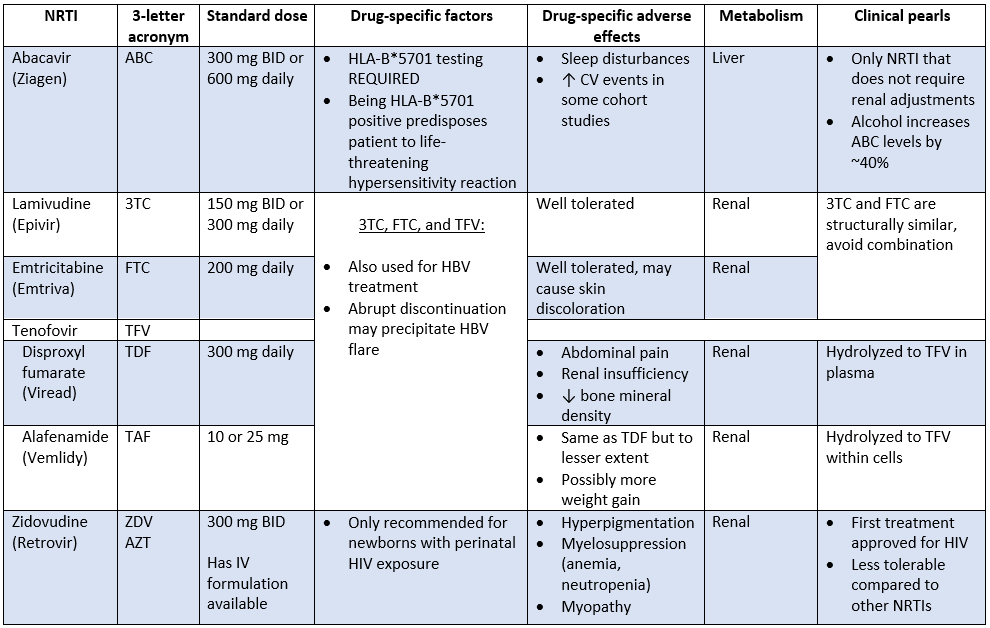

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs)

Remember HIV’s claim to infamy, good ol’ reverse transcriptase? You know, the enzyme that HIV uses to devise its evil scheme of converting RNA to DNA as it goes on its path of destruction?

Yep, that one. Why don’t we block that?

That’s exactly what we did. In fact, zidovudine (the OG NRTI) was our very first stab at irradicating the virus.

Fast forwarding to now, NRTIs (AKA “nukes”) still make up the "backbone" of ART. I actually can’t think of a single regimen that doesn’t have at least 1 nuke.

So, when it comes to nukes, there are 2 flavors: nucleoside and nucelotide RT inhibitors. Though they work exactly the same way, they are technically different. Like vanilla and French vanilla. Same same, but different.

To put it simply, a nucleoside is one of the 4 DNA base pairs (A, T, G, or C) attached to a sugar.

A nucleotide is the same thing but with a phosphate attached to it. When a nucleotide loses its phosphate (through hydrolysis or whatever), it becomes a nucleoside.

Why does this matter?

First, it’s just good to know that all nukes available on the market are nucleoside analogs, except for tenofovir, the only nucleotide analog. You can remember that by the “t” in tenofovir and nucleotide.

Second, NRTIs are nucleoside analogs and their structure plays a major role in their mechanism of action. Nukes are designed to mimic natural nucleoside and nucleotides in structure, but not in function. By the way, you’ll notice that a lot of NRTIs end in -ine (e.g., zidovudine, lamivudine) just like our base pairs (e.g., adenosine).

See where I’m going with this?

NRTI Mechanism of Action

OK, so think of nukes as nucleoside/nucleotide imposters. They “trick” HIV into incorporating them into the growing viral DNA strand. This stops transcription because the NRTI in the strand isn’t the OG base that RT needs to keep transcribing.

No transcription? No viral integration into host genome. No viral replication.

Beautiful.

What’s not so beautiful is that since they mimic the real structures, nukes not only screw with reverse transcriptase, they also screw with the enzyme we depend on for transcription, DNA polymerase. Downstream, this mucks up a lot of stuff, but particularly the mitochondria. The mito-freaking-chondria.

So what happens when you screw with the powerhouse of the cell? It ain’t pretty, that’s for sure.

Class side effects of NRTIs include things like:

Myopathy

Lactic acidosis

Hepatomegaly with steatosis

Lipoatrophy

Peripheral neuropathy

These can happen with any NRTI but are much more likely to occur with older NRTIs. Think didanosine, stavudine, and zidovudine.

With “newer” generation NRTIs (e.g., emtricitabine and lamivudine), things like lactic acidosis and liver issues are, for the most part, pretty rare. In fact, they’re usually very well tolerated and can be blamed for the phasing out of the older nukes in clinical practice recommendations (in the US, at least). This is, with the exception of zidovudine, which you’ll see still has a place in therapy for a very small patient population (literally).

As you’ll see below, there are several other NRTIs on the market and each have their own quirks, special considerations, drug-specific side effects, and clinical pearls.

Looking for the evil twin sisters, didanosine (Videx) and stavudine (Zerit)? They’re are no longer recommended in the treatment guidelines. In fact, they are included on the What Not to Use list. They’re just dirty drugs associated with high incidences of neuropathy, pancreatitis, and fatal hepatic events. Oh, and rash, N/V/D, and headache, although these are the least of your worries.

So, what’s the deal with tenofovir?

We’re glad you asked.

Before we move on to our next class, tenofovir is worthy of a special mention. As you may have noticed, not only can tenofovir be used to treat HBV, but it also has 2 different salt formulations: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF, or Viread) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF, or Vemlidy).

When floating around in the plasma, tenofovir is pretty toxic. Specifically, to our kidneys and our bones. With TDF, most of the active tenofovir ends up right in the plasma, so it’s not uncommon to see some renal insufficiency and/or loss of bone mineral density with TDF.

TAF was designed to be less toxic. The majority of it, upwards of 90%, is hydrolyzed within cells. This results in less nephrotoxicity and less bone loss compared to TDF. And because TAF has better cell penetration, it can be given at a lower dose and maintain the same efficacy.

Think of TDF as that pair of shoes in your closet that you know you have, but just never reach for because you have better ones that don’t hurt your feet as much.

TAF is like your go-to pair of white sneakers. They look good with everything. You can walk miles in them without worrying about blisters.

Why do we care?

Because tenofovir (both as TDF and TAF) is included in ART regimens ALL THE TIME.

Knowing the difference between TDF and TAF is key to selecting the right regimen for the patient. For example, say you have a patient with chronic kidney disease. It would probably be a good idea to steer clear of Truvada as an NRTI duo and go with Descovy instead. And just to clarify, Truvada or Descovy would NOT be a complete ART regimen. Be sure to slap on an INSTI (coming up next), too!

Speaking of NRTI combos, there are quite a few. For your reference, below are the NRTI backbones and their corresponding STRs.

What, you haven’t memorized all the 3-letter abbreviations yet? Don’t fret. All of them are included in their respective class sections.

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs)

Alright, stay with me here. We’re going to take a quick detour from RT inhibitors. That’s because INSTIs have made quite the splash in the ART pool over the last few years. More like a tsunami, actually.

They’ve changed the game so much that they’ve moved all the way to the tippy top of the treatment guidelines and can now be found in virtually every preferred ART regimen.

Of course, there’s an exception because there always is, right? The only INSTI-free initial option currently recommended (albeit a low evidence recommendation) in the guidelines is for cases where treatment is begun prior to results of resistance genotypic resistance testing.

Both INSTIs that are most commonly used have a high barrier to resistance. However, if, at any point, genotypic results reveal that a patient has an INSTI-resistant virus, then we’ll also need to pivot away from INSTIs.

Otherwise, in 99% of cases, you’re going to want to make sure you’re starting a patient on an NRTI duo (or single NRTI in the case of Dovato) plus an INSTI.

INSTI Mechanism of Action

Think of INSTIs as the glue that holds that NRTI backbone together. They reinforce the action of NRTIs by providing a second layer of activity against the virus.

So, it’s like stepping on a rake, which hurts your foot because the prongs are sharp (NRTI), only to be bonked in the head with the handle a split second later (INSTI). If one doesn’t take HIV out, the other will.

But what are integrase inhibitors actually doing to HIV?

They inhibit integrase. Duh!

Just kidding. Let’s have a chat about integrase first.

Integrase, like RT, is just another enzyme HIV uses to do its dirty work.

It takes the DNA that was just made by RT and inserts it into the host cell genome. Integrase literally says “cut and paste”. The end result is viral DNA sitting right in the middle of your own DNA strands. Just making itself at home.

To do all this, integrase needs magnesium (Mg2+). It’s a critical co-factor. No Mg2+, no integration.

INSTIs go to the active site of integrase and bind up all the Mg2+, leaving integrase magnesium-less and unable to do its “cut and paste” thing.

And remembering that HIV is a virus, it needs your cell to complete its own replication cycle. If it can't incorporate its genome into yours with integrase, it cannot replicate. Simple as that.

The only problem is that INSTIs don’t selectively bind to the Mg2+ that integrase wants to use, right? They also trap the rest of the Mg2+ (and other divalent cations) floating around.

You may remember that other drugs, like tetracyclines, do this too. So what you’re about to hear might seem a little like déjà vu…

All INSTIs (with one new-ish exception) should be given at least 2 hours before or 6 hours after products containing divalent cations (e.g., magnesium, aluminum), such as antacids, laxatives, dairy products, and multivitamins. Not spacing these out could result in decreased levels of the INSTI, which could compromise efficacy.

INSTI Adverse Effects

Other than the divalent cation thing, INSTIs are pretty well tolerated…especially compared to other ARV classes, like—dare we spoil it—protease inhibitors.

Below are some class effects that may be seen with any INSTI:

Non-specific side effects like weight gain, nausea, diarrhea, headaches, insomnia, yadda yadda

Modest increases in creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and SCr

Mood changes (depression and suicidality are rare and occur primarily in patients with preexisting psychiatric conditions)

Potential for drug-drug interactions, as most INSTIs are minor CYP3A4, P-gp, and UG1A1 substrates. All INSTIs are contraindicated with dofetilide

Like NRTIs, not all INSTIs are created equal. Below are some drug-specific considerations.

Note we won’t be including combination regimens here because those were either covered in the Preferred Regimens or NRTI sections. Which makes sense right? Because INSTIs are first-line and are always used in combination with an NRTI!

*only approved as a switch option, which means the patient must already be virologically suppressed

That’s a lot of information.

If it helps, you likely won’t see raltegravir or elvitegravir, the first 2 INSTIs to market, in practice.

Dolutegravir

Both raltegravir and elvitegravir were by far more tolerable than other products when they first came out. But when dolutegravir hit the market 2013, everything changed. That’s when things really started to shift in the direction of team INSTI with dolutegravir holding the team on its back.

So why the shift?

To start, dolutegravir doesn't need to be boosted so it has far less drug-drug interactions compared to elvitegravir. And unlike raltegravir, it’s dosed once daily. It also doesn't have the untoward CPK/liver effects that come with raltegravir.

What really brought dolutegravir to the forefront of INSTI regimens is the fact that it binds tighter and more selectively to the integrase active site than elvitegravir or raltegravir. This gives it a higher barrier to resistance. Not only that, it has also shown efficacy against HIV strains resistant to the other INSTIs.

Another great thing about dolutegravir is that it’s available as a single agent (Tivicay), so it can be mixed and matched with other components to complete an ART regimen. For example, it can be given with TDF/FTC (Truvada) or TAF/FTC (Descovy), both of which are preferred regimens.

You can also find dolutegravir in the once daily combination pill, Triumeq (contains abacavir, so don’t forget that HLA test!) and the fancy, once-daily 2-drug regimen we introduced in the section above, Dovato.

And lastly, it’s also available in combination with rilpivirine as Juluca, a once daily option, but only as a switch (not initial) option in PLHIV who are virologically suppressed.

Bictegravir

After dolutegravir came bictegravir, which is very similar in the sense that bictegravir also has a high barrier to resistance and is pretty well tolerated.

The main difference is that you won’t find bictegravir alone on the shelves like you can with dolutegravir. It’s like that one friend you have who is always dating someone. They’re never just content on their own.

Biktarvy, the combination product, is the only way you’re gonna get your hands on bictegravir. It’s a package deal.

Bictegravir does have good taste, though, unlike some folks. Bictarvy is a great option because it’s formulated with TAF, so you’re not stuck with TDF.

And just to bring this full circle in case you forgot, Biktarvy and most other INSTI-based preferred regimens mentioned earlier are one pill given once a day.

20 pills a day to now…just one? Seriously incredible.

Cabotegravir

Speaking of the evolution of HIV treatment, I would be remiss we didn’t at least spend some time on the newest INSTI that hit the market in 2021.

Cabotegravir is a game changer for a couple reasons.

First, it’s formulated in a novel delivery system. A long-acting injectable suspension (CAB-LA). It’s given IM and…get this… only needs to be administered every 1 or 2 months. No more pills in your medicine cabinet that serve as constant reminders that you have HIV.

Second, CAB-LA is approved for HIV treatment (Cabenuva, cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine, which is an older drug in the NNRTI class that we’ll get to shortly) AND, though we won’t be covering this use, prevention (Apretude, which is cabotegravir alone).

Before we toss the pills completely, there is a catch. A pretty big one. Cabenuva is only approved to replace a stable oral regimen in PLHIV with sustained virological suppression (defined as HIV RNA <50 copies/mL for Cabenuva) for at least 3-6 months. In other words, it cannot be given to a newly diagnosed or treatment naiive patient. It’s a switch option, like Juluca (DTG/RPV) we just discussed.

So, let’s say a patient is controlled on their current regimen. They’ve had an undetectable viral load for over a year. Second, this patient is also a potential candidate for switching to CAB-LA.

But, not every patient is a good candidate for switching to CAB-LA.

Here’s what I mean by that. Let’s say this particular patient has a history of nonadherence to their Biktarvy. They admit to missing a couple doses a week. Believe it or not, you can actually go on like this for a while and stay undetectable. That’s how well these INSTI combos work. After a period of time, though, resistance can develop, and the virus can begin replicating again.

So, knowing your patient has an issue with adherence, you may reconsider switching them to a treatment that requires them to physically come in to get their injection. If they don’t come in, they’re at risk of developing resistance. Just like it would if they stopped taking their oral medication.

Alright, so say in a magical world your patient never misses a dose of their Biktarvy. You trust they won’t just ghost you after you switch them to CAB-LA.

But… they’re terrified of needles.

You’re going to have to break the news to them that this treatment involves not just one, but 2 injections each time. One of cabotegravir. One of rilpivirine.

And not like a standard 1 mL injection we typically see with vaccines. Oh no…the first round of CAB-LA is 3 mL injections. Two of ‘em.

After that, the patient can opt for either 1-month or 2-month treatment option.

With the 2-month option, you’re getting those same 3 mL injections every 2 months vs 2 mL injections with the 1-month option.

And by the way, CAB-LA is administered via gluteal injection. AKA the booty. Getting 2 or 3 mLs anywhere would be painful. But people really have an issue with the placement of this shot, especially if you ever, you know, sit down in a chair or in a car.

Fun fact, I actually did an internship with the company who makes Cabenuva. One thing burned (literally) in my mind was the safety data from these CAB-LA studies. Over and over again I recall reading about how much these injections hurt, especially the 3 mL ones. To the point where a lot of subjects were so sore at the injection site that they literally had difficulty walking for like a week after their shots.

And just like with other INSTIs, there is also the possibility of allergic reactions, liver issues, and mood changes. But, since we’re bypassing first pass metabolism with Cabenuva, we don’t need to worry about spacing out divalent cations.

So, all this considered, if you trust that your virologically suppressed patient will show up for treatment every month (or every 2, depending on how high their pain tolerance is), then the last thing we’ll need to do is make sure the patient will actually tolerate the combination. You know, before, injecting them with something long-acting. We do this by having the patient take an oral lead-in with a cabotegravir pill (Vocabria) and a rilpivirine pill once a day for a month.

If they tolerate that (and the massive injections), then we can kiss that bottle of pills goodbye!

Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs)

NNRTIs (pronounced like NRTIs, but with a stutter), are the next class of HIV drugs we'll be covering. You can also call them “non-nukes”.

NNRTI Mechanism of Action

Non-nukes are, you guessed it, not nucleoside analogs.

Unlike nukes, which bind to the active site of reverse transcriptase to shut down replication, non-nukes bind to a different spot (an allosteric site) on reverse transcriptase. When they bind, the shape of the enzyme is altered enough that it can no longer bind to real nucleosides.

So same target as nukes, different mechanism of shutting down reverse transcriptase.

So once again, HIV genome replication shuts down and everyone is happy. Except for HIV, of course.

NNRTI Adverse Effects

The cool thing about NNRTIs is that because they don't look like nucleosides, they don't have the mitochondrial toxicities of the NRTIs.

No need to worry about lactic acidosis here.

The downside is that NNRTIs have their own problems. Problems that make giving them a little tricky.

NNRTIs as a class are associated with:

Hypersensitivity (most commonly rash, but can be as severe as SJS/TEN)

Liver toxicity (elevated LFTs, hepatitis, or as severe as liver failure), which is especially a concern with HBV/HCV co-infection

Drug-drug interactions…lots of drug-drug interactions

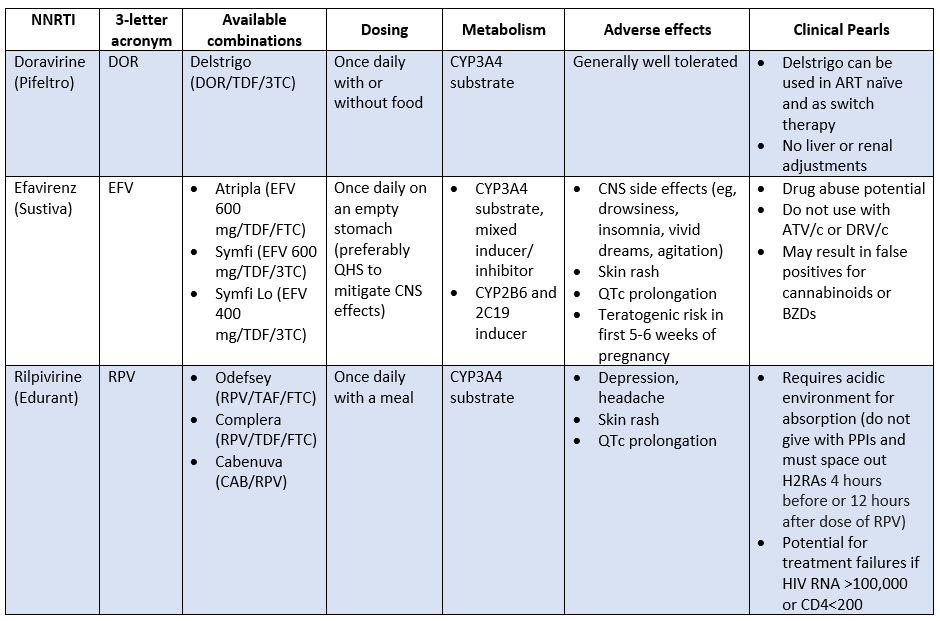

These are the main 3 you’ll see in clinical practice. All of these triple therapies come in single tablet regimens, which is super convenient.

It's worth mentioning that nevirapine and etravirine are still on the market but aren’t NNRTIs currently recommended as part of ART. These guys are notoriously bad when it comes to rash, liver toxicity, and DDIs. So, you likely won’t see these in clinical practice.

And honestly, other than the new kid on the block, Cabenuva (with rilpivirine), NNRTIs as a class have been….kinda phased out of the treatment guidelines over the years.

And to think not long ago, one of our preferred ART regimens was 2 NRTIs + an NNRTI. Now, as you may recall, it’s almost always 2 NRTIs + an integrase inhibitor. Just another example of how quickly HIV treatment is evolving!

Why the shift?

Well, doing a rotation in an HIV clinic, I can say that the DDIs and absorption issues (requiring changes in diet) are major pain points with using NNRTIs.

And Brandon can vouch for those CNS effects. He once spoke with a patient who stopped taking his Atripla because he had a dream that he rose out of his own body and killed himself. More like A-trippy-la.

If that’s not traumatizing enough, NNRTIs have another strike against them.

Aaaaand that’s cross-resistance. Unlike some other classes of ARVs, NNRTIs do not do well in the face of resistant strains of HIV. In other words, if a patient becomes resistant to efavirenz, for example, that patient likely just lost the entire NNRTI class as a treatment option. No bueno.

This is a lot to memorize. Make it easier on yourself with an HIV Cheat Sheet.

It's yours for only $19

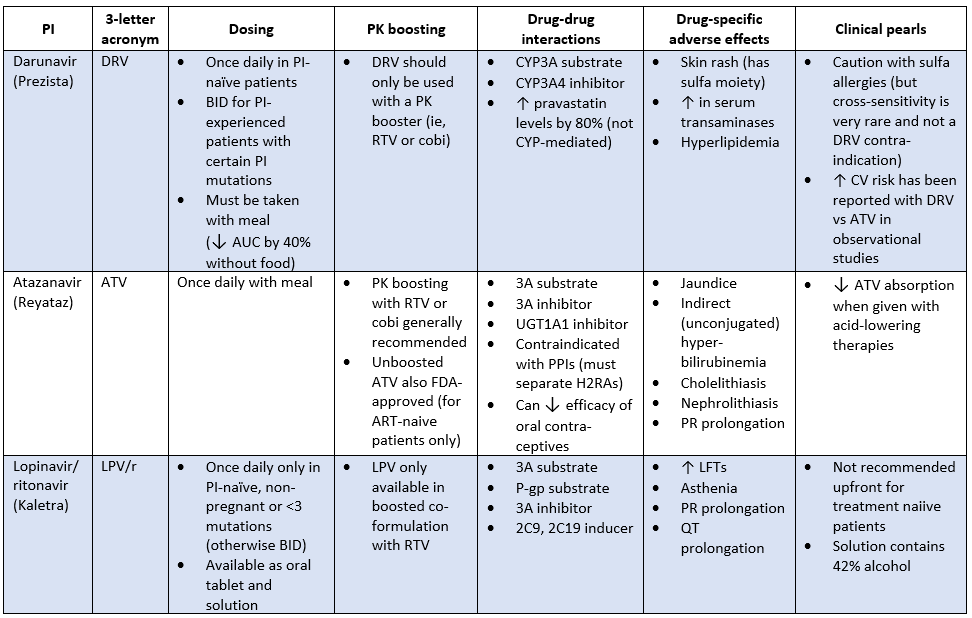

Protease Inhibitors (PIs)

Not going to sugar coat it. PIs are dirty drugs.

Like NNRTIs, PIs have for the most part been given the treatment guideline boot. Quite honestly because when combined with nukes, INSTIs just work better and are much more tolerable. No brainer, right?

You may still see a PI pop up on a med list every now and then, especially with underinsured PLHIV (PIs, especially the older ones, are dirt cheap), and those who either need to start treatment prior to resistance testing results or have already developed resistance to INSTIs.

In fact, unlike our NNRTIs, they have a high barrier to resistance. Yes, there are certain mutations that will knock out several PIs. But in general, if resistance develops to one PI, you can still use another.

So we’re still going to cover what you need to know for those 1 or 2 questions on the NAPLEX, but you won’t see all super-duper granular detail like we did back when this was originally written. You’re welcome.

PI Mechanism of Action

Ok, so what’s protease, and why do we want to inhibit it?

Well, as you probably guessed by the “ase” at the end of protease, it’s yet another enzyme HIV relies on to replicate.

That’s because when HIV initially translates its viral genome from RNA to DNA back to RNA, the proteins it spits out are… not quite mature.

In fact, they’re completely non-functional proteins.

You know, kinda like the first draft of that paper you wrote in your college English class. Filled with all kinda gramatical errors and run on sentences that just keep going and going and going and comas in, (ahem) wrong places.

The initial viral proteins look kind of like that ^^ dumpster fire.

So HIV protease comes in and makes it look more like a distinguished scholar, like Spongebob, wrote it.

In a sense, HIV protease is the copy editor of the viral translation process. When its job is done, what's left is a protein that's ready to go for publication.

And if we were to leave the copy editor out of it?

We're left with that rough draft, and aint nobody reading that. Return to sender.

In the case of HIV, when we inhibit protease, we essentially leave HIV with a steaming pile of protein poo. They literally have no use. And if the virus can’t make proteins, it can’t replicate. What does that leave? An immature, non-infectious virus.

Sounds pretty intuitive right?

PI Adverse Effects

Let’s talk about why these drugs get such a bad rap. Side effects associated with all PIs are:

Hyperlipidemia

Fat maldistribution (peripheral fat wasting/central fat accumulation)

Insulin resistance/hyperglycemia

GI complaints

Bleeding episodes in hemophiliacs

Hypercholesterolemia

Hypertriglyceridemia, can have ↑ LDL and ↓ HDL

Fortunately, there are 2 PIs that at least have a much lower risk of metabolic issues compared to the others. Darunavir and atazanavir are actually the only PIs recommended in the clinical guidelines, specifically for rapid ART initiation, or in the setting of acute HIV infection before resistance test results are available.

And when I say metabolic issues, PIs can REALLY screw with a person's metabolism. They can induce metabolic syndrome. They increase blood sugar. They increase serum lipids.

They can cause lipodystrophy. That's right. PIs can literally move fat from one part of your body to another. This is where you'll see buffalo humps and moon face.

Sprinkle in some hepatitis (PIs can increase LFTs) and an increased risk of bleeding in hemophiliacs and you’ve got a recipe for fun.

If you're thinking, "I'll just give the patient a statin to counteract the lipid increase," think again. Or at least choose carefully. Simvastatin and lovastatin are contraindicated with every PI. There are specific recommendations for the rest of the statins, but the general rule is "start low, go slow."

PI Drug-drug Interactions

Just going to drop this amazing DDI checker here. You’re gonna need it if you’re using a PI.

If the side effect profile of PIs didn’t scare you away, the drug-drug interactions might.

To start, every PI is a CYP 3A substrate. PIs also inhibit multiple CYP pathways, UGT1A1, and P-gp.

CYP interactions are particularly irksome if the patient happens to need anticoagulation. Every single one of the NOACs is contraindicated with PIs. Warfarin can be monitored, but you've gotta keep it on a tight leash.

You'll also need to watch out for anticonvulsants. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam are usually OK, but you're just asking for a headache if the patient is on phenytoin, carbamazepine, or valproic acid.

You're basically having a contest to see which drug "wins" on having the biggest impact on the CYP pathway.

Here’s where the DDIs become a major problem with PIs.

Alone, PIs don’t always reach concentrations that can keep up with HIV. To give PIs a little extra “umph”, we take advantage of the fact that PIs go through the CYP pathway (mostly 3A4). PIs are almost always “boosted” (or pharmacokinetically enhanced if you want to be fancy), which just means they are administered with a drug that inhibits their metabolism and increases the levels of the PI.

PI Boosters

There are 2 different boosters we can use with PIs. Let’s talk about them really quick:

Ritonavir. This booster is actually is a PI itself, so it does have some activity against HIV, but it’s never given as the sole PI. It’s pretty much just used for its ability to boost levels of other PIs. Being that it’s a PI, it can have some additive toxicity, like those icky metabolic effects. Another downside is that ritonavir also induces enzymes, which may decrease efficacy of concomitant drugs that are CYP substrates.

Cobicistat. AKA cobi. Unlike ritonavir, cobi has no antiviral activity at all. Its only purpose is to boost PIs. Also unlike ritonavir, cobi isn’t an enzyme inducer, so it’s associated with fewer DDIs. And fun fact. Like dolutegravir, cobi can cause modest increases in SCr, but it’s kinda fake news. They pretty much just prevent the elimination of creatinine, which gives the appearance of worsening renal function, but they’re not actually harming the kidneys.

Ok so we talked about boosters, which really ramp up the DDI potential.

Now for a drug-specific PI dump:

Notice we didn’t include every PI on the market. It’s for your own good because there’s no point in filling your brain with something that you’re highly unlikely to encounter. At least we hope you don’t, mainly for the sake of the patient. Looking at you saquinavir (Little Miss PR/QT prolongation…which is most PIs but saquinavir is especially bad) and tipranavir (Little Miss intracranial hemorrhage), and others.

Other ARV Classes

Well, we're coming full circle here. If we were HIV, we’d be almost at the point of budding.

These last few drugs have different mechanisms of action than the ones we’ve already discussed.

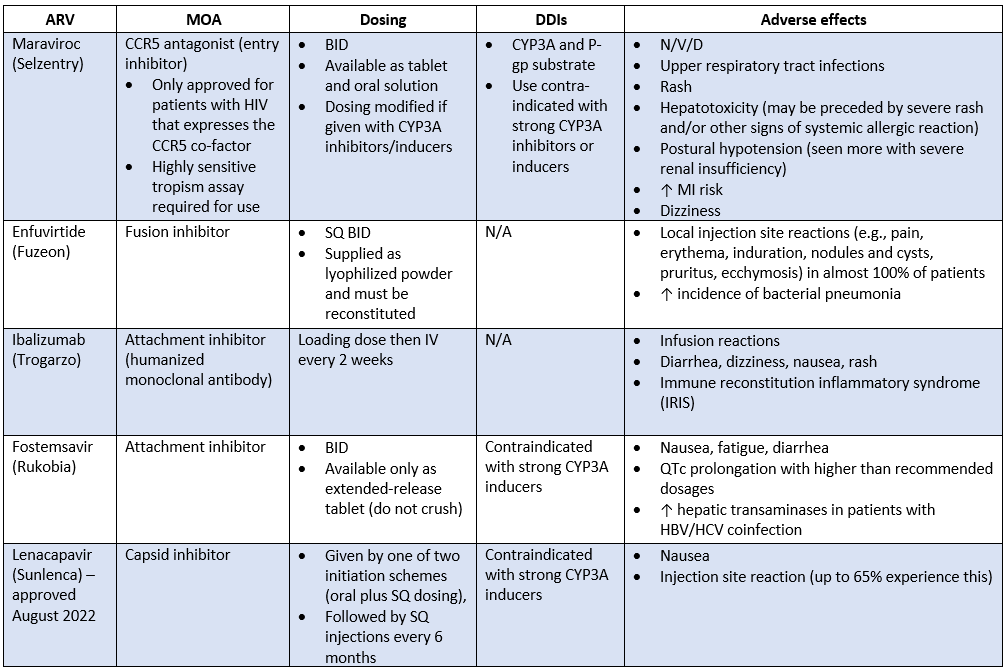

In this last section, we’ll cover:

Entry inhibitors

Fusion inhibitors

Capsid inhibitors (new!)

These 3 classes are typically reserved for PLHIV who have exhausted all lines of therapy we’ve discussed prior. Also referred to as the heavily-treatment experienced (HTE) patient.

These patients either had poor adherence and developed a resistant infection OR acquired a resistant strain of HIV when they were first infected.

We talked about how you’ll rarely see a PI used anymore. These drugs below are even more rare. Which is a good thing, because that means our first-line treatments are doing their job!

IV. The TL;DR of HIV

Ok we covered a lot. Let’s recap.

HIV is a retrovirus that defies the central dogma of DNA > RNA > protein by using reverse transcriptase to convert our RNA to DNA. This viral DNA is integrated via integrase into the genome of host immune cells (mainly CD4+ cells). From there, protease kicks off the process of manufacturing viral proteins, which allow HIV to replicate by infecting other immune cells.

As the virus replicates and the immune system declines, HIV can start causing OIs, which will eventually result in death if not treated.

When it comes to treating a patient with HIV, you’re going to start with getting some labs. Viral load, CD4 count, resistance testing, HBV serologies, and HCV screening are key. After that, start treatment immediately. In most cases, your go-to will be 2 NRTIs (“nukes”) + an INSTI +/- OI prophylaxis if needed. The patient will need to return in 4-8 weeks for repeat labs, then again in another 3 months.

Each treatment class has their own trademark considerations. Like with NRTIs, many of them are also used to treat HBV and can cause serious flares if abruptly discontinued in a patient with HBV. With INSTIs, although well tolerated for the most part, don’t forget to space out divalent cation-containing products. And with PIs, you’ve gotta watch out for those DDIs and nasty metabolic side effects.

There’s just no way we could cover every detail there is to know about this monster of a disease state in one article.

Not only that, this information changes. All the time. So be sure to reference these key resources for the most up to date information:

And if you made it to the end of this article, congratulations. You’ve not only tolerated some ridiculous memes, but you’ve also maybe (just maybe) learned a little bit about HIV in the process.

Do You Want an HIV Cheat Sheet?

It’s hard to even call this a cheat “sheet,” as this sucker weighs in at 16 pages. But you could call these 16 pages “Basically everything you need to know about HIV pharmacotherapy.” It’s got renal/hepatic dosing adjustments, adverse effects and clinical pearls, brand/generic/abbreviation for every drug and combination product, preferred regimens for healthy adults, pediatrics, and pregnancy, opportunistic infection prophylaxis and treatment, adult and pediatric dosing tables, drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, and (seriously) a lot more.

This cheat sheet will save you a ton of time and frustration as you prep for the NAPLEX or any time you come across HIV in your practice.

It’s yours for only $19.