Heart Failure Part 3: Pharmacotherapy

Courtney’s Note: Hi, tl;dr fam! Hopefully you’ve noticed we’ve been hard at work updating old, out-of-date articles. Lucky for us, most of them have only required minor tweaks thus far. This article, however, is giving “throw the whole thing away and start over” vibes. Alright, that might be a bit of an exaggeration, but it does need some serious re-work. And not because of the quality of the original article. Trust me when I say J. Nile Barnes (who also wrote parts I and II of this series!) did a fantastic job. It’s just that it’s been EIGHT YEARS since it was published, and the heart failure guidelines have changed significantly. I’ll do my best to retain as much of Dr. Barnes’ original content as possible, but know that a majority of this article will be new.

As an FYI, you can get all 3 posts in this series as one downloadable (and printer-friendly!) PDF. PDF currently under construction as this series is being updated!

Just a reminder where we have been and where we are going today:

Episode 1— Pathophysiology (especially hemodynamics)

Episode 2— Signs and symptoms (focusing on mechanism)

Episode 3— Return of the JEDI mechanisms, using the mechanisms as drug targets (you are here!)

Okay, now onto pharmacotherapy.

Heart Failure (HF) Drug Pharmacodynamics

Here’s something that didn’t change: The pharmacodynamics of HF drugs. Remember, pharmacodynamics is just a fancy word for describing what a drug does to the body.

Last time, we talked about signs and symptoms and discussed the Frank-Starling curve. Today, we are going to talk about the agents used in HF and how they affect this curve.

You might notice that the labels on the axis have changed since the last installment, but don’t worry. These are just different surrogate markers we can use for the same thing.

Stroke volume (SV) is related to cardiac output (CO) which is normalized to cardiac index (CI). Ventricular filling pressure is related to left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP). So, it doesn’t really matter which ones I pick.

Not even going to attempt to re-create this figure. Image

In the figure above, taken from Goodman and Gilman’s:

D = Diuretics

I = Inotropes

V = Vasodilators

The solid green line represents normal function, and the red line represents someone with severe HF. The two dashed lines represent improvement with drugs that we will discuss below.

If the red dot represents where the patient is in severe cold, wet failure, you can see that adding a diuretic alone simply moves the patient down the curve from cold and wet failure to cold and dry failure. Drying the patient a bit would decrease LVEDP with little effect on SV.

Just adding an inotrope would move that patient’s curve (and spot on the curve) from cold and wet to warm and wet failure by increasing CI (or SV).

Just adding a vasodilator would decrease afterload, which would allow for a greater SV and would drop vascular pressure. This would move the curve upward (improved SV) and the patient down the curve (relative decrease in pressure).

You can also see the effects of adding all three agents. These effects are what we are trying to achieve in acute heart failure syndromes. In chronic heart failure, we don’t have to be so aggressive, but we follow the same plans.

Heart Failure Staging and Classification

Before we get too far into the weeds of pharmacotherapy, it’s important to understand how HF is classified. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) have identified four stages of HF:

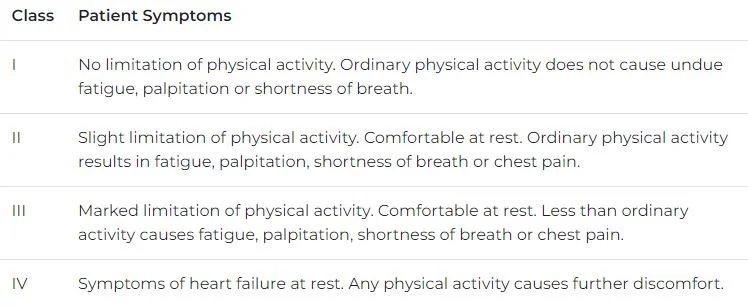

Patients diagnosed with stage C or D HF can be further classified by their functional status using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification system:

A patient’s ejection fraction (EF) can also help guide their treatment.

Does EF sound familiar? It should, because we talked about it in part I of this series. As a reminder, EF is a measure of how much blood the left ventricle (LV) pumps out with each contraction (and so it’s called the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)). It’s expressed as a percentage and is normally 55-70%.

When a patient has HF but the EF is normal (≥ 50%), we call it heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). When the EF is ≤ 40%, it’s called heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

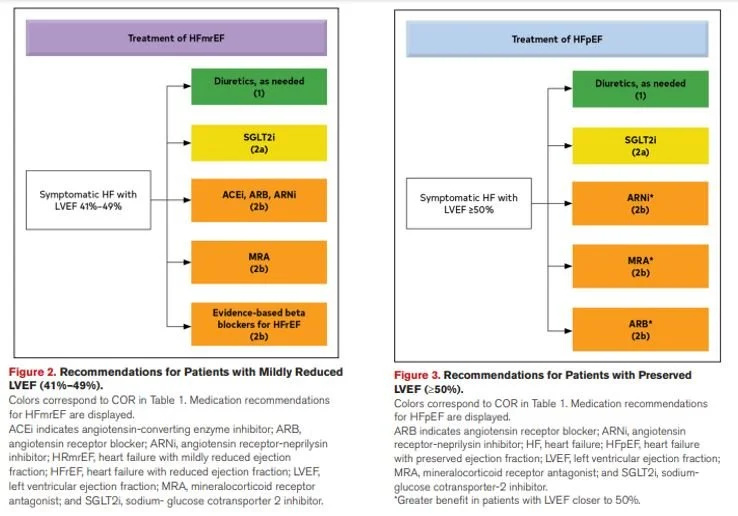

These classifications have been around for a long time, but the 2022 guidelines also address two newer categories: heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and heart failure with improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF). Patients whose EF falls between HFpEF and HFrEF (41-49%) are assigned HFmrEF, and those that have HFrEF but improve their EF to > 40% upon reassessment are considered to have HFimpEF.

Chronic Heart Failure Pharmacotherapy over the Years

Like I said in the intro, the HF guidelines have changed quite a bit in recent years. Because of this, your understanding of HF pharmacotherapy may be pretty different from the current guidelines depending on when you went to pharmacy school and whether or not you actually see HF in your practice.

I won’t spend much time on the old recommendations, but I think it’s important to touch on them to see how the guidelines have evolved. Since stage C represents the start of symptomatic HF, this is the one we’ll focus on. It’s also important to note that we’re talking about chronic HF treatment, NOT acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

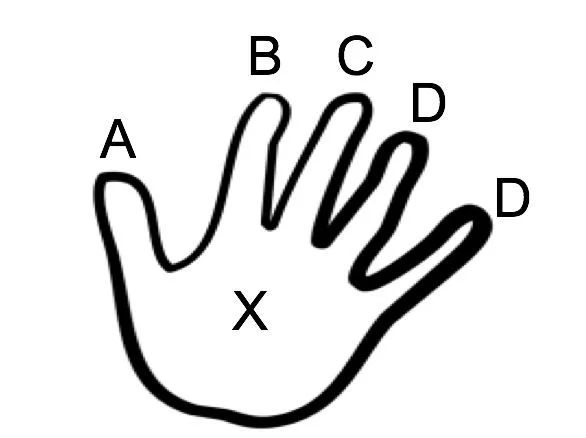

In the original article, Dr. Barnes (courtesy of Dr. Mark Granberry) gave us this HANDY (you’ll get that one in a minute) little memory device to remember the previously recommended treatment for chronic, stage C HFrEF:

Get it? HANDY? Hilarious, I know. Here’s how to decipher it:

A for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) OR angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

B for guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) beta-blocker (BB)

C for stage C patients

D for digoxin

D for diuretics

Hold in the palm of your hand for special patients:

Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi)— sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto®): NYHA class II-III, adequately controlled blood pressure (BP) on ACEi or ARB, no contraindications to ARB or sacubitril

Aldosterone antagonists: NYHA class II-IV, LVEF ≤ 35% with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, and K < 5 mEq/L

Hydralazine + isosorbide dinitrate (BiDil®): African American patients with NYHA class III-IV HF

Ivabradine: NYHA class II-III, on maximally tolerated BB and in normal sinus rhythm (NSR) with resting heart rate (HR) ≥ 70 BPM

This is a pretty great mnemonic device if you ask me. The good news? A lot of it still applies.

These recommendations reflect the 2013 HF guidelines, as well as the 2016 and 2017 focused updates.

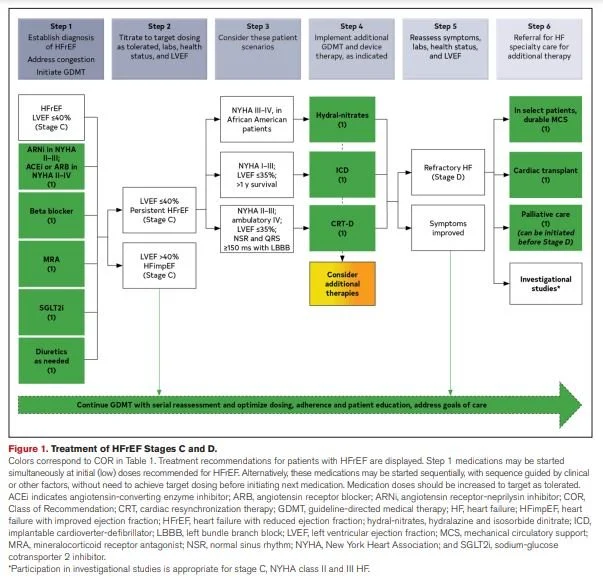

Alright. So that’s where we were, and here’s where we are now. Below is a screenshot of the updated recommendations for HF Stages C and D from the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure (and here’s a link to the executive summary because ain’t nobody got time to read all that):

As you can see, much of the backbone of therapy has remained the same: ACEi OR ARB, GDMT BB, and diuretics. BiDil® is still recommended as an add-on option for African American patients with NYHA class III-IV HF.

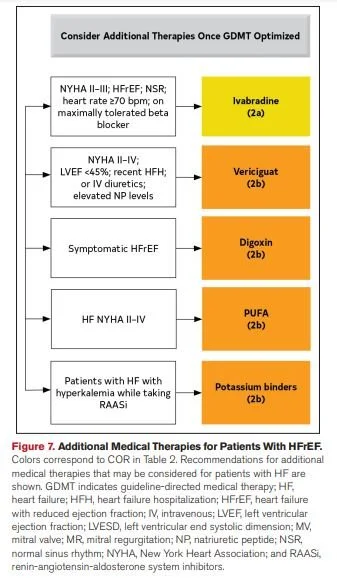

Here’s what changed: The ARNi (Entresto®) is now recommended as a first-line option on par with an ACEi or ARB. Aldosterone antagonists (AKA mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs)) are now part of the backbone of therapy. They were recommended for those with NYHA class II-IV HF in previous guidelines, too, but now have a special place in the treatment flowchart. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are now recommended for all patients with stage C HFrEF. And, finally, ivabradine and digoxin have fallen out of favor. They are still options for add-on therapy, but they are not highlighted in the 2022 update since there more effective and less toxic treatment options.

A Deeper Dive Into Heart Failure Treatment

Now that we’ve had our history lesson, let’s take a closer look at the current recommendations for chronic Stage C HFrEF.

The Backbone of Heart Failure Pharmacotherapy

ARNi OR ACEi OR ARB

ACEis and ARBs have long been considered a first-line treatment option in HF. The 1992 SOLVD Treatment study established enalapril as first-line therapy in preventing HF progression. Additional trials established this was a class effect for ACEis.

ARBs were evaluated as substitutes for ACEis in the 2001 Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT). In this trial, valsartan was established as an alternative to ACEis in patients who were intolerant of ACEis. Since ACEis block the enzyme that breaks down bradykinin, they can cause a dry, hacking cough. This is not a side effect of ARBs since they do not block ACE.

The new kid on the block, Entresto®, was actually shown to be superior to enalapril in reducing HF-related hospitalizations and deaths (hence its new status as a first-line option). Greatest morbidity and mortality benefit has been shown in those with NYHA class II or III HF, and it is recommended those in these classes on an ACEi or ARB be switched to the ARNi.

Notice how I’ve always separated these classes with “OR”. You only get to pick ONE. Using these drugs together can cause serious side effects like renal dysfunction, hypotension, and hyperkalemia. In fact, a 36-hour washout period is required between an ACEi and ARNi when switching therapies to avoid these side effects.

BTW, what is the mechanism? And how does it affect the Frank-Starling curve?

Each time we give an ACEi or ARB, we decrease the circulating angiotensin II (a vasoconstrictor) which effectively make ACEis and ARBs vasodilators.

BUT angiotensin II also causes cardiac remodeling. By blocking it, we slow, stop, and sometimes reverse cardiac remodeling. Giving too large a dose up front can cause sluggish renal flow, so to avoid this we slowly titrate these up.

In the case of our ARNi, we add a neprilysin inhibitor. Neprilysin degrades brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). By inhibiting their metabolism, sacubitril blocks neprilysin and therefore raises BNP and ANP levels which helps maintain cardiac function.

BB

You’ll notice every time I’ve referenced BBs I’ve added “GDMT” in front of it. This is because you can’t just stick any ol’ BB in your patient’s HF regimen and call it a day. Only three have been proven to decrease mortality: bisoprolol, carvediol, and metoprolol succinate (we want the extended-release metoprolol, NOT the immediate-release one (tartrate)!). BTW, professors LOVE to use this as a test question (and it may even pop up on your NAPLEX!).

Again, we have the target dose issue. Only it’s harder. If you start a full-dose BB on a patient with HFrEF, you will cause ADHF.

That’s right, the BB to treat HF will cause worsened HF. In fact, when I (Dr. Barnes) began in healthcare, giving a BB in HF was considered malpractice, now it is the standard of care and NOT giving it is malpractice.

BBs are NEGATIVE inotropes. So, if you look at that lovely picture of the Frank-Starling curve from earlier in this post, you see the inotropes push the curve up. A negative inotrope will push the curve downward.

That is why it was malpractice in HF in the past, and adding it in ACUTE HF would likely be malpractice also.

The BB block beta-adrenergic effects of catecholamines (see the second post in this series). In ADHF, the beta-adrenergic effects are what is keeping the patient alive (in fact, we give vasopressors and inotropes to mimic this in ADHF).

But the continued bombardment of catecholamines causes the heart to continue to work hard well beyond its intended fight-or-flight mechanism and eventually are no longer needed. By SLOWLY titrating up (doubling about every two weeks) until reaching the target dose, we eventually remove this adrenergic distress.

Another Clinical Pearl: as we increase the dose, the heart upregulates the B1 receptors, increasing their numbers, so more BB is needed to get the same effect. Abruptly stopping a BB in a patient that has upregulated beta receptors can actually precipitate ischemia, injury, and infarction.

So don’t stop the BB abruptly, titrate it downward if the patient presents with acute on chronic HF. Stopping a high dose cold turkey could trigger a myocardial infarction (MI).

MRA

The two choices here are spironolactone and eplerenone. From my (again, Dr. Barnes) experience, there is no advantage in HF for one over the other. Spironolactone is easier on the wallet (eplerenone is a bit wallet toxic). But spironolactone is structurally similar to estrogen and may cause gynecomastia.

I would reserve eplerenone for patients who can afford it and have symptoms of gynecomastia on spironolactone (usually starts with breast tenderness). We still want K to be < 5 mEq/L (and, frankly, I would be very cautious if it was greater than 4.5 mEq/L) and eGFR to be > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The mineralocorticoid receptor is a nuclear receptor, which means when medication is given, there will be a delay in effect. The previous products of transcription are still present, but no new products will be made. The old products of transcription will be translated, will have their effect, and then will eventually be degraded. We usually do not see an effect for a few days.

Spironolactone and eplerenone are also potassium-sparing diuretics but, in HF, you should think of them as aldosterone antagonists which have a side effect of diuresis.

SGLT2i

But wait, aren’t those for diabetes?

Yeah, they were. But studies show value for these drugs in HF, regardless of whether or not the patient is diabetic.

If you think back to your diabetes lectures, you’ll probably remember the primary mechanism by which these drugs lower glucose is diuresis. This diuretic effect is also what makes them useful in HF. By increasing urine output, we are lowering the blood volume (AKA the preload) and reducing the workload on the heart.

There are three SGLT2is approved for HF. Two you are probably familiar with, and one may be news to you. The two I sincerely hope you’ve heard of are empagliflozin (Jardiance®) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga®). Sotagliflozin (Inpefa®) was approved more recently. It’s actually the first dual SGLT1/2i (meaning it inhibits both SGLT 1 and 2).

Another SGLT2i (canagliflozin (Invokana®)) isn’t specifically indicated for HF but has been shown to reduce the risk of HF hospitalizations in certain diabetic patients. There are a couple more SGLT2is on the market, but they are not currently approved for HF and are outside the scope of this article.

Diuretics

The last class in our HF backbone is diuretics. Diuretics are incredibly important in fluid overload and may result in avoiding a hospitalization or decompensation, but they do not work to reduce mortality. All we are doing is improving symptoms and quality of life (QoL). All the other drugs we talked about in this section have been shown to reduce morbidity and/or mortality.

Loop diuretics are preferred for most patients with HF, although thiazide diuretics may be used in certain patients. We typically use furosemide (Lasix®) for diuresis. Just remember that it lasts six hours, so don’t give the last dose of the day within about six hours of bed time or your patient will be up all night.

Seriously, don’t do this to your poor patients. Make sure that Lasix is scheduled appropriately!

The Drugs We Keep in the Palm of Our Hand

Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (BiDil®)

Here’s a little pearl for your next trivia night: BiDil® was the first drug to receive a race-based indication. If you peek back at the handy flowchart I provided from the 2022 guidelines, you’ll see this drug is indicated for African American patients with persistent stage C HFrEF, NYHA class III-IV. According to the FDA, it’s not as effective in other populations.

It’s a combination of two drugs: hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate. These are both vasodilators and will push the Frank-Starling curve upward. It recently-ish (2022) became available as a generic.

Additional add-on therapies

Once GDMT is optimized, these additional therapies may be considered:

Treatment of Other Types of Heart Failure

We focused on HFrEF in this article, but treatment of the other types of HF are really quite similar, the biggest difference being that BBs aren’t recommended for HFpEF patients.

HF Pharmacotherapy Summary

And there you have it! The HF guidelines have changed a lot in recent years, but hopefully this article helped you wrap your head around the current recommendations. Here’s the gist of it:

Backbone of therapy for chronic, stage C HFrEF: ARNI OR ACEi OR ARB + GDMT BB + MRA + SGLT2i + diuretics as needed. These may be started simultaneously or sequentially at low doses and titrated to target doses (table 14).

May add hydralazine + isosorbide dinitrate (BiDil®) and/or other add-on therapies for select patients. Recommended therapies for comorbidities (e.g., anemia, diabetes, hypertension, etc.) are also addressed in the guidelines.

Get this Series as a PDF!

Want a printer-friendly version of the ENTIRE heart failure series? Or do you just want to save the series for offline viewing? You can now get the entire Heart Failure Series as a single (and attractive) PDF. PDF currently under construction as this series is being updated!