The Total Rundown on Total Parenteral Nutrition

Steph’s Note: So it’s your first day of your ICU rotation, you’re shadowing on rounds, and your preceptor starts discussing intravenous nutrition with the team. And you’re like whaaaaaat… They didn’t teach us THAT in pharmacy school!!

First, don’t panic. Second, you’re not alone - many pharmacists never touch nutrition at all, so it’s not exactly common knowledge in the field. Third, you CAN learn it - just like you learned everything else in school.

And here to help with this is Jordan Kelley, PharmD. I’ll let her introduce herself and then she’s going to FEED your brain! (See what I did there? FEED for a nutrition post??? C’mon, you know you like punny.) Anyways, here she is!

Dr. Jordan L. Kelley, originally from a small town in Mississippi, received her Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy. Dr. Kelley completed a PGY1 at University of Kentucky Healthcare, where she is currently completing a PGY2 in Internal Medicine. Her practice areas of interest include Internal Medicine, Hepatology, and Transitions of Care. Ultimately, she plans to pursue a clinical pharmacy position and adjunct faculty responsibilities to continue teaching and mentoring young pharmacists. In her spare time, she enjoys traveling, overindulging at new restaurants, and reading books that make you look at the world differently.

Note: If you’d like a downloadable (and printer-friendly) version of this article, you can get one here.

And if you’d like a TPN Cheat Sheet to help you calculate exactly what to give a patient (including macros, electrolytes, and trace elements), then be sure to check out our Critical Care Cheat Sheet

Total parenteral nutrition (PN), the dreaded words for most residents and busy pharmacists when a patient is not maintaining an appropriate amount of nutrition. Just EAT, we often think. FEED THE GUT and get better! But we know that is easier said than done.

Physicians and nurses comment that the patient is not tolerating the tube feeds/diet. What does “not tolerating” mean, and why does that mean jumping to PN? In my experience, “not tolerating” means emesis, diarrhea representing insufficient absorption, gastroparesis, abdominal distention and belly aches, elevated residual volumes, to name a few of the reasons in the book.

However, as tempting as it might seem to jump the gun and go straight to PN, this modality is more than just calculating how many Big Macs you can liquefy and safely inject into the human vein.

It’s complicated. And not without its own risks. Just remember natural physiology of the gut requires it to be stimulated with food, and PN is the equivalent of providing Miracle Grow to any bacteria in the garden. Risks and benefits of PN have to be weighed, and although this post isn’t going to cover the evidence behind enteral nutrition being oh-so-much-better than PN, it’s worth checking out if you’re not familiar.

Also, every patient is different, every problem is different, and clinical judgment is necessary. I’ll try to point out some of these judgment calls as we work through PN.

The best way to approach PN is in steps.

How to Evaluate Candidates for Parenteral Nutrition

1. Which patients need Parenteral Nutrition?

Reasons to administer PN vs reasons not to administer PN often can lead to a gray area when deciding the appropriate route for a patient. I think the best quote to help explain this is:

“Holding enteral nutrition does not rest or inhibit bowel function, and this approach is akin to inducing asystole to rest the heart.”

Starvation decreases blood flow to the gut, which can lead to changes in the GI tract that could increase inflammation and translocation of bacteria. It is known that the best way to improve gut function is to use the gut when it is possible.

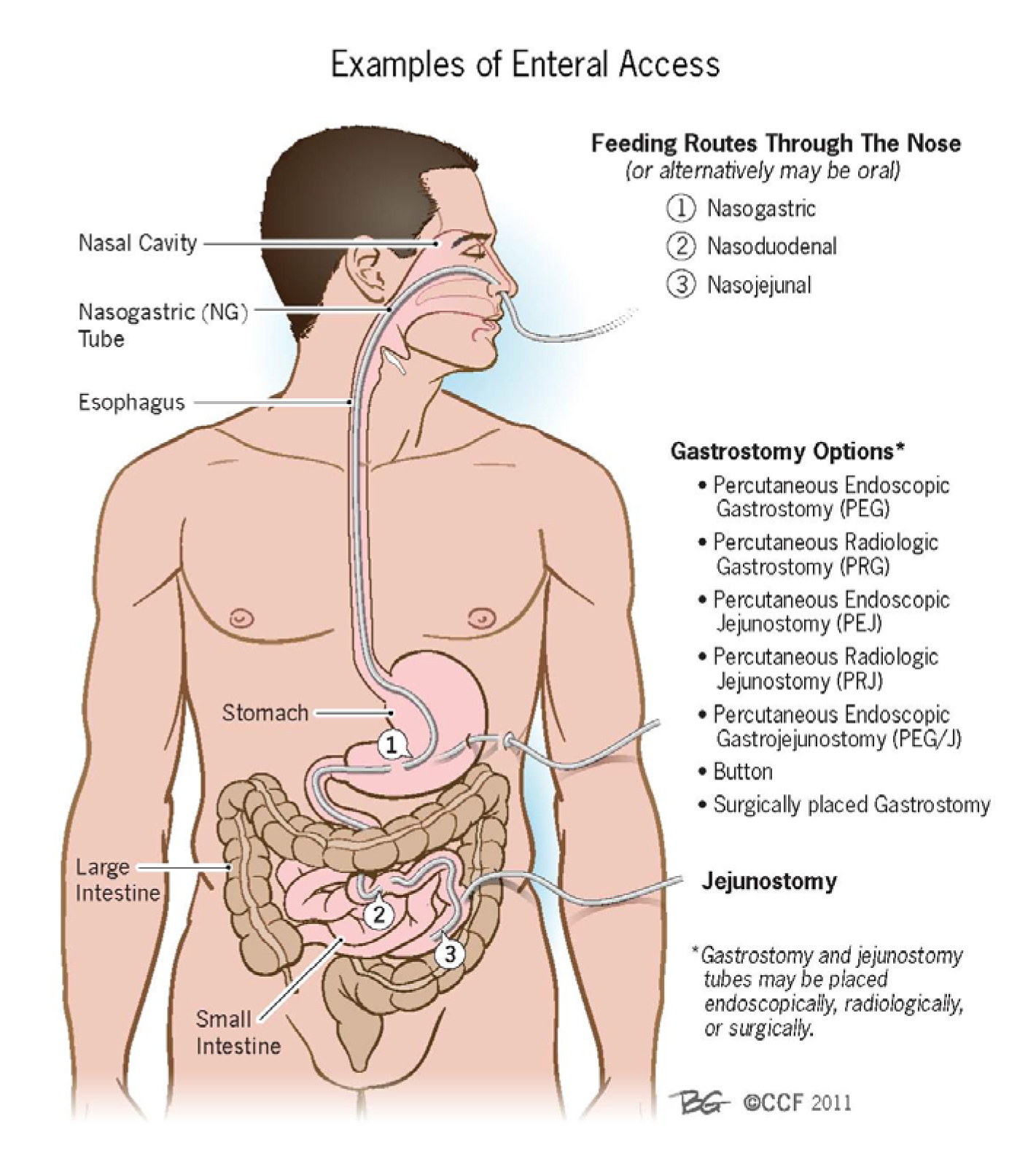

A quick primer on enteral access routes. (Image)

That being said, as much as it makes us cringe, PN is sometimes necessary. Patients may not be absorbing tube feeds or have anatomical/physiological disease states such as short gut syndrome that necessitate supplemented IV nutrition. However, not tolerating tube feeds is not a reason to initiate “Operation IV Liquid Big Mac”. Patients may just need a few more days to adjust to the tube feeds and regain absorption and blood flow to their GI tract.

On that note, please stop measuring gastric residual volumes (GRV) with enteral feeds. GRV does not correlate with incidences of pneumonia, regurgitation, or aspiration. It does not mean the patient is failing tube feeds. The 2016 American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) and Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) guidelines explicitly state that GRV <500 mL should not warrant holding enteral nutrition without other signs of intolerance. So stop checking it!!

2. When should you NOT give Parenteral Nutrition?

Reasons not to give PN are longer than the waiting list for electrolytes to be off of shortage, but we can at least talk about some important ones.

The first reason would be duration. How long do you anticipate the patient will need PN? If a patient is only going to be without enteral nutrition for a couple of days, then they do not need PN.

Basically, don’t start PN in the first week of treatment even if you can’t get enteral access. It’s just too risky if the patient is not malnourished. When YOU don’t feel good, YOU don’t eat. And you also don’t die from not eating for a few days – so give your patients a chance to heal normally as well.

Another important scenario is the infected or septic patient. The last thing you want to do to an infected patient is give the organisms Miracle Grow, which is exactly what you would do with all of the sugar, amino acids, and fat in PN.

Finally, and I cannot reiterate it enough, PN is never an emergency. Giving PN is not going to miraculously heal or save your patient’s life in the next 24 hours. It may facilitate getting out of the ICU, it may decrease recovery time, but it will not be the intervention that changes the ultimate outcome. Never forget to assess the patient’s underlying clinical picture. We may like to joke that “Food is LIFE,” but that is not realistically the case.

3. What do you need to give Parenteral Nutrition?

So you have decided to give PN. Do you have the right IV access? Do you have a line dedicated to PN? How long do you plan on giving it?

These are all questions to ask the physicians when they are assessing the need for PN. Often, alternative plans are arranged when the risks and red tape associated administering and monitoring PN are fully discussed.

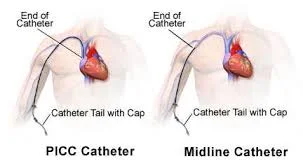

A patient receiving PN should have a designated central line. IV nutritional support is way too hyperosmotic to be tolerated in a small peripheral line, and not even a mid line will work! Go big or go home.

In summary, PN is a possibility…but not a really good option. Providing adequate amino acids and calories is limited and puts the patient at a greater risk for adverse events. Peripheral lines are limited by the osmolality and volume that you can safely give to the patient in a 24 hour period and you will never get them enough nutrition to matter. If the physician says they want to start the PN now and they will get a central line later, remember this:

PARENTERAL NUTRITION IS NEVER AN EMERGENCY!

Get the central line and then start PN after the central line is placed and verified.

PICCs (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters) are common central access devices. Note that the tip of the catheter is all the way in the superior vena cava (aka a large, high flow vessel).

Contrast this with a midline, which ends in a peripheral location (aka a smaller vessel that can not handle total PN). However, peripheral parenteral nutrition (or PPN) may be an option through a midline given its less robust osmolality compared to total PN. (Image)

How to Calculate Parenteral Nutrition Requirements

1. Estimate the Patient’s Fluid Needs

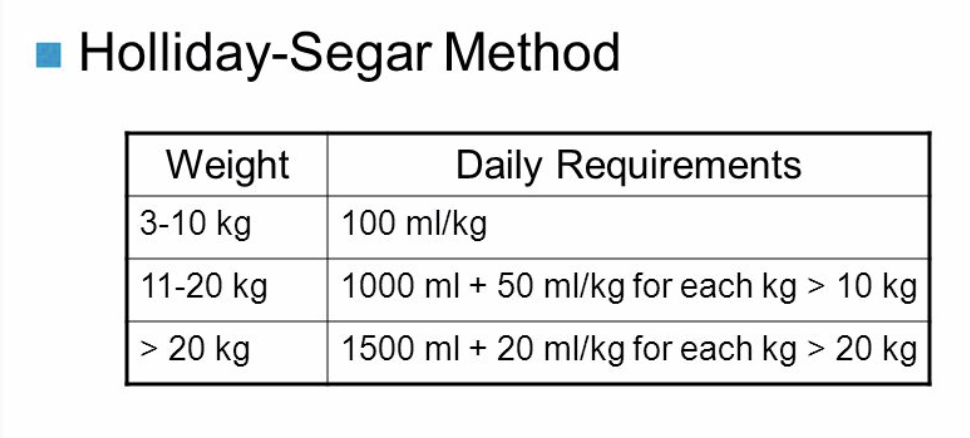

Use the Holliday-Segar Method to determine fluid requirements:

The Holliday-Segar Method for estimating fluid requirements.

For example, a 50 kg patient would require 2100 mL/day (1500 + 20*30). Let’s make it easy and say patient requires ~2 L/day.

How much fluid the patient needs may also depend on sodium status and comorbidities. Fluid status is difficult to assess – but this is generally a decent first start to determine maintenance fluids. Most adult patients will tolerate a 1.5-2.5 L/day of PN.

2. Estimate the Patient’s Metabolic Needs

Now you need to calculate the PN – which takes math, science, and a smidge bit of magic (read: clinical judgment). Estimating nutritional needs can be accomplished using a variety of methods. None of them is wrong. Just use what you feel most comfortable with.

One common option is the Harris Benedict Equation, which predicts resting caloric requirements:

BMR = basal metabolic rate in kcal = Calories (with a big C)

Another option is to do a Metabolic Cart Study (Indirect Calorimetry/Oxygen Consumption), which is the most accurate measure of determining caloric requirements.

Finally, some institutions utilize a weight-based calorie needs assessment, which accounts for the patient’s metabolic state as compared to normal:

Normometabolic patients usually require 25-30 kcal/kg/day. For hypometabolic patients, consider decreasing your weight-based caloric need estimate to 20-25 kcal/kg. For hypermetabolic patients, increase to 30-35 kcal/kg.

However, the magic comes in when a patient is obese or malnourished. Permissive underfeeding in critically ill obese patients is defined in the 2016 ASPEN guidelines. Implement a high protein, hypocaloric feeding to preserve the lean body mass and minimize overfeeding. Patients with a BMI of 30-50 should receive 11-14 kcal/kg/day of Actual Body Weight, and people with BMI >50 should receive 22-25 kcal/kg/day of Ideal Body Weight.

In this case, comparing weight-based dosing to the other equations would help to find common ground between the patient’s energy requirements and calorie restriction needs. The more protein you can use to make up those calories, the better.

An Example of Calculating Metabolic Needs

Patient 1: 50 year old female (50 kg, 167 cm) with ischemic bowel and history of physiologic short gut syndrome admitted for malnutrition. Patient has multiple decubitus ulcers/sacral wounds.

Option #1: Harris Benedict Equation BMR: 655 + (9.6 x 50kg) + (1.8 x 167cm) – (4.7 x 50y/o) = 1200 kcal/day

Option #2: Weight-based given wound healing = hypermetabolic => Use 30-35 kcal/kg = 1500-1700 kcal/day

Option #3: Metabolic Cart Study = 1450 kcal/day

Looking at these 3 options, Harris Benedict underestimated metabolic needs in this patient, the weight-based method overestimated needs, and the Metabolic Cart Study is the most accurate.

So we settle on ~1500 kcal/day.

3. Estimate the Patient’s Macronutrient Needs

Nutrition is broken down into the three main macronutrients: protein, fats, and carbohydrates.

PROTEIN (provides 4 kcal/gram) – “Do you even lift, Bro?”

There are 20 amino acids necessary for…basically everything. These can be broken down into essential amino acids and then further into branch chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, valine, aka The Girls - Lucy, IsoLucy, and Val - as my mentor likes to call them) and aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine).

Proteins are hydrolyzed to smaller fragments and larger fragments require digestion. On the other hand, di- and tri- peptides are absorbed directly. The type of protein becomes important when you have a patient with absorption or digestion issues. While this is more of an issue in enteral nutrition, it is important to recognize how the type of protein could be a barrier to successful enteral nutrition. It is also important to remember that protein is needed for wound healing.

Give as much protein as you can -> give them all the “GAINZ.”

The following are some ideas of how to estimate daily protein requirements:

Maintenance, Unstressed: 0.8 - 1 g/kg

Mild stress: 1 - 1.2 g/kg

Infection, Major surgery, Cancer, Critically ill: 1.3 - 1.6 g/kg

Multiple trauma or CHI: 1.4 - 1.6 g/kg

Large wounds, Protein-losing enteropathy: 1.5 - 2 g/kg

>20% Total Body Surface Area burns: 2 - 3 g/kg

Common Mistake: Do NOT use albumin as a marker of malnutrition in the acutely ill patient. Albumin and pre-albumin are negative acute phase reactants due to elevated C-reactive protein synthesis by the liver.

FATS (provide 9 kcal/gram; or easier to remember, 20% IV Fat Emulsion provides 2 kcal/ml) – IV lipids are easy! They come in a bag, so just give the (affectionately dubbed) Fat Bubbles!

Fats are important to maintain integrity of cellular membranes and provide 30-40% of calories needed. Intravenous fat emulsions are long chain triglycerides derived from safflower or soybean oil with purified egg yolk phospholipids. Which means if a patient has an egg allergy, no Fat Bubbles for them.

Remember: arachidonic acid -> cyclooxygenase (COX)/ Lipoxygenase —> INFLAMMATION! (Image)

Regular oral fats contain Omega 3 & 6, but the medium chain fatty acids (MCFA) are easiest to absorb because they don’t need lipase. Regular IV lipids try to mimic these fats, but many of the fatty acids from safflower and soybean convert to arachidonic acid, which leads to increased inflammatory enzymes.

Smoflipids is a newer product that contains 30% Omega 6, 15% Omega 3 (the real good stuff), and MCFA that do not convert to arachidonic acid. So the thought is that Smoflipids may be better for patients with inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease.

Clinical Pearls about Fats:

Compatible with the other components of PN but have to be infused with a filter (usually 1.2 micron).

Check triglycerides (goal TG <200 mg/dL).

Patients on propofol may not need many/any lipids since propofol = 1.1 kcal/mL of fats!

CARBOHYDRATES (provide 3.4 kcal/gram) - Make up the difference with sugar!

Carbohydrates are the preferred fuel for the brain and blood cells. So they are the original “brain food”, which is even more reason to eat that pasta you have been craving.

If a patient is diabetic, insulin regimens will need to be adjusted to keep the patient’s glucose under control. You can add insulin to the bag, but if a patient becomes hypoglycemic – you’ve wasted an entire PN bag. Bottom line, just give insulin outside of the PN (regular insulin that is!).

If the patient is not diabetic, decrease the dextrose when the glucose is >180 mg/dL. Studies have shown that patients can easily be overfed if glucose concentrations are too high based on initial clinical assessment. Some clinicians will calculate a Glucose Utilization Rate (GUR or GIR) to determine how quickly a patient is storing/depleting the dextrose. GUR should not exceed 4 mg/kg-min, because fats providing 40 to 60 percent of calories will meet the energy requirements of most critically ill patients.

GUR = [(Rate of PN x % dextrose) / (kg weight x 6)]

4. Estimate the Patient’s Micronutrient Needs

Calcium/Phosphate precipitation

25 mMol/L of phos + Calcium 10mEq/L + 6% amino acids is the maximum. Less than 6% amino acids will increase risk of precipitation.

Sodium

90% of sodium acetate is converted to sodium bicarbonate

70 mEq/L of sodium chloride will generally keep patients normonatremic if they are at goal when initiated on PN

Recommended Maximum Electrolytes

Sodium (Na): 130 mEq/L (that’s pretty salty)

Potassium (K): 80 mEq/L (watch your heart)

Magnesium (Mg): 12-16 mEq/L

Calcium (Ca): 10 mEq/L

Phosphorus (Phos): 25 mMol/L

When to add thiamine, folate, and vitamins?

How about every day? Most are water soluble, and there’s really no such thing as an overdose.

Vitamin K (Hold for patients on warfarin…)

Vitamins: Be Oprah - You get a vitamin! You get a vitamin!

Most institutions have a standard multivitamin (MVI), of which 10 mL generally goes into each bag of PN.

What about the trace elements? Zinc, manganese ,selenium, copper, and chromium

Manganese and copper are metabolized by the liver and trace elements should be omitted if liver function tests are more than twice the upper limit of normal.

Manganese toxicity: Parkinson’s symptoms

Copper deficiency: anemia

Chromium deficiency: glucose intolerance

Selenium deficiency: cardiomyopathy and other muscle pain

Zinc deficiency: alopecia, dermatitis, poor wound healing. Add extra for wound healing or excessive GI losses.

An Example of Calculating Macronutrients for Parenteral Nutrition

Patient 1: 50 year old Female (50kg, 167cm) with ischemic bowel and history of physiologic short gut syndrome admitted for malnutrition. Patient has multiple decubitus ulcers/sacral wounds. We already determined her fluid needs are ~2000 mL/day and her metabolic needs are ~1500 kcal/day.

Proteins: 1.5-2 g/kg (based on wounds)

1.5*(50 kg) – 2*(50 kg) = 75 - 100 g protein/day

75 - 100 g protein/day * (4 kcal/g) = 300-400 kcal/day from protein

Fats: 250 mL bag of lipids/day * 2 kcal/mL = 500 kcal/day from fat

Carbohydrates: 1500 kcal/day – kcal protein – kcal fats = kcal of dextrose needed

1500kcal – 400 kcal protein – 500 kcal fats = 600 kcal dextrose

600 kcal dextrose/(3.4 kcal/g dextrose) = 176 g dextrose needed

176 g dextrose/2000mL * Xg/100mL (cross multiply and solve for X) = 8.8% dextrose

GUR: [85 mL/hr x 8.8%]/[50 kg x 6] = 2.5 mg/kg-min (which is less than the max of 4 for GUR)

Note: You may need to start with lower glucose and work up to goal to prevent refeeding syndrome depending on how long patient has been without adequate nutrition.

5. Estimate Rate of Infusion for Parenteral Nutrition

To determine rate of PN, use your fluid volume requirements from step 1, divide by 24 hours in a day, and now you have your PN rate in mL/hr.

But you can’t just start with that. Sorry.

When you determine a rate, start low and go slow. Initiate PN at 25mL/hr for 8 hours, increase by 25mL/hr every 8 hours to the final goal rate. Don’t mess this up, you’ll end up spending the next few days treating refeeding syndrome (significant, quick drops in K, Mg, and Phos) and be really mad that you gave them too much sugar. Start your first PN bag with a low dextrose solution.

6. Come up with a Parenteral Nutrition Plan!

No one benefits if PN is forever. At some point the patient and PN have to go their separate ways, and you need to discuss how you are going to get the patient some rebound nutrition or their gut’s hypothetical heart will be broken. Taper PN to 50% for 2-4 hours, then discontinue.

Start tube feeds if the patient cannot eat with a fork! Start the tube feeds slow and advance to goal over 24-48 hours. Remember - they have not used their GI tract while getting PN!

Parenteral Nutrition Summary

Parenteral nutrition is only complicated because there are so many moving parts, but if you take it step by step and continue to practice, you’ll be a Culinary Bag of Liquefied Hospital Burgers Genius.

Be aware that sometimes other clinical thinking scenarios occur that may cause minor changes. For example, continuous renal replacement (CRRT) patients require increased protein (up to 2.5 g/kg/day). Liver disease and glucose metabolism may be affected. Refeeding syndrome often complicates the picture, which is why electrolytes should be replaced aggressively for the first three days that a patient is receiving PN.

I hope these pearls and guidance can help you to make the best decisions for your patients. Remember: This is NOT an emergency, this does not save lives, and this is not an alternative to enteral nutrition.

You’re like, total TPN expert now, right? But what happens when you don’t have internet access in the dank, windowless basement that you call a hospital pharmacy? Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. If you’d like a downloadable (and printer-friendly) version of this article, you can get one here