How to Treat Urinary Tract Infections

We’re real people! And we met in real life! And we cheese for the selfies!

Steph’s Note: We at tl;dr love us some antibiotics. If you don’t already, honestly it’s best to get on this train sooner rather than later...we’ll help you.

Dev Chatterji, PharmD, BCPS is back with us. Dr. Chatterji is the PGY1 Residency Director at INOVA Fairfax in northern Virginia, and he is also an internal medicine and infectious diseases guru. From his original blog contributions about obtaining and succeeding as a resident, he’s well known to our crew. (And fun fact, we actually got to meet in person last week. Yes, of course we totally selfie’d and sent it to Brandon for the small pharmacy world moment.) Anyways, let’s get started with UTIs!

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common bacterial infections for which we utilize antibiotics. It’s sort of a ‘bread and butter’ disease state in the ID world, and since UTIs are encountered in both the inpatient and outpatient setting, it’s a worthwhile topic to have a solid handle on.

Close. So close. #blesshisheart (Image)

Since most pharmacists and pharmacy students alike love them some guidelines, I won’t deprive you…here, here, and here are some important guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) surrounding the management of urinary tract infections, including a new update on asymptomatic bacteriuria from within the past year.

Pharmacists, when new guidelines are published.

UTI Pathophysiology

A UTI occurs when there are microorganisms in the urinary tract and can present as a variety of syndromes—cystitis, pyelonephritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, and prostatitis.

Let’s take a quick moment to differentiate cystitis vs UTI. They might sound like the same thing (and often, they are). But not always. Cystitis is inflammation of the bladder. It COULD be caused by an infection. But it might also be due to something else. A UTI almost always involves cystitis, but as the name suggests (urinary tract INFECTION), there is an infectious presence.

Likewise, we should differentiate cystitis vs pyelonephritis. The difference is how far up the ureter the inflammation/infection has traveled. If the infection has gone all the way up to the kidney, you’re dealing with pyelonephritis.

There are actually several different ways UTIs are classified, first by either lower or upper UTI and then by either being complicated or uncomplicated.

Lower UTIs

A lower UTI occurs when the infection occurs from the bladder to the urethra—this is referred to as cystitis. Cystitis is more prevalent in women than in men. Approximately 60% of women will develop a UTI in their lifetime! This is mostly attributed to anatomy — namely females having a shorter urethra with close proximity to the perirectal area, which allows bacterial organisms to enter into the urinary tract more easily.

Upper UTIs

An upper UTI occurs when the infection involves the kidneys—referred to as pyelonephritis. In this type of UTI, bacteria can either ascend to the kidneys by the ureters (more common) or descend to the kidneys via hematogenous seeding (less common).

(Image)

Following location of the infection, the other terminology we use to distinguish UTIs is determining whether it is a complicated or uncomplicated UTI.

Uncomplicated UTIs

The key thing here to remember is that there is no systemic involvement

Nothing above the bladder or kidneys

No obstruction or signs of intrinsic disease

Typically occurs in healthy, non-pregnant females 15-45 years of age

Complicated UTIs

Women with the following:

Pregnant with cystitis

Indwelling catheters, stents, or nephrostomy tubes

Renal calculi

History of renal transplantation

Functional or anatomic abnormality

Recent urinary tract instrumentation

Diabetes

Immunosuppression

Renal failure

Men

It is not normal for a man to have a UTI, so the infection is automatically considered a complicated UTI even without the risk factors named above for women. To emphasize that point, if you have a male patient with a UTI, it is a complicated UTI.

Children

Kidney involvement

Suggestive of a pyelonephritis (and pyelonephritis is automatically a subset of a complicated UTI)

Urinary Tract Infection Risk Factors

As mentioned above, UTIs are the most common bacterial infection in women, but there are certain predisposing risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing a UTI. Infection is relatively uncommon in men, but risk increases after the age of 65. Listed below are some of the predisposing risk factors for both women and men:

Females

Diabetes

Pregnancy

Antibiotic use

Sexual activity

Diaphragms or spermicides

Foley catheter

Fecal incontinence

Males

Foley catheter

Outlet obstruction

Kidney stones

Homosexual activity

Fecal incontinence

Sexual abstinence

UTI Microbiology

UTIs are primarily caused by Gram-negative bacteria, but there are Gram-positive bacteria that may be implicated in certain circumstances. Most uncomplicated UTIs are caused by a single organism. While polymicrobial UTIs are possible, these are more common in patients with complicated or recurrent infections.

Most of you all likely know that the most common pathogen for UTIs is E. coli (>80% of cases). Other common organisms include: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus species, Proteus mirabilis, and Enterobacter species.

The table below is a good summary of common bacteria associated with UTIs based on type of UTI. This information primarily comes from one of the most trusted sources in the ID world - Mandell’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases.

Urinary Tract Infection Diagnosis

Although we try not to get too caught up in diagnosis from the pharmacy standpoint, there are some key aspects of diagnosing a UTI that you should be familiar with.

Patients with cystitis (lower UTI) can generally present with the following signs/symptoms: dysuria, urgency, frequency, nocturia, gross hematuria, or suprapubic heaviness.

(Image)

Patients with pyelonephritis (upper UTI) generally present with flank pain, fever, vomiting, and malaise. A specific type of back pain (technically called: costoverteberal angle tenderness) is also often present.

In addition to clinical presentation, the next aspects of diagnosis are the urine studies since observing bacteria in the urine specimen (bacteriuria) is key to diagnosing UTIs.

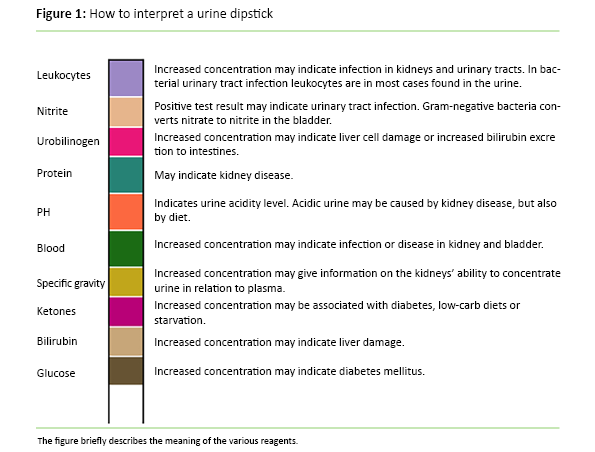

Urinalysis (UA)

This is usually done via the common dipstick test we all learned about in school. The figure below briefly explains how to interpret the different components. The two most important components are Nitrite and Leukocyte esterase. If you see these two in combination, it’s a HUGE indicator of a true infection:

Nitrite: reported as positive or negative. A nitrite positive test occurs when bacteria that reduce nitrate in the urine are present. Examples of these bacteria include: E. coli, Proteus species, and Klebsiella species. Caveat: some bacteria do not produce nitrate, so the UA being nitrate negative doesn’t outright rule out infection.

Leukocyte esterase: Indicates the presence of white blood cells (detects a WBC count greater than 10 x 10^3 cells/mm^3)

(Image)

Urine Culture

As you can imagine, a urine culture would be the most reliable method for confirming diagnosis. A urine culture is usually not necessary for managing uncomplicated cystitis. However, a urine culture should be obtained for patients with suspected pyelonephritis and any type of complicated UTI. In these situations the culture results help determine and optimize a definitive antibiotic regimen.

Most cases of true infection have a bacterial count of greater than 100,000 bacteria/mL. So when cultures return with bacterial cell counts of 10,000 bacteria (or CFUs = colony forming units)/mL, usually these are not considered pathogenic. It gets a little tougher to interpret when the counts are 50,000 or 80,000… especially in certain patient populations.

UTI Treatment

General Considerations

First, some general guidelines. Use the following framework to steer your treatment approach with urinary tract infections.

Classify whether it is a lower UTI (cystitis) or upper UTI (pyelonephritis)

Determine whether the UTI is complicated or uncomplicated

Consider likely pathogens and review the patient’s history (very important!!)

Be aware of local susceptibility patterns (i.e., your institution’s antibiogram) as this can assist in selecting the most appropriate empiric therapy

Antibiotic Selection Considerations

Similarly, you’ll need a framework for picking the best antibiotic for your patient. Make sure to keep in mind the following key factors.

What pathogens does your antibiotic cover?

How well does the antibiotic concentrate in the urinary system?

One way to assess this (and by no means is this the end all/be all way) is to look in the PK/PD section of the drug monograph (either in a reference such as Micromedex or LexiComp or the package insert) and note the percentage of urinary excretion. If, for example, you note the following wording, “primarily urinary excretion, 80% unchanged”, then you can rest assured that the drug will have good urinary concentrations.

Adverse medication effects and drug interactions (i.e., may want to avoid trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as your choice for a UTI if the patient is also on warfarin)

Renal function adjustments

Concomitant disease states

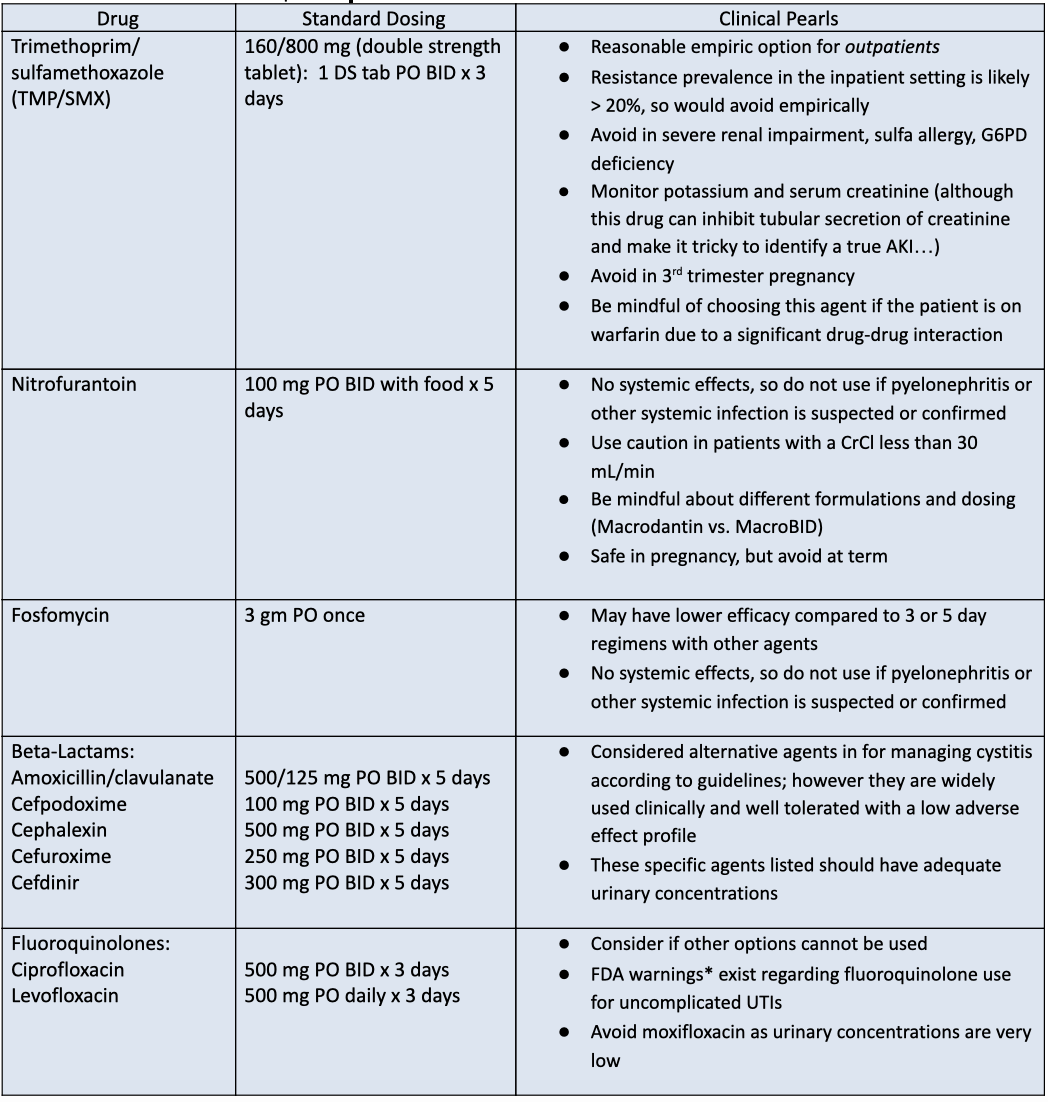

Treatment of Uncomplicated Cystitis

Common Antibiotic Regimens for Uncomplicated UTIs

3-day courses of therapy

TMP/SMX (Bactrim)

Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin

5-day courses of therapy

Nitrofurantoin

Beta-lactams

Amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate

Cephalexin

Cefuroxime

Cefpodoxime

Cefdinir

Single dose therapy

Fosfomycin

*FDA warnings about fluoroquinolones

Treatment of Complicated UTIs

Complicated UTIs generally occur in patients with some underlying condition that puts them at risk of increased treatment failure (see above list). Here are some quick tidbits about select types of complicated cystitis. In general, treatment options are the same, with the main difference being a longer duration of therapy for complicated cystitis.

How to Treat UTIs in Pregnancy

Pregnant women with UTIs are automatically considered complicated as these patients are at much higher risk of developing pyelonephritis if not properly treated. Pregnant patients should be screened and treated even if they’re asymptomatic.

Duration of therapy: 7 days

Agents that are good options:

Beta lactams

Amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefuroxime, and cefpodoxime are the ‘broader’ oral beta lactams that are likely effective

If susceptibilities are known, agents such as cephalexin or amoxicillin are fine as well

Nitrofurantoin

Generally safe, but avoid at term (~37 weeks and onward) due to concern for hemolytic anemia in the infant

Fosfomycin

Safe and effective option in pregnancy

Single dose therapy (but can require prior authorization)

TMP/SMX

A reasonable and safe choice in the 1st and 2nd trimesters but should be avoided thereafter

If used, ensure that your patient is taking folic acid

Agents to avoid in pregnancy:

Tetracyclines

Not that you’d generally go to these agents for a UTI anyway, but avoid especially in pregnant patients

Fluoroquinolones

‘the hits just keep on coming’ against these agents, don’t they?

Sulfonamides (during the 3rd trimester and beyond)

How to Treat UTIs in Men

Treatment options are similar to uncomplicated cystitis with the main difference being duration of treatment.

Aim for 7 days of treatment unless there is concern for pyelonephritis or prostatitis.

How to Treat Catheter-Associated UTIs (CAUTIs)

Treat in patients with signs/symptoms of a UTI and no other identified source of infection.

Diagnostic highlights:

Symptoms consistent with a UTI AND presence of ≥ 10^5 cfu/mL of at least one bacterial species (i.e., a positive culture)

Presence of pyuria and bacteriuria are NOT diagnostic and not indications for treatment in patients who lack symptoms of a UTI

Duration of therapy: 7 days (may consider extending to 10-14 days in patients with a delayed clinical response)

Agents that are good empiric options:

Inpatient, not severely ill

Ceftriaxone

Other beta-lactams based on risk factors and institution specific antibiograms

Cefepime

Piperacillin/tazobactam

Meropenem (if there is a history of multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens)

Inpatient, severely ill, including urosepsis (which isn’t really a recognized term anymore, but still)

Coverage to include Pseudomonas species

Cefepime

Piperacillin/tazobactam

Meropenem (if there is a history of multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens)

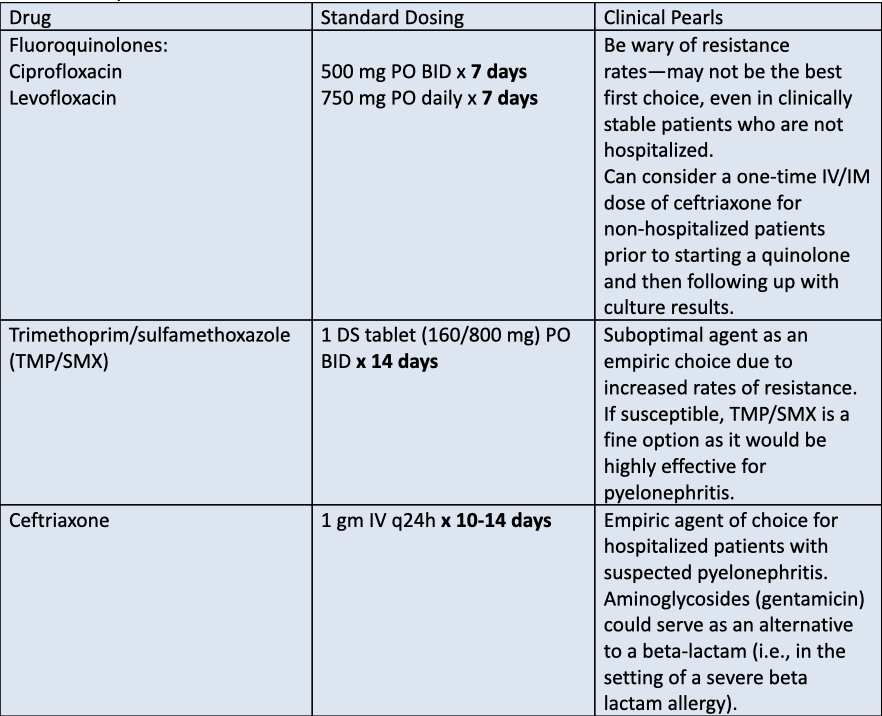

How to Treat Pyelonephritis

Patients presenting acute pyelonephritis (high fever, severe flank pain) are generally managed more aggressively than patients with cystitis.

Pyelonephritis can be managed in the outpatient setting with oral antibiotics that achieve high serum and urinary concentrations; however, severely ill patients with suspected pyelonephritis will likely be hospitalized for parenteral antibiotics. You will also typically see longer durations of therapy for acute pyelonephritis to ensure adequate penetration into tissues and to eradicate causative organisms.

Treatment options:

Interestingly, there is some movement towards shorter courses of antibiotics for pyelonephritis, even when blood cultures are positive. Check out this 2018 study to see if your patient would qualify based on study criteria.

Other UTI Considerations

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Patients with positive urine cultures who lack symptoms of a UTI have the diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Screening for and treating asymptomatic patients is generally NOT recommended.

Screening and treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria should only occur if it could lead to an adverse outcome (i.e., bacteremia, development of a symptomatic urinary tract infection). The two clinical situations that warrant treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria are:

Pregnancy

Urologic procedures where bleeding is likely to occur—such as transuretheral resection of the prostate (TURP)

Antibacterial Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections

It is of the utmost importance to be familiar with local susceptibility patterns for commonly associated organisms for UTIs—aka your local antibiograms. This data is really what drives empiric treatment options. Fluoroquinolones and TMP/SMX generally have at least 20-30% resistance in most areas of the United States, so they are probably not the best empiric options anymore despite what our guidelines tell us. This, along with far better tolerability, is probably why beta-lactam use has become so common in the real world setting.

What MDR bacteria look like. Ok, maybe not, but they are still a nightmare! (Image)

Medications that you may have to pull out of your armamentarium when you have patients with risk factors for MDR organisms:

Piperacillin/tazobactam

Cefepime

Meropenem or ertapenem

Ceftazadime/avibactam (Avycaz)

Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa)

Another medication that you may be able to consider for UTIs caused by MDR organisms is fosfomycin (if there is no suspicion for pyelonephritis or systemic infection).

It’s the same dose as for uncomplicated UTI, but the duration is extended in the case of resistant bugs. So it becomes 3 gm PO q48h x 3 doses.

UTI Prophylaxis

In patients with recurrent infections, recommended treatment options are as follows:

Non-pharmacological preventative strategies

Cranberry juice

Topical estrogen replacement in post-menopausal women

Antibiotic prophylaxis

In patients with more than 3 UTI episodes in a year, you can consider antibiotic prophylaxis. But remember this can also cause collateral damage since you are using chronic antibiotic therapy!

TMP/SMX: ½ of a SS tablet daily x 6 months

Nitrofurantoin: 50 mg PO daily x 6 months

For select patients with recurrent UTIs, self administration of a short course of therapy for 3-5 days at symptom onset may also be an option (if the provider trusts the patient and is willing to prescribe antibiotics).

tl;dr - UTI Treatment Considerations

DO NOT treat asymptomatic bacteriuria with the exception of pregnancy and select urological procedures

Be familiar with local susceptibility patterns to gauge your ‘best bet’ empiric choices

Fluoroquinolones— only use these agents when you have to

Pay attention to durations of therapy

We are sort of in a ‘less is more’ era these days so reserve longer courses of treatment only for patients who fail to clinically improve