Medication Safety Strategies for Pharmacists

Steph’s Note: This week, we’re going to discuss several inter-related topics near and dear to my heart. For anyone who knows me or has read my previous post on how to stay a strong pharmacist, you know that I’m a fan of keeping in mind that each and every patient is someone’s family member. So we absolutely should feel obligated to do our very best for each person we care for every day.

But…what happens when something goes wrong, and we make a mistake? How do we prevent this from happening again, or could we have avoided it altogether?

We’re pharmacists (or pharmacists-to-be) here. We’re type A, OCD (or CDO, to put it in alphabetical order as my co-resident once pointed out), detail-oriented perfectionists. It’s what we’re literally trained to be: eagle-eyes. And we hold ourselves to extremely high standards because it’s our job to see not only the trees in the forest but also the itty bitty beetles on the tree trunks.

So it’s pretty devastating when we make mistakes. (And trust me, if you are so lucky to be able to say that you haven’t made a mistake yet, don’t hold your breath. We’re all human, and I can pretty much guarantee you will make an error at some point.)

Now I’m not saying you’re necessarily going to majorly harm someone. This error could be something as simple as verifying an acetaminophen order with the incorrect dosage form. But because you’re a pharmacist, it’s going to be devastating nonetheless - because it’s GOING TO EAT AT YOU.

What if it wasn’t acetaminophen… What if the delay in the nurse being able to pull the med from the automated dispensing cabinet caused the patient discomfort from post-op pain or harm from a high fever… What if you verified the order with a tablet form but the patient was NPO without any enteral access, so they couldn’t be administered the pill? Did you verify any of the other orders in the set incorrectly, because if you did that with acetaminophen, did you do it with the heparin…

How it feels when you realize you’ve made one error and you’re wondering what else you may have done… BREATHE! (Image)

Aw crap, now you have to go review ALL of that patient’s orders again!!

Been there.

In fact, let me tell you about one of my early career medication errors so that the scenario is set. It was over a decade ago, and I was a PGY1 resident. I was dosing vancomycin for one of my patients, who happened to be morbidly obese, and I used the algorithm-based vancomycin calculator pre-built by my hospital. (I hadn’t done the actual vancomycin equations since my kinetics class in P2 year, and I couldn’t begin to tell you what they were at that point.) Without too much thought, I plugged in his weight and CrCl as calculated by the charting system, got back a dose, and rolled with that. Fast forward 3 days, when I checked a trough. It was 55 mcg/mL.

OUCH.

Now y’all tl;dr folks know I love talking about vancomycin dosing… Have you ever wondered why I’m willing to write PAGES about this medication?

You guessed it - that very trough.

Even though the patient was totally ok - his creatinine never budged, believe it or not - my confidence was totally wrecked. And from then on, I resolved that calculators would only be aids rather than crutches. So I dove back into the equations for vancomycin and re-learned what kinds of factors would influence how I determined doses for patients. But it took a total slap in the face and thinking that I could potentially have chronically injured this patient’s kidneys to slow down and THINK.

You know what else I did? I went back to the residents’ office, and I shared my failure with my colleagues. No one stabbed me through the heart with a giant sword. I’m still a pharmacist. And we were all a little (read: a LOT) more careful about vancomycin dosing in obese patients because we learned from my mistake. So in reality, it ended up being a solid lesson learned.

So what qualifies as a medication error, and how do we prevent these? How do we approach them when they do happen?

What is a Medication Error?

According to the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC-MERP), "A medication error is any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use.“

In simpler terms, a medication error is a PREVENTABLE occurrence related to a patient’s medication, WHETHER OR NOT harm ensues.

How often do medication or medical errors occur?

This is actually a really tough question to answer. Per the incendiary 1999 Institute of Medicine’s To Err is Human report, preventable medical errors caused anywhere between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths in the United States - every year. (You may have heard the oft-cited analogy: the number of people who unnecessarily die in hospitals is on the order of a jumbo jet crashing every day.) Some estimates are up to almost half of a million people every year! This estimate would make unnecessary medical deaths the 3rd leading cause of death in the US, only after cardiac disease and cancer.

DOUBLE OUCH. (No wonder people distrust the medical system with these kinds of numbers floating around!)

Health care is frequently compared to the aviation industry in terms of error prevention, and the constant question is why airline industries have been able to achieve such minimal error/injury rates while health care is still (apparently) out harming people in an egregiously common fashion. But is this truly the case? Are hospitals and health care really doing such a shoddy job?

Welllll…it’s still hard to tell, but a more recent study published in 2020 out of Yale suggests the earlier reports grossly overestimate the unnecessary death rates. These investigators conducted a meta analysis of 8 studies and concluded that there are about 22,000 preventable deaths in the US each year with only just over 7,000 of those being in patients who have a life expectancy of greater than 3 months.

Phew, breathe. That’s WAY less (I mean, still a lot - still too many - especially if one of those is your family member…but still, way less). But can we believe it?

It should be noted that this 2020 study included European and Canadian reports in the meta analysis and extrapolated the numbers to the US. Practice could certainly be different in those regions with varying access to treatments and different protocols. On the other hand, since this 2020 meta analysis only included studies published after 2007, perhaps the influence of the 1999 IOM report had taken effect through increased oversight and a tightening of the proverbial belt. Basically, maybe the combination of an incensed public and a shocked and scared profession created true change, such that the error and death rates have actually drastically decreased in the last decade or so.

There’s also the problems of error reporting and qualification. With regards to the former, it should be acknowledged that error reporting is not 100% at institutions. It is usually voluntary and dependent on an involved staff member feeling comfortable bringing forth the issue AND having the time to complete the report. So there’s always a caveat as far as any reported number having a wide confidence interval. Then there’s the latter issue of qualification. It’s important to be able to categorize errors to then investigate and quantify them. More on this in a bit, but we have to be able to talk apples to apples when distilling error reports down to common, addressable issues. On that note…

The 1999 IOM report wasn’t groundbreaking just because of the reported terrible numbers of unnecessary deaths. It was also because it discussed the concept of systematic failure rather than individual error. So perhaps the health care system failed its employee and its patient rather than an employee carrying all the blame for patient harm.

This is a complicated and STILL hotly-debated topic. At what point does system culpability yield to individual negligence?

If you haven’t already, take a look at this oh-too-recent case of a Tennessee nurse, whose automated dispensing cabinet override led to an accidental fatal administration of vecuronium instead of the prescribed Versed (midazolam). She described a situation in which she searched the cabinet system by “v” and went through several system flags. She also described that the health system had had some cabinet technical issues, although they had been resolved by the time she made her error. She admitted her error and took responsibility for the harm she caused.

After undergoing trial, she was convicted in March 2022 of criminally negligent homicide, setting an important legal precedent as one of the rare cases of a criminal conviction for a medical error.

Alright, virtual show of hands…just for kicks. No judgment zone here, not saying right or wrong for any of this, just want you to stop and consider. How many of you have been frustrated at the number of screens it takes to remove a medication from the unit cabinet? How many of you have personally used the override function on an automated cabinet because you could get to the medication you wanted more quickly than searching through the appropriate channels? (Ever needed to stock up on RSI and pain meds in anticipation of the arriving ER trauma patient, and because the patient isn’t yet registered in the system, you had to remove the medications on override? What about when you exhausted your code cart of epinephrine during an extended cardiac arrest case?) When verifying orders, how many of you have mindlessly clicked through the 1000th (seemingly useless) DUR or order verification flag? How many of you have seen other providers click through these?

What if something happened to YOUR patient? Could you now face time in prison for your mistake? And at what point is it your full responsibility versus a product of the health care system’s design - or some combination of these?

Are there too many warnings screaming at you to be able to weed out the truly useful ones? Were those two similar medications stored too close to each other? Did the pharmacy order a formulation that looks too much like another drug to be safe? Were you exhausted from being called in to work too many shifts in a row because COVID has made everyone short staffed?

See how it took multiple failure points in this patient’s admission for the harm to occur? Who holds the blame here, or is it a systematic failure? Or some combination?

You can see why assigning culpability is a very real - and convoluted - issue. Not to mention the implications for the future of error reporting if criminal charges are now on the table.

Which brings us back to the concept of systematic failure versus individual errors. Have you ever heard of the Swiss cheese model of medication errors? This is the idea that there’s almost always more than one point of failure leading up to an error, rather than one single failure point. Check out the Swiss cheese example to the right.

How can you reframe every medication error you encounter using the Swiss cheese model? Have you dug fully into each error’s story? In this vein, let’s move on to discussing the process for identifying, investigating, and preventing medication errors.

Medication Error Reporting

Remember how there are reports of anywhere between 22,000 and almost 500,000 deaths due to medical errors in the US every year? How can we have such disparate numbers?

Well, one piece of the puzzle has to be how the errors are reported. We need to have a standardized language for qualifying errors so that we as an industry are talking apples to apples. Luckily, NCC-MERP took care of this for us with their medication error definitions and categories (A-I):

Very much worth the read! (And I almost never read non-fiction voluntarily…unless it’s a journal article.)

One major accrediting body for health care institutions, The Joint Commission, encourages the use of a centralized, easily accessible reporting system for errors. Most institutions have adopted the above NCC-MERP error categories as part of this process, and although each institution’s reporting system may be different, they all usually ask for some form of critical assessment by the reporter.

Even though error reporting is voluntary, it should be highly encouraged and ideally non-punitive (unless the mistake is grossly negligent or repetitive in nature). Taking a “no harm, no foul” approach to errors doesn’t breed any quality improvement or preventative actions, whereas promoting a non-punitive culture of safety helps to identify potential failure points before the Swiss cheese allows something to fall through the cracks.

Hmm, what’s this “culture of safety”?

In the words of John Nance from his very interesting book Why Hospitals Should Fly, “Perfect safety…doesn’t mean eliminating all mistakes. It means structuring a system that expects and safely deals with mistakes… Dealing with failures effectively is the essence of a high-reliability organization.”

How do we do that? How do we achieve this culture of safety? Here are some major components:

Promote a “blame-free” environment

Who would actually report errors if they’re going to be punished for it?

Identify high risk medications

Use the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP)’s lists for high alert medications and Sound Alike Look Alike Drugs (SALAD).

Promote teamwork and collaboration

This quality improvement work is often spearheaded by a medication safety specialist, a job for which pharmacists are ideally suited!

Institute programs and procedures as safeguards

More on this, un momento.

Educate personnel

Every staff member of an institution should be trained on what an error is and how to report them - even near misses!

Involve patients

Some health care systems incorporate patients and/or family members on their advisory boards to ensure well-roundedness for actions and goals.

TALK!

This doesn’t just refer to pharmacists talking to each other or even pharmacists discussing errors with providers and nurses. This also encompasses the idea that ANYONE should feel comfortable speaking up in ANY environment if they feel there’s potential for an error.

Have you ever heard of Christopher Duntsch and how the OR staff tried - unsuccessfully - to speak up about his surgical practices? If you haven’t and you want to learn about how far health care has come in even a few short years, check out the Dr. Death podcast here. Talk about Swiss cheese! (But also individual responsibility…)

Now let’s delve a little more into this idea of instituting safeguards…

Strategies for Preventing Medication Errors and Quality Improvement

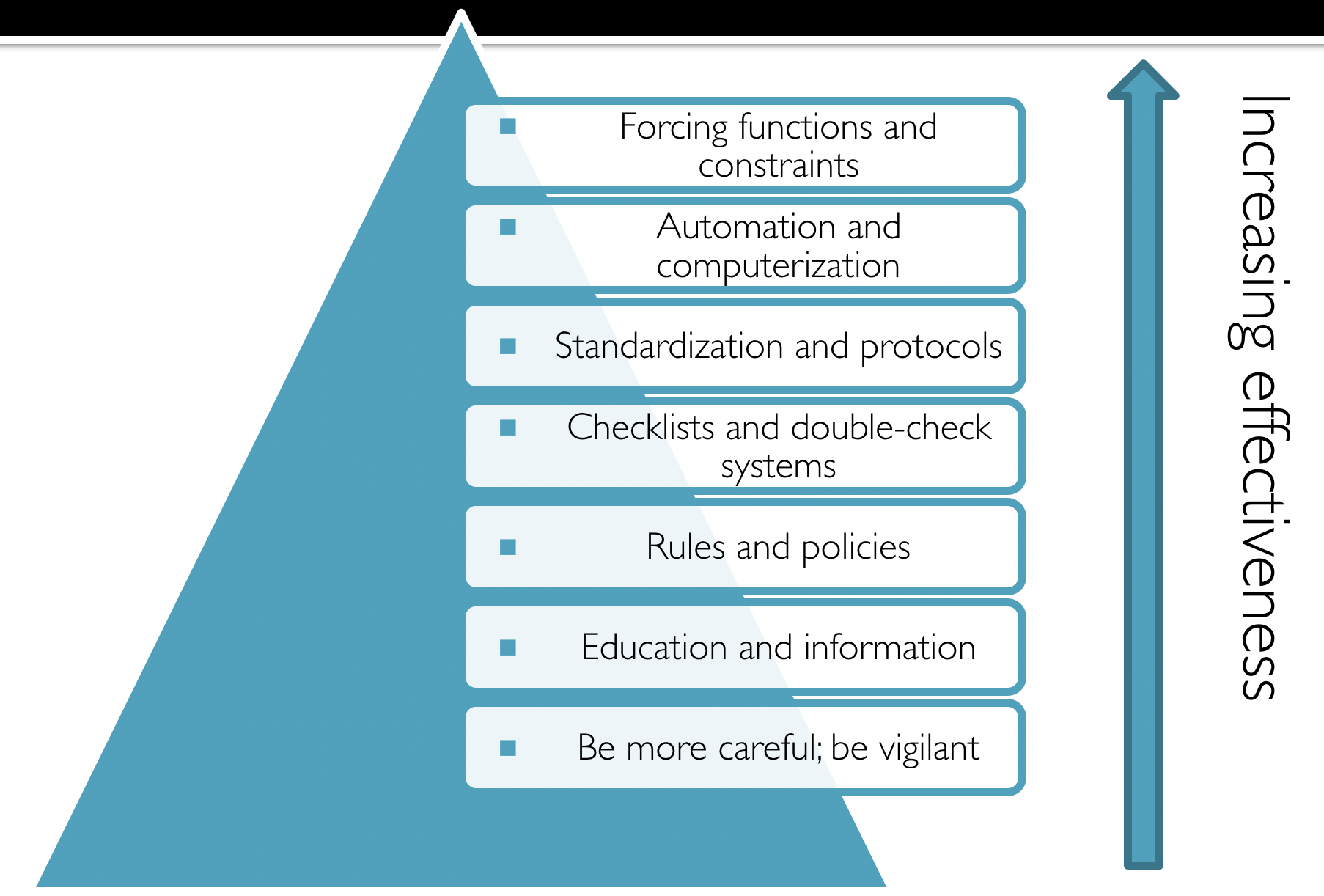

There is a wide variety of safeguarding strategies that institutions can implement in order to prevent medication errors. Each of these has its place, but they’re not exactly all created equally in terms of how effective they are for actually preventing an error. For example, a manager can tell an employee to be more careful. Don’t miss things. But really, when the crap hits the fan and it’s crazy busy, how likely is it that the manager’s verbal caution is going to stop an error? For even the most well-intentioned employee, crap happens, and reminders don’t inherently carry any action.

Let’s compare this with a forcing function or constraint. If the computer system has a hard stop for any order of vancomycin over 2500 mg at a time, that certainly is going to be more effective for preventing extra zeros or larger doses than just telling someone to be sure to type doses correctly. (This is the idea behind guardrails on infusion rates - the libraries are built to allow for specific ranges of infusion rates per each drug’s recommendations. You can not override these.)

Safeguarding procedures to protect against medication errors.

Of course, there has to be a balance of when to use these harder stop forcing functions. Implementing too many of these can be counter productive and may even lead to delays in therapy (and patient harm from LACK of therapy). So just because forcing functions are technically more effective for preventing errors doesn’t mean that we should just enact forcing functions on every path.

Imagine trying to do your pharmacist job without any leeway whatsoever for clinical judgment. That’s not necessarily great patient care either. So again, there needs to be some give and take here because not every patient fits the guideline mold.

Check out this figure to the left for a summary of safeguards.

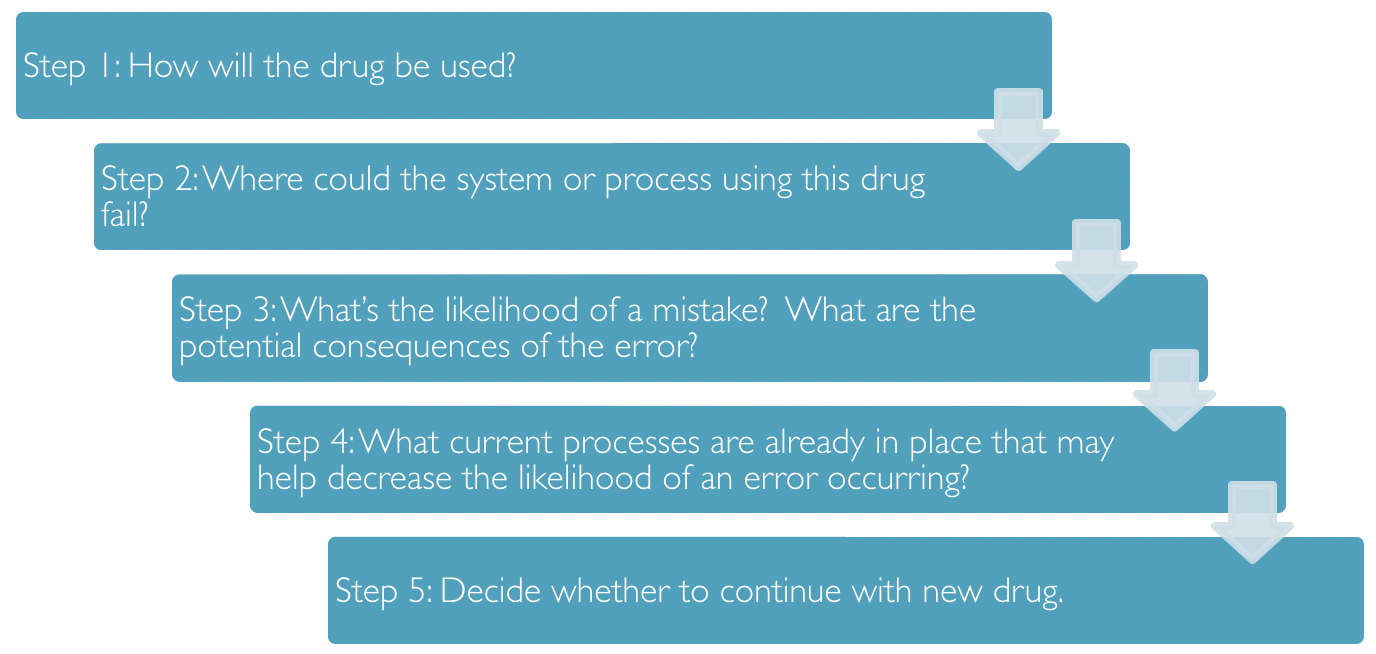

Sample FMEA for medication error prevention.

In order to determine whether a proposed prevention strategy is sufficient and appropriate, many institutions will conduct a FMEA, or Failure Mode and Effects Analysis. The key here is that this process is to be used BEFORE an error occurs. Another important piece is that these analyses should be multi-disciplinary so as to avoid tunnel vision.

(Remember, we pharmacists are often reeeeeally good at seeing the beetles on the trees, but sometimes we’re not great at evaluating the forests. So it helps to have some additional brains at the table who are able to assess the 20,000 foot view or how the ripples will spread and affect others. Even when the fix for a system issue seems SO OBVIOUS to you as a front-line staff member, it’s possible that your obvious fix will wreck someone else’s work flow. Better to check as much up front as you can rather than institute a change, get backlash, and have to start from scratch again!)

On this note, this continuous process of making things better is known as quality improvement. And it’s kind of a big deal in health care - because obviously we aren’t perfect, no matter how perfect we try to be as a profession. So we have to figure out how to BE BETTER.

I’ve been waiting for a perfect moment to incorporate 21 Jump Street into tl;dr, and boom, here it is. (Image)

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) uses a process called the PDSA cycle. This stands for Plan, Do, Study, Act. For this strategy, you plan your change, make your change, observe and learn from the consequences of the change, and determine what modifications may still be needed to produce the desired outcome. Then you act on those modifications, which starts the PDSA cycle again. Which is why it is called continuous quality improvement. (You can’t just implement a new protocol and drop the project, mic drop style. You have to follow up to make sure it has the desired effect for all involved parties.)

A second quality improvement process acronym is DMAIC. This stands for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. It’s easy to see this acronym results in the same continuous improvement cycle as PDSA. (There are many more acronyms available for defining a quality improvement cycle, but they all encompass the same ideas as PDSA and DMAIC). Long story short, you can’t just make the change and peace out…you have to follow it through to ensure that it caused the effect you desired - and didn’t cause any undesired effects either!

Even with all of these safeguards and prevention strategies, errors still make it through the Swiss cheese. Once an error has occurred and is reported to the institution’s system, how should it be assessed?

Strategies for Evaluating Medication Errors

There are several processes for accomplishing this, and every system seems to dub these by their own names. Most of the time, you’ll hear that a root cause analysis (RCA) is involved. So what is an RCA?

An RCA begins after an event has occurred and works backwards to elucidate possible causes. (Recall that an FMEA is conducted before implementation of a process, whereas RCA is done after implementation and an event has occurred.) The key to a solid RCA is asking why. Many, many times. You and your team essentially continue to ask why until you’ve broken down the situation to its bare bones and can’t go backwards with why anymore.

Although you of course can do a solo RCA, it is usually more effective if you have other brains on the task with you. (Teamwork makes the dream work, right?) Sometimes you don’t have the full history of a protocol that was implemented or why things were designed the way they were, so it can make answering why increasingly difficult. Get those other brains at the table!

Executing a solid RCA also requires openness and honesty with your team. This is not the time to gloss over failure points for yourself or for your department to try to save face. This is the time to really dig into what are all the possible failure points. (And this is why it’s so important to keep in mind that you are doing this RCA to evaluate for system errors rather than just individual mistakes.)

Check out this simplified version of a sample RCA (sorry, had to simplify quite a bit here because these can often take up entire whiteboards!):

Problem: Bupropion was dispensed instead of buspirone.

Why? A bupropion unit dose was mistakenly returned to the buspirone medication bin.

Why? The bar code scanner step was bypassed when completing medication returns.

Why? The bar code scanner has been malfunctioning in recent weeks and dying prematurely every shift.

Why? The charging base keeps getting moved to different locations in the pharmacy, and nobody ever knows where to find it.

Why? There’s no electrical outlet to plug in the charging base next to the medication bins where the bar code scanner is used the most.

Why? No one’s ever asked for an outlet there…

Well, hot dog, lookee there! We have an addressable issue! We can ask the engineering department about installing an electrical outlet next to the medication bins so that the charging base can live in a single, more convenient location, helping to ensure it is readily available for use during medication returns!

Is this the only possible root cause of the error? No, of course not. You can take the why’s in multiple directions, and you should. Because fixing the electrical outlet issue may address one important hole in the Swiss cheese, but I’d bet my bottom dollar there are others. The RCA can help to elucidate these issues, so follow the yellow brick road of RCA.

(Image)

RCAs are an essential component of a larger quality improvement strategy called the A3 process. (I always learned it was called this because the process summary is printed on A3 paper rather than letter-sized paper. Not a very exciting nomenclature, but it works, even if it is old fashioned… why print anything anymore?? #saveatreeorthree).

I have to admit - I LOVE a good A3 process. It’s like the quality improvement engines fire up, there are multiple disciplines at the table ready to FIX a problem, and it just makes my heart so happy! Nerd alert, I know. But when you have the right people at the table to flesh one of these out and make a change for the better, man, it is just b-e-a-uuuuutiful.

A3 love story aside. Here are the steps to conducting an A3 quality improvement project:

Define the problem or need. You have to really nail down the issue is here. It’s kind of like the mission statement for your A3 project, so it should be targeted, detailed, and accurate. For example, your issue shouldn’t just be, “Medication histories are useless.” You really need to be specific - something more like, “Inaccurate and incomplete admission medication histories contribute to inpatient and discharge medication errors, leading to increased readmission rates at X hospital.” You can also include any supporting data you may have from other quality projects with additional statements, such as, “An estimated 75% of patients at X hospital have at least one error on their admission medication list, with approximately 30% of those having the potential to cause significant harm to patients.” Whatever, the point is to be specific about the problem or process gap.

Map the current process. Before you go about trying to change a process, you really need to FULLY understand it in its current state. This doesn’t just mean you understand you or your department’s role in the process. It means you understand it from all angles! You will likely have to reach out to other disciplines and bring them to the table to hear their versions of the involved process and how their workflows are built. Have fun with Microsoft Visio or Powerpoint. Really go wild here and flesh out every step, even it it seems like minutia.

When you finish mapping out the current process, make notes of where the “storm clouds” are. Aka, what are the issues with this process and note them on the map.

Complete a root cause analysis for each storm cloud. Yep, you read that right. You’re not just doing one RCA… You’re doing an RCA for every failure point in the process. You need to really drive those whys down to the bones. Because once you have the root causes for each storm cloud problem, you will…

Develop countermeasures for the failure points. Again, this is where team work makes the dream work. You may not personally know how to fix each storm cloud failure point. But as you seek input from invested parties who work in different areas, you will collect proposals that come from the proverbial horses’ mouths. And you will be better equipped to devise solutions. Once you have some ideas for how to fix the failure points, then you can…

Map the ideal process. Use your countermeasures to map out what you would like the process to look like. Dream big here, nothing is too out of reach. You want this to be a reflection of, “If I had all the resources and could do anything to fix these issues, what would this process look like?” Then, once you know where you are with the current process map and the ideal state map, you can begin to…

Develop strategies to implement the ideal state. Ok, so of course you would love to have 5 pharmacists and 15 technicians dedicated to doing medication histories in the ER every day to catch every admission. (Who wouldn’t???) But since that’s unlikely, what can you reasonably justify in a request for FTEs?

Maybe you start by asking for 1 pharmacist for oversight and 2 technician FTEs for the ER. Maybe you design a training program for all current pharmacy staff regarding obtaining improved medication histories. Maybe it’s that you realign staff you currently have to create a medication history team, and maybe these responsibilities can be combined with some other ones to improve bang for your buck. Maybe you develop a pharmacy student internship devoted to medication histories and partner with the local college of pharmacy.

This is basically the step of figuring out ways to bridge the gap between current and ideal processes, so GET CREATIVE. Talk to others, bounce ideas around. Then start working on the nitty gritty details for your most promising plans.

Don’t forget to follow up. How will you measure the success of your new medication history program? What metrics will you use, and how often will you pull them? How will you present them (and to whom)? Devise a plan to monitor how your new process is working and then follow through.

A sample A3 process improvement report. Wish I could find one of my old ones to upload here, but alas… (Image)

If all this talk about quality and process improvement hasn’t totally snoozed you, you may have noticed that an A3 is really just a more detailed version of PDSA. Someone at Toyota outlined more of the PDSA steps for all of us to apply more fully in the A3 format, but the general scheme is the same… So don’t let all the acronyms overwhelm you. I just want you to be aware of some of the Lean/Six Sigma lingo, so if you hear these terms thrown around in a meeting, you’ll have a leg up! (See what I did there with Lean and Six Sigma? Threw some more quality improvement lingo at you!)

Alright, I think this is enough about errors and process improvement for now.

The tl;dr of Medication Error Prevention and Assessment for Pharmacists

There’s a lot to swallow here, but I want to summarize with these thoughts. First, you’re a human and not a machine (no matter what your ex or your boss say), and you will make a mistake at some point in your career. Try to prevent it, of course, but when it happens, learn from it. And help others learn from it too.

Next, promote a culture of safety. Figure out if there’s something that needs to change systematically in order to stop it from happening again. And then work to make that change with the appropriate people at the table. Plug as many holes in the Swiss cheese as you can.

“Be a hero. Don’t do the work around. Quality is everyone’s job.”

And then once you’ve made your process changes, don’t forget the key last step of quality improvement… CONTINUOUS assessment. What works today may not be best forever, so don’t get stuck in a rut!