Rebalancing with Antipsychotics

A note from the tl;dr team: This article was first written by Dr. Prather in 2019. While her original insights remain valuable, guidelines evolve over time. The content was reviewed and updated in September 2025 to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Steph’s Note: Today we’re going to try to make some sense of a class of medications that sometimes just doesn’t make sense. They don’t fit in nice boxes, and predicting response rates is…murrrrky. What class of medications? The antipsychotics! (Yes, you’re right, antidepressants would have also been a legitimate answer here, but check out this tl;dr post about depression to sort those medications.)

Even though these can be daunting to try to learn, there are some patterns we can establish to help start grouping characteristics. And here to help you recognize these trends and patterns is Dr. Caitlin Prather.

Dr. Prather is the inaugural PGY-2 Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Resident at Inova Health System in Fairfax, VA. She received her PharmD from Auburn University and completed her PGY-1 Pharmacy Residency with Auburn University Pharmacy Health Services. She is an active member of the American Pharmacists Association and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Her professional interests include academia and outpatient chronic disease state management including diabetes, HIV, and anticoagulation. Outside of pharmacy, she loves reading, cross stitching, and taking pictures of her two cats (Padme and Winston).

Alright, time to straighten out these confusing medications!

Would you like to print this article? Or save it for offline viewing? You can get it as an attractive and printer-friendly PDF right here.

Unfortunately, you can’t just fully understand schizophrenia by watching A Beautiful Mind…

Or that one episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia…

(Image)

To help clear things up a bit, I’ve tried to compress antipsychotics for you. Antipsychotics is a VERY broad term for a class of medications that is used in the treatment of a variety of psychiatric disorders. These can include anything from schizophrenia to depression to bipolar to even hospital delirium!

How can one class of medications be used in so many different ways?

The Chemistry of Psychiatry

It is thought that many psychiatric disorders are the result of an imbalance in neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are the chemicals that zoom around the brain sending messages from neuron to neuron. The primary neurotransmitters that are out of whack in these conditions are dopamine and serotonin, but others such as GABA, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and glutamate are also implicated. The exact influence of each of these neurotransmitters in psychotic disorders isn’t completely understood, but one longstanding hypothesis (aptly named The Dopamine Hypothesis - cue booming music) is abnormal hyper/hypoactivity of dopamine (and/or its receptors) in specific parts of the brain.

The goals of psychiatric treatment are to decrease symptoms, improve quality of life, improve patient functioning, and minimize medication side effects.

If you have the time, check out this video from the LEAP Institute about living with schizophrenia. (It’s never a bad idea to step into someone else’s shoes to try to understand, especially our patients. Remember empathy?)

Symptoms of psychiatric disorders can be grouped according to the below table:

Antipsychotics primarily target positive symptoms. Negative symptoms may improve with pharmacotherapy but will take longer to respond to antipsychotics, IF they respond at all.

The purpose of antipsychotic medications is to regulate the activity of dopamine and/or serotonin in the brain. There are two major classes of antipsychotics: first generation (FGA) and second generation (SGA).

MOA = mechanism of action; D2 = dopamine-2 receptors; 5HT2A = serotonin 2A receptors; EPS = extrapyramidal symptoms

A Little More about First Generation Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics are also dubbed “conventional” or “typical” antipsychotics or “neuroleptics”.

The most commonly utilized FGA is haloperidol (Haldol®), but this class also includes several others.

MOA: antagonize dopamine activity at D2 receptors

Higher potency antipsychotics have greater affinity for D2 receptors and less affinity for other receptors (such as serotonergic, cholinergic, histamine, alpha, etc.)

High potency:

Examples: haloperidol, fluphenazine, pimozide, thiothixene

Characteristics: higher affinity for D2 receptors

Side Effects: high risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS), such as parkinsonism, acute dystonia, and tardive dyskinesia

Moderate potency:

Examples: perphenazime, loxapine

Characteristics: moderate affinity for D2 receptors

Side Effects: balance between high potency and low potency first generation antipsychotics

Low potency:

Examples: chlorpromazine, prochlorperazine (but wait, that’s an antiemetic!), thioridazine

Characteristics: lower affinity for D2 receptors but higher affinity for cholinergic receptors

Side Effects: high risk for anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, urinary retention, constipation), sedation, and hypotnesion

FGA are generally reserved for refractory or emergent cases due to associated adverse effects

Moving on to the Second Generation Antipsychotics

The SGA, also known as “atypical”, are generally used first line for chronic management of psychosis. They were originally developed to reduce the EPS symptoms that are commonly seen with FGA, and many studies have shown comparable efficacy between FGA and SGA. So some wins for safety and adverse events, hopefully without sacrificing efficacy!

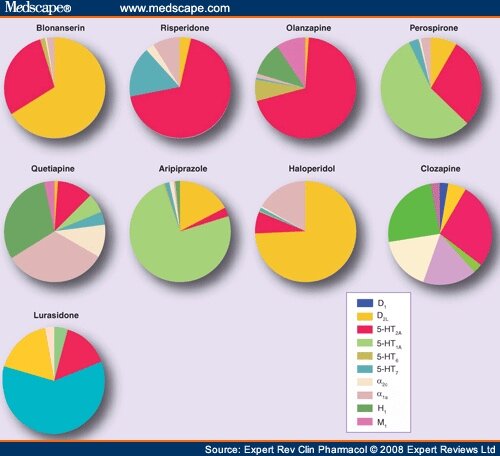

MOA: well, this is a bit of a loaded point… Check out all the various receptors affected by just some of the SGA:

Receptors in order from left to right: dopamine-2 antagonism, dopamine-2 partial agonism, dopamine-3 receptor, serotonin-1A partial agonism, serotonin-2A antagonism, serotonin-2C, serotonin-7, alpha-1 receptor, alpha-2 receptor, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Receptors not even listed but also known to be affected: histamine and muscarinic/acetylcholine.

So yeah, pretty difficult to keep straight what receptor is being affected, let alone whether it’s being agonized or antagonized. And THEN what the effects of those actions are!

(Image)

Another pretty cool visual for grasping the extreme variety in MOAs with the antipsychotics. Each is just a smidge different when it comes to which particular receptors are affected… (Image)

Examples of SGA: aripiprazole (Abilify®), asenapine (Saphris®), brexpiprazole (Rexulti®), cariprazine (Vraylar®), clozapine (Clozaril®), iloperidone (Fanapt®), lumateperone (Caplyta®), lurasidone (Latuda®), olanzapine (Zyprexa®), paliperidone (Invega®), pimavenserin (Nuplazid®), quetiapine (Seroquel®), risperidone (Risperdal®), and ziprasidone (Geodon®)

Unlike the FGA, the SGA can’t really be classified by potency per se. However, there are some unique points for each that help to distinguish the SGA a little bit from one another. Notice how some of these traits can be tied back to the specific receptor profile of the drug!

Aripiprazole

Slightly different MOA from other atypicals. Note how in the above rainbow mechanism chart, aripiprazole is a partial agonist of both D2 and 5HT1, while also antagonizing 5HT2

The combination of partial D2 agonism in some parts of the brain with D2 antagonism in other parts of the brain is thought to reduce the EPS side effects that arise from full dopamine antagonism - while still providing the desired antipsychotic effects

Ziprasidone

While the majority of second generation antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation, Ziprasidone is by far the biggest offender. In fact, clinical trials have shown that the average increase in QTc following oral ziprasidone was approximately 5 to 23 ms. Some literature even shows cases of torsades de pointes. Moral of the story, get an EKG before starting ziprasidone.

Olanzapine

Structurally similar to clozapine but without the risk for agranulocytosis (a-what? more in a sec)

Has significantly more metabolic side effects than most of the SGA

Quetiapine

Moderate risk of metabolic effects and prolonged QT interval

Quetiapine (and clozapine) are the only true “atypicals”. Meaning that they carry the lowest risk for EPS compared to other first and second-generation antipsychotics

Higher doses (usual range of 400-800 mg/day) are generally needed to provide schizophrenia treatment

Risperidone

Considered to be one of the most “typical” of the atypical antipsychotics. Meaning out of all the second-generation antipshychotics, risperidone carries that highest risk for EPS

Known to increase prolactin levels leading to gyencomastia

Paliperidone:

Paliperidone is the major active metabolite of risperidone. Meaning the body metabolizes risperidone into paliperidone (remember prodrugs?). So yes, they share a pretty similar side effect profile

Also known to cause EPS (however, not as much as risperidne)

Known to increase prolactin levels leading to gynecomastia

Clozapine – the good, the bad, and the ugly

(Image)

The good: it’s pretty dang effective

Clozapine is a very effective antipsychotic

Only indicated for schizophrenia but may be used off-label for agitation or bipolar disorder

Clozapine is generally not recommended until patients have tried 2 different monotherapy antipsychotic trials due to clozapine’s safety concerns and monitoring

Much like quetiapine, clozapine is a true atypical and has very low risk for EPS compared to all other antipsychotics

The bad: Higher risk for sedation, anticholinergic effects, hypersalivation, orthostatic hypotension, nausea/vomiting, and weight gain

Lowers seizure threshold more than other antipsychotics

The ugly: Black Box Warning for severe neutropenia (agranulocytosis)

Severe agranulocytosis is potentially fatal

Occurs most commonly in the first few months of treatment

ANC = Absolute Neutrophil Count = total WBC count x total % of neutrophils from CBC

Check weekly for first 6 months, every 2 weeks for months 6-12 of treatment, and every 4 weeks after 12 months of clozapine treatment

Goal is for ANC to stay >1500

Note: patients with Benign Ethnic Neutropenia (BEN) will have different thresholds and monitoring parameters

If mild neutropenia occurs (ANC <1000) – can continue treatment but increase monitoring

If severe neutropenia occurs (ANC <500) – discontinue treatment and only re-challenge if benefits significantly outweigh risks

As of February 24, 2025, the FDA removed clozapine from Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program because the agency determined the REMS was no longer necessary to ensure the drug’s benefit outweighed its risk. However, the risk for neutropenia is still very major and clinically relevant. Removal from REMS does NOT mean we should stop monitoring neutrophils.

Other Considerations for Antipsychotic Therapy

Many of the SGA (and even haloperidol) are available as long acting injectables (LAIs)

Advantages

Help to improve adherence to medications, which can be especially helpful in a patient population with non-adherence rates estimated as high as 50%

Usually as efficacious as their oral equivalents

Disadvantages

Some require an overlap period with the oral formulation while the injection is “kicking in”

Due to long duration of action, if side effects do occur then patient has to deal with them for longer period of time

Potential for injection site reactions

SALAD (Sound Alike Look Alike Drug) issues

For example, haloperidol lactate is the normal immediate release injection whereas haloperidol decanoate is the long acting formulation. Double check those orders!

To get an idea of how these SGA are available (and how hard it can be to keep up with all the different formulations!), here’s a mere taste of dosage forms and pearls:

Of note, this table is not 100% comprehensive on dosage forms (believe it or not), but it does represent some of the most commonly used forms as well as some pearls to log away!

(Image)

Acute intramuscular injections (for “stat” relief)

Some antipsychotics can be used for an acutely agitated and psychotic patient if they are immediately at risk of harming themselves or others

Fast acting injectable options include haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, and olanzapine

Often given with other medications (e.g. “the Haldol cocktail” or “B52” which contains Benadryl (diphenhydramine), haloperidol 5mg, and lorazepam 2mg). One cool nerdy fact to remember. The Benadryl and lorazepam in that mix do provide sedation which is generally needed for severely agitated patients. But they also help combat the EPS side effects for haloperidol. A 2-for-1 special :)

Of note, parenteral olanzapine carries a warning against concomitant use of parenteral benzodiazepines due to a reported (but unproven) risk of death

Adverse Effects of Antipsychotic Medications

While antipsychotics can be very effective at controlling symptoms for many patients, they also come with their fair share of side effects. It’s important to remember the receptor binding profiles of these medications, since actions at those receptors are often responsible for the medications’ adverse effects!

Some of these were discussed above, but I’ve also included this handy chart for you to see many of the antipsychotics side by side:

EPS/TD = extrapyramidal symptoms/tardive dyskinesia; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus

Again, this chart is not all-inclusive, but it contains many of the most commonly used antipsychotics.

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS) and Tardive Dyskinesia (TD)

EPS symptoms include akathisia (inability to sit still or a feeling of restlessness), bradykinesia (slow body movements), dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and tremor. These symptoms are the result of dopamine antagonism since dopamine is involved in the control of muscle movements (think about how we treat Parkinson’s Disease…)

Tardive dyskinesia includes involuntary movements of the mouth, tongue, face, and sometimes the extremities as well. Unique movements you might encounter are lip-smacking, facial grimacing, and tongue rolling. These can range from just mild and annoying to severe and disabling. They can also be IRREVERSIBLE! Monitor with assessments such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) to track development and progression of symptoms.

Like was mentioned before, one of the main reasons the SGA were developed was to reduce the incidence of EPS and TD. Since the SGA act on dopamine and serotonin receptors, and some of them are even partial dopamine agonists rather than only antagonizing dopamine like the FGA, there is generally less EPS and TD with these agents. But as seen in the above videos, these adverse effects are still very real with the SGAs.

The highest risk is with FGA like haloperidol and fluphenazine. Of the SGA, the greatest risk is seen with risperidone (remember it’s the most "“typical of the atypicals”) and paliperidone. The lowest risk is associated with quetiapine, pimavanserin, and clozapine.

Treatment: Depending on the severity of the EPS or TD, it may be appropriate to treat the side effect with another medication, or it may be necessary to switch to a different antipsychotic altogether.

Trials of beta blockers (particularly propranolol) or anticholinergics (like benztropine) may help with akathisia. Benzodiazepines are alternative treatment options.

Parkinson’s-like symptoms such as resting tremor and bradykinesia can be managed with benztropine or amantadine. The prophylactic use of anti-parkinsonism agents is generally not recommended but is sometimes used in patients on high doses of high-potency, FGA (e.g., haloperidol >10 mg/day).

Dystonias can be treated with benztropine or diphenhydramine.

Valbenazine (Ingrezza®) and deutetrabenazine (Austedo®) can be useful in treating tardive dyskinesia.

Metabolic Abnormalities

This usually refers to the triad of dyslipidemia, weight gain, and hyperglycemia. These adverse effects are associated more with the SGA than first generation medications. The greatest risk is with clozapine and olanzapine, and the lowest risk is with aripiprazole, lurasidone, pimavanserin, and ziprasidone.

Guidelines recommend both short- and long-term monitoring of weight, blood pressure, glucose, and lipid profiles for patients on any antipsychotic.

Treatment: Similar to EPS/TD management, metabolic abnormalities can be managed with additional pharmacotherapy or by trying an alternative antipsychotic. There is no major difference in treating a patient on an antipsychotic for these abnormalities compared to patients not on antipsychotics (e.g., use a statin for dyslipidemia, metformin for type 2 diabetes, etc.)

Elevated Prolactin Levels (Hyperprolactinemia)

Dopamine is one of the main neurotransmitters that controls prolactin secretion at the pituitary gland in both men and women. By blocking dopamine receptors, antipsychotics can cause uninhibited secretion of prolactin.

Consequences of elevated prolactin include sexual dysfunction, gynecomastia (sore, tender, enlarged breasts in both men and women), and galactorrhea (nipple discharge).

Anticholinergic Effects

Remember S.L.U.D.G.E. from P1 year?? Salivation, Lacrimation, Urination, Defecation, Gastric upset, Emesis… All of those things are decreased when there are anticholinergic side effects. (Anticholinergic side effects can also be beautifully summarized as: can’t see, can’t pee, can’t spit, can’t sh*t.)

The rare exception to this is that clozapine actually commonly causes sialorrhea (excessive salivation) rather than dry mouth.

For most patients, these side effects are not dangerous, but they can be unpleasant and potentially lead to nonadherence. When they do become dangerous is in our elderly patients, for whom changes in vision or urinary/bowel habits can lead to falls or infections. Check the Beer’s List for anticholinergic meds!

Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostasis refers to the body’s attempt to compensate blood pressure for a sudden change in position. This mechanism is controlled by the autonomic system in response to becoming upright. So changing from lying down to sitting or sitting to standing can trigger this response.

Orthostatic hypotension is when a person’s blood pressure doesn’t adequately change when changing position, leading to drops in blood pressure and potentially a DFO. That’s a “done fell out” - or a syncopal event - or a faint.

This adverse effect is most frequently seen with clozapine, quetiapine, and paliperidone, probably at least in part due to their affinities for the alpha receptors. (Remember alpha antagonists like doxazosin or prazosin cause drops in blood pressure?) The lowest risk of orthostatic hypotension is with aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, and lurasidone.

QTc Prolongation

QTc prolongation refers to an extension of the interval between the start of the QRS complex and the T wave on an EKG. There’s QT and then QTc, which is just a calculated/corrected version.

We all kinda freak out above very long QTc intervals because they can predispose patients to fatal arrhythmias, specifically Torsades de Pointes. So what is “very long”?

(Image)

A QTc over 500 milliseconds is DEFINITELY very long. A QTc between about 470 and 500 ms means you need to have a reeeeeally good reason to use your chosen medication, and please do assess for other compounding offenders for QTc prolongation. Make sure your patient’s potassium and magnesium levels are replete to try and protect against arrhythmias.

Ziprasidone is one of the worst SGA for QTc prolongation. But it’s not really alone. Quetiapine, paliperidone, olanzapine, and risperidone are also offenders to watch closely.

Lurasidone, aripiprazole, and brexpiprazole seem to have the least QTc prolongation of the SGA.

Use of Antipsychotics in the Elderly

All of the SGA carry a Black Bow Warning regarding the increased risk of death in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis - and this risk applies to FGA as well.

Seems like a bit of a catch 22, right?

Elderly patients with dementia often have psychotic symptoms related to their disease process - hallucinations, delusions, agitation, and depression. For example, in Lewy Body Dementia, it’s estimated that up to 85% of patients experience visual hallucinations (interestingly, often of small children or animals). For their own comfort as well as to help others successfully care for them, it may be necessary to try patients with dementia on an antipsychotic medication.

Regardless, it’s been shown that this combination of medication and patient population results in a 1.5-1.7 times increased risk of death. So choose wisely and only after other options, including non-pharmacologic, have been considered or tried.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

This is a quite rare adverse effect of antipsychotic medications - but it’s worth knowing about since it can be lethal. As such, just log away that NMS is a MEDICAL EMERGENCY.

(Image)

Although the full pathophysiology is not really understood, it IS known that this constellation of symptoms seems to arise from a lack of dopaminergic activity. So all these antipsychotic medications that block dopamine at its receptors? Yep, implicated.

(Interestingly, NMS can also arise when dopamine supplementation is abruptly ceased, such as when levodopa treatment for Parkinson’s disease is discontinued. So that also seems to lend credence to the whole sudden-cut-off-of-dopamine hypothesis.)

There’s also the possibility that both the sympathetic nervous system and the calcium flux in the skeletal muscle system are involved.

Signs and symptoms of NMS include fever, muscle rigidity, altered mentation (may range from mild confusion to full on coma), tachycardia, labile blood pressure, sialorrhea (drooling), flushing, diaphoresis (sweating), incontinence, increased CPK, and increased WBC.

NMS usually occurs within a couple of weeks of starting an antipsychotic medication or after increasing doses, but it can also occur years later. Be cautious about speed of the titration as well as when switching between medications!

Treatment of NMS includes stopping the suspected offending medication as quickly as possible, providing supportive care (is the patient managing his own airway? does he need hydration to flush the CPK and protect the kidneys?), and cooling the patient. Pharmacologic therapy often includes bromocriptine (a dopamine agonist) to reverse the hypodopaminergic state induced by the antipsychotic. Dantrolene (a muscle relaxer) may help with the muscle rigidity, but use caution since it can cause hepatotoxicity! Benzodiazepines may also help with agitation.

SUMMARY

SoOoOooo…

How do I know which antipsychotic to use?

In general, start with a second-generation antipsychotic, considering the individual patient and the potential side effects (based receptor binding profile!) of each medication

If a patient is underweight, maybe the metabolic side effects aren’t as worrisome compared to an overweight patient who has comorbid T2DM. For the underweight patient, olanzapine may be an appropriate option despite its metabolic effects.

If a patient has very poor adherence, choosing an agent with a long-acting injectable formulation may be helpful. Aripiprazole could be a good choice for this patient since it’s available as a once monthly injection.

Save clozapine for last line… it’s very effective but requires extensive and strict monitoring due to risk for severe agranulocytosis

Cost may be an issue for some agents that are newer or have unique dosage forms (e.g., the injectables)

It may take a few medications with trial-and-error to find the right regimen for each individual patient - monitor closely and stick with the lowest effective dose!