An Overview of Pharmacotherapy for Insomnia

(Image)

Steph’s Note: We’ve all had that night. The one where you stare at the clock on the nightstand for hours on end because you just. Can’t. Get. To. Sleep. Or you initially fell asleep, but you woke up at 3am and then couldn’t get your eyes to stay shut from then after. You try every trick you’ve ever heard of, from literally counting sheep to imagining a blank whiteboard, but you only get increasingly annoyed and desperate as the minutes - and then hours - tick on by.

Yeah, been there. But at what point does this become a true problem? After how many nights like those does a person need to consider talking to a provider? What about trying medication, and if so, what are the options?

These are the questions we’re going to try to lay out some answers to in this post. Insomnia has historically been (and kind of still is, tbh) an elusive entity, and we certainly don’t have ALL the answers yet. But we can work with what we have to do the best we can! So let’s see what we DO know.

What is Insomnia?

The term “insomnia” get thrown around a LOT. From the one night of lost sleep right before a big exam, to the months on end of broken sleep, people seem to use this term somewhat haphazardly. Which is fine, but it’s important to have a clinical understanding of the definition too.

According to the 2014 International Classification of Sleep Disorders, the definition of insomnia has several components:

Trouble initiating or maintaining sleep, AND

Associated daytime consequences, BUT WITHOUT

Clear environmental causes or insufficient chances to sleep.

Am I the only one that would absolutely wear these? I’m not just talking about for bed either. I’m talking inclusive of dog walks around the block on cold mornings. Yessss. (Image)

Basically, insomnia is NOT trouble sleeping because your roommate is throwing a rager in the room next door (because, clearly, he’s not in pharmacy school!). It’s also NOT because your heater broke today and you’re freezing in your thickest fleecy onsie footie PJs until the maintenance tech comes tomorrow. In these cases, there are obvious environmental causes for the inability to sleep.

For the purposes of definition, we should also cover some additional terminology needed to interpret clinical studies within this arena. First, sleep latency (SL), aka sleep onset latency, refers to the time it takes a person to go from being awake to fully asleep. So this would relate to the trouble initiating sleep mentioned above. Second, sleep maintenance (SM) is the ability to stay asleep for the desired or intended amount of time. A couple other commonly-used measures include the following:

Total sleep time (TST): Literally the amount of time actually spent sleeping in a given night.

Time spent in bed minus sleep latency and minus any overnight awake times

Wake after sleep onset (WASO): The total amount of time spent awake after initially falling asleep

Quality of sleep (QOS): Self-explanatory, measured by various patient-report tools

Sleep efficiency (SE): The percentage of time in bed actually asleep (basically TST in percentage form)

Number of awakenings (NOA): Also pretty self-explanatory, the number of times a person awakes after falling asleep

Alright, now that we have the terminology out of the way, and we’re all on the same page…

Insomnia can also be short-term or chronic, with the threshold being symptoms occurring at least 3 times a week for either less than or greater than 3 months in duration, respectively. So this is important, right? Sleeplessness doesn’t have to be an every night occurrence to classify as true insomnia. It’s a minimum of 3 times a week. (Makes you think about your own sleep habits, doesn’t it?)

On this note, how many people actually suffer from true insomnia?

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, up to 50% of the US population experiences short-term insomnia, and up to 10% of people in industrialized nations meet criteria for chronic insomnia. Think about how you feel when you lose sleep for just one night? What does that do to you the next day?! Now just think about all the folks who are experiencing this at least 3 times a week for months on end??

Makes you a little more nervous to hop in the car and go for a drive on the interstate, doesn’t it? Yeesh!!

We’re not all this cute or sweet when we’re this tired… (Image)

Chronic insomnia has definitely been shown to have effects on function and quality of life. Thank you, Captain Obvious. We’ve all experienced these types of effects at some point, from being less efficient or effective at work (or even calling out) to messing up an exam or wrecking a responsibility - no matter how many cups of coffee you pound the next morning. We’ve all heard of the truck drivers pushing through on their routes to make deadlines, getting sleepy, and then there being an accident. Rates of vehicular and occupational accidents are certainly impacted by insomnia.

But what about some of the less obvious consequences of insomnia?

These include effects like development of psychiatric disorders, e.g., mood disorders, including depression or even psychosis. It could actually turn into more than just the day of grumpiness afterwards. Even lesser known than the psychiatric effects are the potential physical consequences. Yep, sleep doesn’t just affect your mood and efficiency at work the next day. There have been studies linking chronic insomnia with increased risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease!

Now that we know what the clinical definition of insomnia is as well as what the various consequences can include, how do we mitigate (or #lifegoal, eliminate) this issue for patients?

Treatment Options for Insomnia

Non-pharmacologic Management

Yes, this is a pharmacy-based website, and we do love to talk about drugs! But we really can’t ignore the obvious when it comes to insomnia, which is that not everyone who has a difficult time sleeping needs to immediately jump to a new medication. As pharmacists, we should First Think Drugs (FTD!).

Are we already giving a patient a medication that is actually contributing to his insomnia?! Have we done a complete medication history, only to find out that Mr. Smith is taking his furosemide at bedtime and getting up 4 times a night to urinate? So don’t forget to be a scrutinizing pharmacist first!

Simultaneously, you and your team can consider non-medication, medical causes for lack of sleep. Is the patient suffering from sleep apnea affecting quality of sleep? Is it a prostate issue causing urinary problems? GERD from lying flat making her sleep in a less comfortable position? Does the patient describe symptoms consistent with restless leg syndrome?

There are TONS of medical reasons someone may have difficulty sleeping, which is why listening to our patients is so crucial.

Now, once we’ve attacked possible pharmacy and medical causes of insomnia, we may still not have found the key to improving our patient’s sleep. BUT that still doesn’t necessarily mean we have to use a medication. And even if we do end up using pharmacotherapy, that doesn’t mean it has to, or should, be a permanent intervention! Sometimes less really is more when it comes to initiating pharmacotherapy.

So, step #1 is to reach for nonpharmacologic strategies. Check out some of these methods from the American Family Physician:

(Image)

Wow. Seriously LOTS of options at a person’s disposal before reaching for pharmacotherapy!

But sometimes, it still just isn’t enough. Maybe these nonpharmacologic strategies help, but a person is still experiencing some degree of impactful insomnia. Or perhaps these methods just aren’t helping at all. It’s at this point that we may consider adding a medication, but we should also always be considering whether continued treatment is still necessary down the road.

Pharmacologic Management of Insomnia

Now on to the fun pharmacy stuff!

There are MULTIPLE medications and classes of medications available that may assist in improving a patient’s insomnia, and not all sources agree with regards to how the pharmacotherapy arsenal should be used. So we’ll talk about some general recommendations and present a couple of approaches, but please know that insomnia is very much not a one-size-fits-all situation.

For example, here’s how the 2017 American Family Physician (AFP) group approaches treatment of insomnia:

(Image)

For kicks and giggles, to compare and contrast, let’s take a look at how insomnia treatment is presented by Up-to-Date authors:

(Image)

Note how both algorithms consider whether the issue is with a patient’s sleep latency, sleep maintenance, or both. Also very important is the use of non-pharmacologic methods before proceeding to pharmacotherapy. However, you should also note the differences in inclusion of various medication classes as well as the reliance on OTC sedating medications as well as on some antidepressants that is not necessarily found in the AFP algorithm.

You may be asking yourself, “What does the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) - aka the expert group - think about one drug versus another?”

Here’s what the AASM has to say in their 2017 guideline: “This guideline is also not intended to recommend one drug over another…The selection of a particular drug should rest on the evidence summarized here, as well as additional patient-level factors, such as the optimal pharmacokinetic profile, assessments of benefits versus harms, and past treatment history.” So due to the lack of head-to-head comparison trials, AASM hasn’t yet made a specific if-this-doesn’t-work-then-try-this algorithm.

Where does this leave us as pharmacists?

Well… we may not know exactly how to leverage the arsenal of insomnia treatments, but such is the case for many other disease states (e.g., multiple sclerosis)! So what we have to do in these cases is know enough about the medications to determine what may fit best for a patient - and which ones would absolutely not be a good fit for specific reasons.

This is where tl;dr comes in. Let’s talk about the drugs.

(Dual) Orexin Receptor Antagonists (DORAs)

This relatively new medication class has two members: suvorexant (Belsomra, FDA-approved 2014) and lemborexant (DayVigo, FDA-approved 2019). These medications work by blocking the action of orexins (aka hypocretins). There are two types of orexin, orexin A and orexin B, and these neuropeptides bind to their hypothalamic neuronal receptors, orexin-1 receptor (OX1-R) and orexin-2 receptor (OX2-R). The actions of these neuropeptides and their receptors typically play a role in maintaining wakefulness, and deficiencies in normal activity are associated with narcolepsy.

By blocking orexin activity at their receptors, DORAs inhibit the normal arousal system that leads to wakefulness. By inhibiting wakefulness, the hope is these medications simply allow for continued sleep rather than putting somebody to sleep. This is a subtle difference but perhaps a key one when it comes to limiting adverse effects like rebound insomnia, which can occur when other classes of medications are discontinued.

Both DORAs are indicated for insomnia due to issues with sleep latency and sleep maintenance. They should be taken within 30 minutes of bedtime when a person knows they have at least 7 hours to devote to sleep. Taking either with food or when food may still be sitting in the stomach may lead to delayed onset of action, so that’s an important counseling point!

(Image)

These medications are intended for short term use (max 8 weeks) in combination with non-pharmacologic therapies, although with the lack of withdrawal observed in studies, it’s possible for a person to remain on these longer (if needed). Clinical studies noted some daytime somnolence at higher doses of suvorexant, but it usually was not enough to lead to medication discontinuation. Since approval, however, reports of worsening depression, including suicidal ideation, as well as what’s been dubbed “complex sleep behaviors” have arisen with both DORAs. These are the scary stories of patients engaging in activities while not fully awake, including eating, cooking, driving, making phone calls, and even having sex.

While the 2am snack may not be the biggest deal in the world for everyone, I once had a patient who had severely burned both of her hands on her stove while sleep-cooking. And let’s not even get into how scary the sleep-driving is.

Lemborexant also carries warnings of nightmares and abnormal dreams, sleep paralysis (which is when someone can’t move for several minutes during sleep/wake transitions), hypnopompic hallucinations (hallucinations when awakening), and cataplexy (loss of muscle tone often triggered by strong emotions).

A few more key pharmacist points: DORAs are metabolized by CYP3A4, so you better check for drug interactions! Attention to various dosing adjustments for renal and hepatic impairment is essential for both.

Benzodiazepines (BZDs)

The benzodiazepines, aka the benzos, encompass the original hypnotic medications. There are five BZDs approved by the FDA for treatment of insomnia:

Estazolam (Prosom)

Flurazepam (Dalmane)

Quazepam (Doral)

Temazepam (Restoril)

Triazolam (Halcion)

(Of course, there are other BZDs, including our old frenemies lorazepam, midazolam, and diazepam, but those are not indicated in the treatment of insomnia. So those are not the focus of this post.)

BZDs work by binding to post-synaptic GABA neurons and enhancing their inhibitory effects by allowing for chloride-induced hyperpolarization. This hyperpolarization means it’s harder to reach the action potential threshold, which in turn means that neuron is more stabilized. This action is thought to occur at GABA-A receptors rather than GABA-B receptors. So basically, by agonizing GABA-A receptors, BZDs favor sleep.

Unlike the DORAs, which have similar indications and relatively similar pharmacokinetics, the hypnotic BZDs exhibit much greater variability. With regards to targeted uses, temazepam is the only one that is recommended for both sleep latency and maintenance, likely due to its favorable balance of a shorter time to onset of action but still longer half life and duration of action. Triazolam is recommended for those with sleep latency difficulties, and estazolam, flurazepam, and quazepam are all largely for sleep maintenance troubles.

Now, you likely noticed that there weren’t any BZDs listed on either of the above AFP or Up-to-Date therapy algorithms, so what’s the deal with that if they’re such great sedatives?

Basically, the risk usually outweighs the benefit with these agents. They’re certainly prominent, reigning members on the Beer’s List and should be avoided in older adults due to risks of falls and behavioral changes, such as paradoxical aggression and hyperactivity due to disinhibition. Patients with sleep apnea may not tolerate the associated respiratory depression, so that’s not a good combination. When respiratory drive is already abnormal, let’s not make it worse!

Due to their potential to cause dependence, they are controlled substances (C-IV) and should be avoided in those with a history of substance abuse. This dependence also means a risk of rebound insomnia and withdrawal after medical cessation, which in the case of BZDs can include symptoms as severe as seizures and death.

So definitely lots of issues with BZDs. But they may be useful for a limited period of time in certain younger patients who have tried and failed other medications. Even more than this, it’s important for us to review and know the history of a given treatment strategy, so we can look to its future… which in this case means the benzodiazepine receptor agonists.

Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists (BRAs)

The benzodiazepine receptor agonists, aka the “z-drugs” or the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, include eszopiclone (Lunesta), zolpidem (Ambien, Intermezzo), and zaleplon (Sonata). These are often the insomnia medications that most people are familiar with, as reflected by their incorporation into both of the above organizations’ insomnia management algorithms. So what makes them so special?

Great question.

Perhaps Barney, but perhaps not… (Image)

Like their namesakes the benzodiazepines, the BRAs bind to GABA-A receptors, leading to hyperpolarization and neuronal stabilization. What makes them different is their apparent further selectivity for subunits of the GABA-A receptors, which is thought to account for fewer anxiolytic and increased sedative effects, as well as a more limited range of side effects. Basically, they tried to create the “new and improved” BZD to specifically target sleep without as much collateral damage.

Eszopiclone and the Ambien formulations of zolpidem are recommended to help with either sleep latency or maintenance, whereas zaleplon is really most useful for sleep latency because of its very short half-life - only about 1 hour. (Remember the general rule of thumb: 5 half-lives to get to steady state after starting a drug and the same to get a drug fully out. Assuming one would like to sleep the usual 7-8 hours per night, zaleplon’s estimated 5 hours to be completely eliminated just isn’t gonna cut it for most people!)

The Intermezzo formulation of zolpidem is only indicated to help with nighttime awakenings. Its sublingual design allows for quicker absorption and onset than its immediate- and controlled-release counterparts. That being said, the half-life is still about 2.5 hours, so patients should be counseled to only use doses of this if they still have at least 3-4 hours left to dedicate to sleep. Otherwise, prooooobably not gonna wake up for that alarm.

So have the z-drugs lived up to their intended design of fewer adverse effects?

Wellll, they still carry the reports of “complex sleep disorders” as discussed earlier with the DORAs. These typically occur at higher doses, much like the more common reports of memory impairment, headache, dizziness, GI upset (mostly nausea and abdominal pain), and hallucinations. They also run the risk of dependence, especially due to the feelings of euphoria and remaining anxiolysis they can produce.

So they definitely still carry their fair share of adverse effects, but with data demonstrating double the improvement in sleep latency time compared with placebo, their effectiveness sure does come in handy for many patients.

Melatonin and Its Receptor Agonists

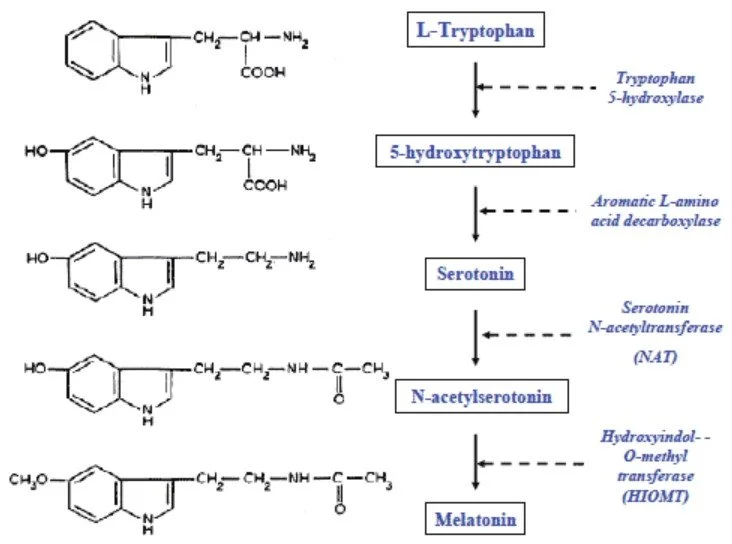

The next pharmacotherapeutic target that is common to both algorithms is the melatonin receptor. It may be agonized either by melatonin itself or by medications developed to mimic’s melatonin action. So what exactly is melatonin, and how does it work?

Interesting… melatonin synthesis occurs via a rather familiar Thanksgiving entity - tryptophan, and it also takes a detour to our old friend serotonin! (Image)

Melatonin is a naturally-occurring hormone produced by the pineal gland in response to observed light levels. Synthesis and secretion follows a cyclical pattern with levels increasing starting at sundown and peaking between 2-4 am. Levels then decrease over the course of the rest of the night, until the whole thing starts all over again the next evening. This hormone is responsible for regulating the sleep-wake cycle by binding to MT1 and MT2 receptors, which are 2 subtypes of the ML1 high-affinity melatonin receptor.

Administering exogenous melatonin induces fatigue and improves sleep latency, but it doesn’t necessarily do a whole lot for sleep maintenance throughout the remainder of the night. Doses are extremely variable - from 200mcg to 20mg - but it’s generally recommended to start with no more than 3mg at bedtime as lower doses may be just as effective as higher doses if taken properly. What does “properly” mean? It means it’s best taken several hours prior to bedtime to try to augment the natural melatonin circadian cycle.

Of note, more is not always better, and melatonin is no exception. Escalating doses too quickly or too high may produce the opposite of the desired effects, including worsening insomnia, headache, nightmares, and daytime drowsiness. So just because 5 mg is working doesn’t mean that 10mg will be any better, and then spiraling up to 20mg STILL may not help with sleep - but it may start producing unwanted effects.

The other difficult part about using straight melatonin is that, in the United States, melatonin is considered an over-the-counter dietary supplement. So formulations aren’t regulated to the same degree as medications, meaning what’s on the label of a supplement bottle isn’t always necessarily what’s actually in the bottle. It’s important that people understand the possibility of variation in a bottle and/or be counseled to look for brands that are verified and tested by a 3rd party quality control entity!

Melatonin is also available in a controlled-release formulation, which in one 2013 study, decreased sleep latency, increased total sleep time, and resulted in better quality sleep. But again, it is only available as a supplement in the US, so it’s unclear whether benefits apply to all formulations or just the one that was used in that study. But given it may have some benefits for a lot less money than the synthetic melatonin receptor agonist we’re about to talk about, maybe it’s worth a chance…

Ramelteon (Rozerem) is the only melatonin receptor agonist available in the US. Compared to its supplement counterpart, it only needs to be administered about 30 minutes before bedtime as opposed to hours. This enhanced effect on sleep latency is thought to be due to ramelteon’s six-fold higher affinity for MT1 receptors than melatonin. Taking too close to a high-fat meal can delay the time to peak effect and also decrease the peak concentration, so it should be taken only with a small snack (at most) or ideally on an empty stomach.

Because it’s one of the few - or possibly - only prescription sleep aids that doesn’t cause dependence or have abuse potential, ramelteon is also one of the (very) few that is NOT a scheduled controlled substance.

Antidepressants

We’ve all seen the internal medicine patient medication list that has that low-dose trazodone or amitriptyline (or nortriptyline) ordered QHS. When you research the mechanism, you probably noticed that they’re actually antidepressants and the doses for that indication are much larger than what’s on your patient’s list. So what’re these antidepressants doing masquerading as bedtime sleep aids?

Well, it’s honestly a case of exploiting a medication’s side effects for therapeutic purposes. This isn’t really a new idea. In fact, it even has a name: drug repositioning. This refers to when we take a drug that has an (initially unwanted) side effect and then repurpose it to use that side effect for therapy. One pretty famous example is sildenafil. It was originally investigated as an antihypertensive and was targeted towards use for angina; however, one of the side effects observed in studies was male erections. And guess what, now sildenafil (Viagra) is one of the leading treatments for erectile dysfunction.

So within the antidepressant class of insomnia treatments, we have trazodone (classified as a tricyclic-like antidepressant) as well as the true tricyclic antidepressants, e.g., amitriptyline (Elavil), nortriptyline (Pamelor), etc. There’s also a lesser-known TCA that actually carries FDA approval for insomnia, doxepin (Silenor). Even though we’re not 100% sure what to do with trazodone’s classification, it has a similar enough mechanism to throw in a bucket with the true TCAs for our purposes here today.

The TCAs aren’t necessarily the most favored of antidepressants these days, and this is largely due to their extremely non-selective natures. No lie - they hit no fewer than FIVE different neurotransmitter pathways, including inhibiting serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, alpha 1 and alpha 2 antagonism, muscarinic antagonism, and histamine blockade. The degree to which each individual medication acts on each of these paths culminates in its effectiveness for depression as well as its potential adverse effects.

When it comes to insomnia, the histamine receptor antagonism is the action that produces sedation rather than anything related to being antidepressants. But at what costs, when there are potentially so many other receptors in play?? Trazodone and the TCAs are associated with other unwanted effects like orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, confusion, and the anticholinergic repertoire:

Can’t see (blurry vision),

Can’t spit (xerostomia or dry mouth),

Can’t pee (urinary retention),

Can’t…poop (constipation).

The slight exception to this TCA side effect profile for insomnia is doxepin, which is why it’s the one TCA that’s actually FDA-approved for this indication. At the very low doses approved for insomnia (3 and 6 mg), it’s pretty selective for its antihistamine effects without having many effects on the other neurotransmitter pathways. Hence, we get the desired sedation without much concern for the other issues. Seems like a beautiful solution, right?

Well it would’ve been if those very low doses weren’t so much more expensive than the generic 10mg formulations! The generic 10mg capsule is $0.50-0.75 a piece, but the doxepin 3 and 6 mg tablets are ~$16-17/tab! Talk about a markup… And of course the generic cheaper formulation is a capsule, so it can’t be split. OF COURSE. There is also a concentrated 10mg/mL liquid formulation that runs about $0.40 per mL, which isn’t too shabby if patients are ok measuring out their doses. So sometimes prescribers (and patients) try to make doxepin more affordable by using the higher strength generic capsule, but then the tradeoff is monitoring for those side effects as additional receptors may come into play.

Antihistamines

And now we come to it, our final class of insomnia medications. Or maybe I should actually say, the final class of medications used for insomnia. Because calling them “insomnia medications” makes it sound way more kosher than it actually is…

It’s historically been fairly common practice to use first generation antihistamines, like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and doxylamine (various “PM” formulations). They’re cheap, easily accessible as over-the-counter medications, and well, for most people, it’s true, they are sedating. (A smaller percentage of people have a paradoxical reaction to diphenhydramine. Instead of getting sleepy, it actually hypes them up and makes them jittery! This opposite reaction is thought to be a result of being a CYP2D6 ultra rapid metabolizer, resulting in rapid production of an excitatory metabolite.)

So why are these seemingly easy and relatively safe medications NOT actually recommended for use in insomnia for most patients?

These older generation antihistamines are also fairly anticholinergic as well, often leading to those other less desirable “anticholinergic repertoire” effects mentioned earlier with the TCAs. They can also cause confusion, especially in the elderly, and are certainly members of the famed Beers Criteria. One of the other unwanted effects is increased intraocular pressure, so these shouldn’t be used in patients with open-angle glaucoma either.

Who may benefit from antihistamines for insomnia?

Pregnant women! Neither diphenhydramine nor doxylamine has been associated with increased risk of harm to the baby during pregnancy. So they may be useful options for this population, when the previous options have either been shown to cause harm - or when we just don’t have the info.

Just because they’re over-the-counter doesn’t mean they’re benign! (This is so true of MANY medications!!)

The tl;dr of Insomnia Pharmacotherapy

So there you have it! The main arsenal of pharmacotherapy for insomnia. While there are of course other medications that can cause sedation, including antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and even an antihypertensive (clonidine), use of these for insomnia is limited to those who also have the originally intended indication for those medications. So we don’t just throw around olanzapine willy nilly for plain insomnia… A patient should have a true indication for olanzapine, whether that’s schizophrenia or bipolar, etc.

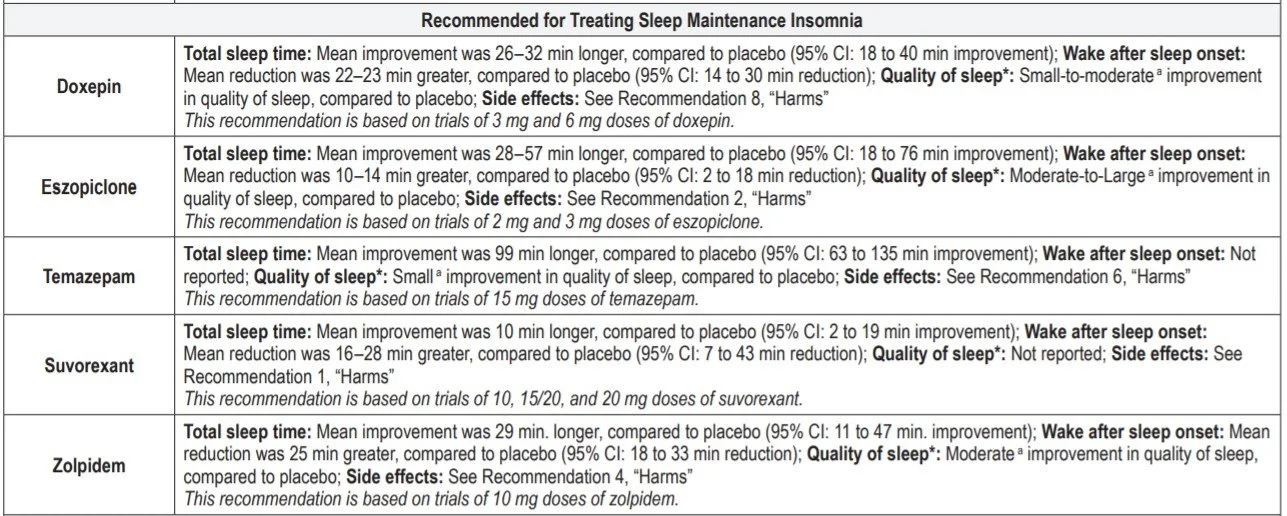

I would like to end with this summary chart from the AASM, which will hopefully help you to keep track of which specific sleep measures each of these options may improve. Remember, there’s not yet one particularly accepted strategy for how best to leverage all of the options, but it IS important to consider the sleep issues each medication targets based on mechanism and pharmacokinetics, cost/accessibility, potential dependence issues, and adverse effect profiles. Happy dreams for you and your patients!

(Image)