New FDA Approvals: The Year of NMOSD

Steph’s Note: It’s been a couple of weeks since we’ve had a clinically-minded post, and it’s also been a hot minute since we’ve discussed new medications on the market. So we’re going to tackle both of these aspects in triplicate - because 2020 was the “year of NMOSD.”

This may sound super nerdy, but when you get a single new drug for a rare disease state, that’s exciting in and of itself. But two drugs in one year!? Whaaaat!??! (And really, including 2019, it’s three drugs in two years!)

Color me pumped!

Plus, it’s always fun to learn a little about a new disease state that, sure, you may not encounter every day. But when you do, you’ll at least have an inkling of what it means for your patients. So let’s dive into NMOSD!

What is NMOSD?

NMO, or NMOSD, stands for Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. (A more historical name for this is Devic’s disease - save that for trivia night because you probably won’t need it anywhere else.) NMOSD refers to a cluster of phenotypes characterized by demyelination within the central nervous system (CNS) that is considered autoimmune. It has a prevalence of 0.5 to 10 cases per 100,000 in the US, affects females more often than males, and typically has an onset age of between 35-45 years. Sounds a bit like multiple sclerosis (MS), doesn’t it?

Well that used to be a huge confusing problem because MS and NMOSD definitely share some similarities. (NMOSD was actually originally thought to be a subset of MS, although it is now recognized as its own entity.) Like many patients with MS, NMOSD is clinically characterized by episodes of:

Optic neuritis (ON), which is inflammation of the optic nerve causing pain inside the eye and vision loss (up to blindness), and/or

Transverse myelitis (TM), which is inflammation of the spinal cord causing pain in the spine or limbs and loss of function (up to paralysis).

These episodes can recur leading to a relapsing phenotype, although the time frame of recurrence is highly variable (weeks...months...years...decades even!).

So what’s the difference?

Epidemiologically-speaking, NMOSD is 50-100 times less common than MS in the US with only an estimated 4000 people in the US currently diagnosed with NMOSD. Age at MS onset is also a little lower (25-35 years) than NMOSD, although both are more common in females than males. Clinically-speaking, in NMOSD, the episodes of ON or TM are often more aggressive than in MS, and they actually can be fulminant - meaning acute, complete failure. It’s estimated that, if left untreated, about 50% of NMOSD patients will become fully blind and dependent on a wheelchair, and about a third will die within 5 years of their first episode.

So perhaps not very common. But certainly scary, isn’t it.

There are also different MRI findings in NMOSD compared with MS. Contrary to MS, NMOSD patients do not usually have too many white matter lesions on brain MRI, but they often have longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) evidence in 3 or more spinal vertebral sections. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from a lumbar puncture demonstrates high leukocyte counts (elevated >50), with or without neutrophils, and usually without oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in NMOSD, whereas OCBs are found in ~80% of MS patients’ CSF.

And finally, the relatively new kid on the block identified just a few short years ago in 2004 that REALLY helps with differentiation of these distinct disease states?

(Image)

The NMO antibody. Aka, the NMO-IgG or anti-AQP4.

This is where the autoimmune piece really plays in. For reasons yet unknown, some people produce pathogenic antibodies against the aquaporin-4 protein (AQP4) found on astrocytes, which are CNS cells responsible for multiple functions like water and ion homeostasis and tissue recovery after insult or injury. But just to make things more complicated, not every person diagnosed with NMOSD is positive for the NMO-IgG… About 75% are, but there’s a subset of patients who are seronegative and still meet clinical criteria for NMOSD.

Some patients who are NMO-IgG negative test positive for a different antibody: the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody. FYI, this is another reason why it’s called NMOSD - there is certainly a spectrum of demyelinating phenotypes encompassed by this term, and therapy for patients positive for MOG is distinct from that of patients seropositive for NMO-IgG. (In fact, MOG-associated disorder - or MOGAD - is increasingly being recognized as a distinct entity even from NMOSD, but this kind of depends on who you talk to.)

So, to (try to) summarize the diagnostic criteria for NMOSD…

(Image)

Now that we know a little bit about this scary, acute onset, possibly painful demyelinating disease, what options do we have for treatment?

Management of Acute NMOSD Attacks

Regardless of NMO-IgG or MOG-Ab serostatus, patients experiencing NMOSD acute attacks of ON or TM are managed the same way. High dose steroids with or without plasma exchange are used to shift the balance from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory and remove the offending auto-antibodies from circulation, respectively.

When we say high dose steroids, we mean HIGH dose. We’re talking intravenous methylprednisolone 1000mg daily for ~5 days in a row. The goal of this is to halt the inflammation as best as we can since prolonged inflammation means increased likelihood of permanent damage and disability. For some patients who are unable to make it to an infusion center, there is the potential option of giving these steroids orally. But it’s not exactly fun.

The oral equivalent is prednisone 1250mg by mouth daily for ~5 consecutive days.That comes to 25 of the 50mg tablets EVERY day for at least 5 days. (Yeah, I kinda freaked out the first time I saw that prescription too...but it is in fact intentional!)

I don’t know about you, but taking 25 tablets of anything doesn’t sound appealing, let alone steroids. This is usually broken up into 9 tablets in the morning with breakfast, 8 tablets at an early lunch, and 8 tablets in the afternoon, which avoids the patient taking doses close to bedtime since you can imagine insomnia is one of the expected adverse effects of this regimen. Patients may want to use OTC diphenhydramine to help combat this. It’s also kind to prescribe patients a short supply of famotidine, an H2-receptor antagonist, to accompany this prednisone course to help protect the stomach lining from steroid-induced irritation.

For NMOSD, patients usually undergo a very long, very slow taper after this initial high dose steroid course. This taper can range up to 6 months (and sometimes more), depending on whether symptoms recur with dose decreases as well as choice of chronic NMOSD therapy. So don’t forget to monitor for all the long-term steroid adverse effects:

hyperglycemia and weight gain (caution diabetics),

sodium and fluid retention (caution CHF and renal patients),

osteoporosis, and

immunosuppression (depending on dose and duration).

Let’s take a brief moment for the other possible arm of acute NMOSD management: PLEX, aka plasma exchange or plasmapheresis. (This was not a modality I remember being exposed to in pharmacy school, so by reading this, you’ll be a step ahead!)

The circuit of PLEX. (Image)

Somewhat similar to hemodialysis, PLEX uses a machine to remove blood from a patient, centrifuge it into cellular components versus plasma, and then reinfuse the cellular components back into the patient along with a replacement colloidal solution. The colloidal solution (often a combination of albumin and fresh frozen plasma) is used to replace the patient’s plasma, which is not reinfused since it contains the reactive auto-antibodies causing the problem.

Pretty crazy that this is possible, right?

Even though it’s mechanistically a useful strategy, it comes with its own baggage. Like other procedures that rely on lines and external machines, infection is a risk. Hemodynamic shifts can be intolerable for some patients, leading to each exchange cycle being prolonged or spaced out in order to make them tolerable. Removal of anticoagulation factors by PLEX and subsequent repletion of short half-life procoagulant factors first can lead to thrombosis, making heparin anticoagulation a necessity.

And finally, we’re pharmacists, so we have to consider how PLEX may affect drug concentrations. (Nope, hemodialysis isn’t the only procedure we have to consider when it comes to drug PK!) Medications that are highly protein bound with low volumes of distribution can be removed by PLEX, so timing of medication administration after PLEX or administration of extra replacement doses after PLEX may be necessary.

So given the complications associated with PLEX, it’s not necessarily used for all NMOSD patients with acute attacks, even though some case series have demonstrated clinical benefit in disability improvement with the combination of steroids + PLEX rather than steroids alone. In the case of NMOSD, PLEX is generally used if a patient is intolerant or refractory to high dose steroids. But in true form with this phenotypically diverse disease, it’s relatively subjective as far as what qualifies as a severe enough attack to warrant PLEX or what is defined as a refractory case. How long should steroids be tried before deeming them insufficient?

So much left to learn.

Prevention of NMOSD Relapses

Now that we’ve covered options for quieting down acute NMOSD (and MOGAD) attacks, it’s time to move onto how we can try to prevent these episodes from recurring. There are a number of medications that have demonstrated at least some utility here, but most (i.e., all but 3) of these medications are off-label for NMOSD. Plus, they’re kind of mixed bags.

First Generation Therapies for NMOSD

Yes yes, I know this is a new drug update post, and I promise we are going to get to the new, FDA-approved therapies. But context matters!

For many patients in years past, the only options available to them for preventing NMOSD relapses were some fairly old-school medications. Options included several anti-proliferative medications, which through various mechanisms prevent proliferation of B and T cells. These included azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and (gasp) cyclophosphamide even! These relatively non-targeted treatments come with risks of significant adverse effects, up to and including risk of malignancies.

Not exactly first choices, although they can be tried in any NMO patient regardless of antibody serostatus.

(Image)

So then the world progressed to slightly more refined therapies in the forms of rituximab and tocilizumab. Again, these aren’t approved for use in NMOSD, but evidence has demonstrated potential benefits. Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that leads to B cell depletion, has been used in variable dosing regimens with seeming benefits in reducing annualized relapse rates. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, also recently demonstrated decreased annualized relapse rates and prolonged time to first relapse compared with azathioprine in the 2020 TANGO study.

So perhaps you can teach some old dogs new tricks! Some of these older monoclonal antibodies can be repurposed for new indications.

But perhaps we can do even better - with truly targeted therapies.

New Generation Therapies for NMOSD

NOW we come to the new drug update portion of this post. See, I promised :)

2019 and 2020 were truly the years of NMOSD. For such a rare disease state to have THREE therapies approved for use in this short amount of time is pretty incredible. So let’s take a closer look at each of these 3 treatments.

Eculizumab (Soliris) for NMOSD

It’s possible you’ve run across eculizumab in other contexts than NMOSD. It previously earned FDA labeled indications for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), refractory myasthenia gravis, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, but in 2019, it added NMO-IgG+ patients to its list of approved uses.

Ok, so those other indications are also fairly obscure… but maybe you ran across an aHUS or myasthenia case on internal med. Maybe. It’s ok if you haven’t, just hold tight, that’s the beauty of internal med!

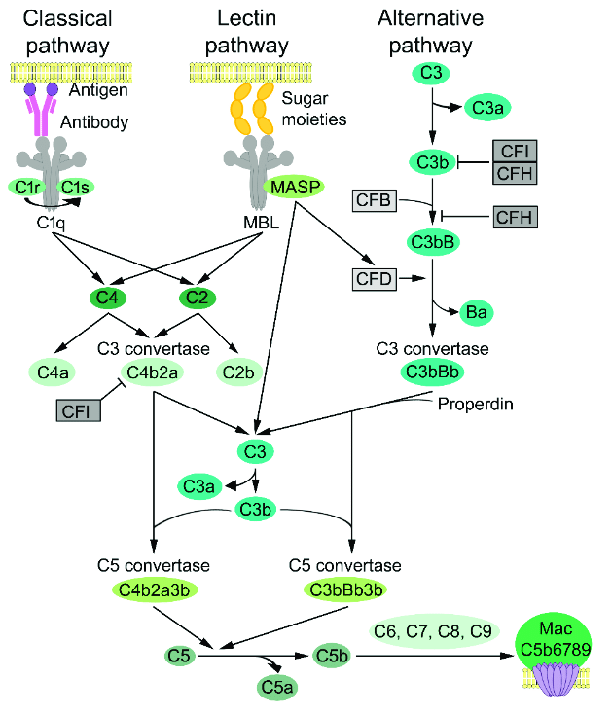

Eculizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to complement protein C5, inhibiting further complement cascade. It’s not totally clear exactly how this helps in NMOSD, but inhibition of the complement cascade is thought to interfere with the NMO-IgG’s activity.

The complement cascade. It’s ok, it’s natural to feel panic when you see this gem. What I mostly want you to notice here is that conversion from C5 into C5a and C5b is the FINAL step in the cascade before formation of the MAC - membrane attack complex. So eculizumab’s action is to stop this final cascade step. (Image)

For those of you who hated learning the coagulation cascade, you ain’t seen nothing yet. This one’s worse...sorry. Check out the cascade here.

The 2019 PREVENT study compared eculizumab to placebo in 143 patients who were NMO-IgG+. Eculizumab patients experienced a significant reduction in NMOSD relapses compared with placebo (3% vs 43%, HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.02-0.20). Of note, concomitant, stable immunosuppressive therapy, including azathioprine or mycophenolate with or without steroids (or steroids alone), was allowed in both comparator groups.

Slightly more patients in the placebo group were not on immunosuppressive therapy compared with the eculizumab group (28% on none vs 22%), but that slight difference probably wasn’t sufficient to drive such a drastic difference in the primary relapse outcome.

With such an impressive primary outcome difference, there can’t possibly be any downsides to this therapy, can there?

Welllll, of course there are. This isn’t utopia.

So first, let’s talk dosing. Eculizumab is administered as 900mg IV weekly for the first 4 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 1200mg every 2 weeks starting at week 5. Luckily it’s a pretty short infusion, usually 35 minutes in adults (no more than 2 hours).

So once the patient gets to the infusion center, they at least don’t have to stay the whole day like some other medications. But still every 2 weeks is a pretty intensive regimen to stick to. Imagine trying to plan vacations or work… I feel like I can barely make my annual PCP appointment, but you do what you gotta do.

If a patient happens to require PLEX during eculizumab therapy, dosage adjustments and replacement doses have to be considered as it is removed by that procedure. So that’s another ripple. Not terrible - and definitely manageable - just a ripple.

Next, the biggest warning associated with eculizumab is the risk of meningitis. This is actually an FDA black box warning because the risk of meningitis is increased up to 2000 times the normal population.

Whoa. Did I just say 2000 times?!? Yeah. THAT kind of warning.

So in addition to the black box warning, there’s also a REMS program creatively dubbed the Soliris REMS. For this program, only the prescriber (not the patient) has to be registered, and that’s because the program’s goal is for providers to address meningitis vaccinations and/or prophylaxis prior to initiating a patient on eculizumab.

For a quick refresher on meningitis vaccines, check out the chart below. Essentially the basics are that there are 2 sets of vaccines available: one for Neisseria groups ACWY and one for group B. Patients starting eculizumab should be vaccinated with one from each class at least 2 weeks prior to therapy start, and then (gasp) they need to finish the series - and receive boosters!

Enter the pharmacist. This is our bread and butter. We can make sure patients are scheduled for follow up doses, that the time intervals and formulations are appropriate, and that boosters are tracked as long as the patient’s meningitis risk persists.

Seems pretty straightforward, but of course, there’s still a ripple. In a 2017 MMWR report of eculizumab patients in the US between 2008-2016, 16 cases of meningitis were reported. Fourteen of these cases had received at least 1 dose of a meningococcal vaccine prior to eculizumab initiation, but 11 of the cases were caused by nongroupable Neisseria meningitis.

Well darn, the vaccines don’t cover all the possible Neisseria pathogens. Crud.

This is why some clinicians choose to also provide short (or even long) term antibiotic prophylaxis for meningitis with options like penicillin, erythromycin, or ciprofloxacin. You can imagine the pros and cons of using each of these antibiotics, especially when considering long-term use (eek), so this is not a decision to be made lightly. Think resistance, renal impacts, joints, GI, and the list goes on… But just know this is also possible.

So that’s eculizumab, targeted option #1 for NMOSD patients who are seropositive for NMO-IgG. Let’s go to new drug #2.

Inebilizumab (Uplizna) for NMOSD

Next is inebilizumab, which is a mouthful for sure. In-ebb-uh-lih-zu-mab. Phew.

This medication was approved in June 2020, also for NMO-IgG+ patients. It’s a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against the CD19 antigen on the B cell surface, leading to B cell depletion. Sounds kind of familiar, doesn’t it? Maybe a bit like rituximab?

But wait, rituximab is an anti-CD20 medication! How are these different then if they both affect B cells?

CD19 vs CD20 expression on different B cell subtypes.

CD19 is expressed on a wider array of B cell subtypes than CD20. So for example, CD19 is not only expressed on mature B cells but also on pre-B cells, so inebilizumab would be expected to deplete a wider array of B cell types than rituximab.

Not that these have been directly compared. That would be way too convenient.

Instead, inebilizumab was compared with placebo in the 2019 N-MOmentum study, during which a pre-defined initial 21 day prednisone taper was the only concomitant immunosuppression. The study enrolled 231 patients, of whom over 90% in each treatment group were NMO-IgG+. Over the course of the 197 day trial period, a significant increase in the time to first NMOSD attack was observed in the inebilizumab group compared to the placebo group (12 vs 39%, HR 0.272, 95% CI 0.150–0.496). Like the previous eculizumab trial, this was largely driven by outcomes in the NMO-IgG+ subgroup, which of course was by and far the majority included here.

Inebilizumab is administered as an IV infusion with 300mg doses on days 1 and 15, followed by 300mg every 6 months thereafter. Also sounds a lot like the dosing schemes for our other B cell therapies, like rituximab and ocrelizumab, doesn’t it?

That’s because the pharmacodynamics are somewhat similar. Doses of inebilizumab thoroughly suppressed B cells by week 4 and kept them at levels less than 10% of baseline for the remainder of the 197 day study period. So relatively rapid and persistent B cell depletion.

The most common adverse effects associated with inebilizumab in the N-MOmentum study were infusion reactions (premedications like acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, and methylprednisolone should be used), infections, including UTI/cystitis, and aches/pains. Lymphopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia (low antibody levels), and neutropenia are also possible.

So that’s option #2 for patients who are NMO-IgG+. Still not hitting on too many winners for patients who are seronegative, but at least there are options for what comes to the majority of patients with NMOSD. Now time to move on to the 3rd new drug in 2 years for NMO!

Satralizumab (Enspryng) for NMOSD

So the final drug approved in the “year of NMO” was satralizumab, or Enspryng. It was FDA approved in August 2020 for (you guessed it) NMO-IgG+ patients.

Like its predecessor tocilizumab, satralizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-6 receptor and antagonizes it, which prevents IL-6 mediated signaling. Blocking IL-6 is thought to lead to decreased anti-AQP4 production and secretion, less T cell inflammation by influencing T cell differentiation, and decreased permeability of the blood brain barrier, which may help to prevent so much translocation of autoreactive immune cells into the CNS.

So why satralizumab instead of tocilizumab?

Drum roll…

Home administration, folks! Just like what ofatumumab is doing for the anti-CD20 treatment group in MS, satralizumab offers patients a home administration option of an efficacious medication. It is dosed as 120mg subcutaneously at weeks 0, 2, and 4, followed by a convenient monthly maintenance injection thereafter.

See, even Boromir understands. (Image)

This is pretty exciting, but does the increase in convenience come with a cost? Call me cynical, but don’t nothin’ come without a cost, right?

(Yes, I just double negative-d for emphasis. I think I actually died a little on this inside, but what’s done is done.)

Well let’s take a look at the data. Satralizumab was studied in 2 sister trials. The first was SAkuraSky (weird capitalization = intentional) in 2019, which was the combination therapy trial that compared satralizumab to placebo with both groups also taking concomitant baseline immunosuppressive therapy. The second was SAkuraStar in 2020, which was the subsequent monotherapy study that compared satralizumab vs placebo WITHOUT any concomitant immunosuppressive therapy.

Basically, the first study investigated how well this medication may work when used with other immunosuppressants. Then, they got a little bolder and decided to see how well it would do without any possible masking from other therapeutic medications.

Turns out, not too shabbily, even on its own. Here’s what they found:

IST = Immunosuppressive Therapy

In both studies, there were significant reductions in relapse rates compared with the placebo groups, and these results were maintained throughout the durations of each study (through at least 96 weeks). The benefits were largely driven (again) by the NMO-IgG+ subsets of patients, without the same degrees of benefits seen in the seronegative patients (although the latter groups were also a bit smaller). The use of concomitant immunosuppressants in SAkuraSky also led to fewer satralizumab patients relapsing over time compared with the monotherapy patients in SAkuraStar, but both groups still did way better compared with the respective placebo groups.

Monitoring of satralizumab includes counseling on signs and symptoms of infection. Patients should be screened for latent infections prior to initiation to ensure nothing is going to rear its ugly head after starting satralizumab (things like hepatitis B or tuberculosis). Liver function tests should also be monitored as elevations did occur in studies.

So there you have it. The 3rd medication FDA-approved for NMOSD, when prior to 2019, there were NONE!

But what about those NMO-IgG seronegative patients…

Some, but not all, of the NMO-IgG seronegative patients end up testing positive for the MOG-Ab. Chronic management of these patients is a little different, and we should take a brief moment for their care. For these patients, a recent study published in June 2020 seems to indicate that the preferred medication for this subset of patients is IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin.

Now, again, I don’t remember being introduced to IVIG during pharmacy school, so here’s another leg up!

IVIG refers to multiple products on the market that are composed of donors’ purified antibodies. It takes thousands of donors and almost a year to make IVIG products, which is why these treatments are extremely expensive. They are typically dosed in grams/kg/day and given over several consecutive days.

If possible and there’s time, patients should be screened for latent infections before receiving IVIG products. Because we’re actually giving an infusion of donor antibodies with IVIG, testing patients after they’ve received these products makes it impossible to tell whether any positive results are due to the actual patient’s history of exposure versus the IVIG donors’ history of exposure.

So that’s a bummer if your patient pops positive for hepatitis B core antibodies and you don’t have any historical values to guide whether or not the patient might need prophylaxis against reactivation…

Let the blockers stick to football. (Image)

The other caveat with IVIG is to try and update vaccinations prior to initiation - again, if possible. This one can be a little harder to complete than the baseline labs depending on timeline for IVIG initiation, but it’s still worth mentioning. There’s some thought that if vaccinations are given after a patient receives IVIG that the donor antibodies may bind the vaccine antigens, effectively preventing the actual patient’s immune system from mounting a response.

The IVIG runs blocker for the host immune system. Not helpful in this case.

The last pearl to remember about IVIG products is that not all marketed products are created equally. Because these are donor products and the purification processes are variable, each product differs with regards to:

sugar types and amounts,

sodium content,

osmolarity,

IgA content (possibly related to IVIG hypersensitivity), and

route of administration.

This site from the Immune Deficiency Foundation has a fantastic summary table of available IVIG products and has been incredibly helpful when determining ideal products for individual patient cases (or when writing appeal letters to insurance for non-preferred products). For example, consider whether you would want to use a product with high sodium content in a patient with concomitant congestive heart failure?

For MOG-Ab+ patients who fail or are unable to tolerate IVIG infusions, back up plans include rituximab or some of the first-generation (non-targeted) anti-proliferatives.

The tl;dr of NMOSD

Hopefully this brief window into an uncommon (but very poignant) neuroimmunological disease state has been interesting and useful. It’s not every day that so much pharmacy happens in a rare disease state (they’re not called orphan drugs for nothing), but 2019-2020 were hot beds of action! And I’m just too pharmacy nerdy not to share my excitement.

Even if you don’t end up practicing in a setting where these patients come across your radar, tease out some pearls about medication classes or specific therapies that you can log away for later. You just never know what you might be doing in 5 years, trust me :)