An Introduction to Pediatric Infectious Diseases

Steph’s Note: Today we introduce a new blogger to the tl;dr family! Heather Honor is a current P4 student at the University of Connecticut’s School of Pharmacy. She originally graduated from the University of New Haven with Bachelor’s Degrees in Forensic Science and Chemistry (um, very cool!) but then found her calling in the field of pharmacy. Her pharmacy passion lies in pediatrics, and she hopes to specialize during residency training. She fuels this passion now as a member of the pediatric pharmacy association (PPA). So, here’s Heather to share a smattering of her pediatric love!

Welcome to the world of pediatric pharmacy! While things are often bright and cheery with bright giggles and screeches of excitement, even the littlest of the little ones get sick. For all of these little humans, the most important piece of advice to remember is that children are not tiny adults. Through constant changes and growth, both mental and physical, pediatric patients need just a little extra TLC.

In that vein, before we jump into pediatric infection topics, let’s just quickly go over some necessary details:

Now that we have these basic principles out of the way, time to move onto some infections!

Acute Otitis Media

“Ouch!! My ear!” Pediatric patients commonly suffer from ear infections, also known as acute otitis media. Children often present with unusual irritability, increased difficulty sleeping, fever, or ear tugging.

There are three common pathogens implicated in AOM:

Streptococcus pneumoniae, a gram-positive cocci, is the most common culprit, followed by

Haemophilus influenzae (but with increases in pediatric vaccination campaigns, the infection rate with H. influenzae has significantly decreased), followed by

Moraxella catarrhalis, a gram-negative diplococcus, which is a not so common but possible option.

Not all AOM infections need to be treated. (Wait - we don’t always treat an infection with antibiotics!?!) For patients with non-severe symptoms and no otorrhea (drainage), there is a possibility for observation only. Also, patients aged 6-24 months with unilateral infections or those older than 24 months have this option of observation only.

Now what about when we DO need to treat with antibiotics… What are our choices?

Amoxicillin is a first-line agent to treat AOM in children. Dosing is 80-90 mg/kg/day divided into 2 doses. But wait a second… you might be asking yourself, what if the child is older and weighs more? One thing we need to remember with weight-based dosing in children is adult maximum dosing or maximum dosing, in general. For amoxicillin and AOM, the max is 2,000 mg/dose or 4,000 mg/day.

Great, amoxicillin, CHECK! But what if the patient recently had antibiotics, increasing the risk of a resistant microbe, or if the patient is allergic to amoxicillin?

This is when we consider amoxicillin-clavulanate. Dosing for amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) is 90 mg/kg/dose of the amoxicillin component divided in 2 doses. Some common concentrations are 200 mg-28.5 mg/5 mL, 250-62.5 mg/5 mL, and 400 mg-57 mg/5 mL, but know that the 200 and 400 mg/5 mL versions contain aspartame, which has phenylalanine (caution in phenylketonurics!).

There’s also another formulation, Augmentin ES, that purposefully contains less clavulanate per amoxicillin dose: 600 mg-42.9 mg/5 mL. Long story short, definitely pay attention to which concentration you’re ordering and the individual components!

Not all Augmentin concentrations are okay for children, mainly due to side effects caused by clavulanate. As patients go over 6-7 mg/kg/day of clavulanate, they can experience increased side effects, mainly diarrhea. When choosing the formulation, one must consider the amount of amoxicillin that is needed, as well as how much clavulanate comes with the chosen formulation. Augmentin formulations are in varying ratios of amoxicillin (AMOX) to clavulanate, 14:1, 7:1, and 4:1. (So for example, the 14:1 formulation has 600mg amoxicillin + 42.9 mg clavulanate in every 5 mL of suspension.)

See below for a few extra pearls about each one!

If the patient is allergic to penicillin, other options include cefuroxime or ceftriaxone. Dosing for cefuroxime for infants at least 3 months old is 15 mg/kg/dose twice daily for 10 days for the oral suspension. For patients old enough to swallow tablets, cefuroxime can be given as 250 mg twice daily for 10 days.

Ceftriaxone is only available IV or IM. Dosing for ceftriaxone in children > 28 days (i.e., older than a neonate) is 50 mg/kg/dose once daily for 1-3 days (max of 1,000 mg/dose). If the AOM is persistent or relapsing, it’s recommended to do the full 3 day course.

So why can’t you give neonates ceftriaxone? Great question!

In the littlest ones, ceftriaxone is able to displace bilirubin from albumin. This can lead to an excessive buildup of bilirubin in the blood. Symptoms include yellow-tinged skin, mucous membranes, or even in the whites of the eyes. Ceftriaxone’s displacement of bilirubin can also lead to a buildup of bilirubin in the brain, known as kernicterus. Although rare, symptoms include lethargy, poor feeding, and vomiting. Some neurological consequences include spasticity, absence of certain reflexes, and muscle spasms. In order to help prevent this reaction from occuring, it’s NOT recommended to use ceftriaxone in neonates.

Strep Throat

Oh no, not strep throat! How do these patients present?

The most common complaints that accompany a diagnosis of strep throat (aka strep pharyngitis) are a terribly sore throat with trouble swallowing, headache, fever, and even bright red swollen tonsils that could have white patches or streaks of pus. Some patients may also present with a rash, which is known as scarlet fever (for all you fans of 19th century literature!). Although strep throat seems like a fairly mild and localized infection, if left untreated in pediatric patients, it can progress to rheumatic fever - which is more serious and consists of painful, tender joints and even cardiac consequences like heart murmurs or pericardial effusions. Group A Streptococcus, aka Streptococcus pyogenes, is the organism that causes this infection.

(Image)

Diagnosis of strep throat includes a physical exam of the child, review of the signs and symptoms, and a rapid strep test. Given the sensitivity of the rapid strep test can be relatively low (reportedly ~86%), there is a very real possibility of false negatives. It luckily does have a high specificity (~95%), so there are very few false positives. So if the rapid strep test is positive, you can feel pretty confident that’s the diagnosis; if the test is negative, there’s still a chance the patient could actually be positive. For a more definitive diagnosis, a throat culture is often performed in pediatric patients, which takes longer but is more accurate.

(For a review of sensitivity and specificity, check this out!)

So now that we know what strep throat is and how it’s diagnosed, how do we manage it?

Well first, unlike AOM, this is not a case where observation is an option. Even though strep throat can be self-limiting, the possibility of some of those nasty sequelae makes it far more beneficial to just treat the infection. For patients without a penicillin allergy, penicillin V is a solid option. For children < 27 kg, give 250 mg 2-3 times daily for 10 days. (Yes, the recommendation actually leaves variability in the number of times per day. Consider the patient’s - and parent’s - ability to adhere to the medication, as well as perhaps the severity of the case.) If the child is ≥ 27 kg, the dose is 500 mg 2-3 times daily for 10 days.

For non-severe penicillin allergies (e.g., mild rash or itching), first generation cephalosporins may also be options for strep throat treatment. How do we know whether a patient will have a reaction to a certain cephalosporin if they reacted to a penicillin?

Cross-reactivity, everyone’s nightmare. Important thing to remember is that it’s always worth double checking if you are unsure. This chart goes into more detail about which beta lactams may not good ideas to try in patients that have exhibited sensitivities. It focuses on similar side chains. The “X” indicates when two beta-lactams have similar side chains and therefore may cause cross-reactivity:

(Image)

If the patient has experienced a true penicillin allergy (e.g., anaphylaxis), the usual go-to for strep throat treatment is azithromycin 12 mg/kg/day once daily (MAX: 500 mg/dose) for 5 days.

We have discussed some antibiotic treatments, but any of these can take a few days for children to symptomatically improve. So how can we help them feel a little better in the meantime?

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) may be used for fevers (stay tuned for dosing). Remember, do not administer aspirin-containing products to children given the concern for Reye’s Syndrome, which can cause brain and liver damage. Some soothing measures for a sore throat for children over 1 year of age include warm liquids (like chicken broth). For children over 4 years old, throat lozenges may be an option, although certainly they should be closely monitored! Always remember to read the labels to ensure any symptomatic management products are recommended for the patient’s age as each is different.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

*Cough* *Cough* Hmm that’s weird, the baby is coughing…a lot. Time to go to the doctor. The doctor says, “This child has RSV.” What’s that?

RSV, aka respiratory syncytial virus, is a common infection in children less than 1 year old. Some of the symptoms include a runny nose, decrease in appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and even wheezing. Most children suffer from this by the time they are 2 years old. RSV can easily be spread through coughing or sneezing, or by touching contaminated surfaces and then touching mucosal membranes.. Patients with RSV are contagious for 3-8 days; however, patients who have weakened immune systems can be contagious up to 4 weeks!

Much like seasonal influenza, RSV also has a season, beginning between mid-September/mid-November (depending on the area of the country) and peaking around mid-December/late-February.

Thankfully, RSV is self-limiting and usually resolves in a week or two on its own. But that’s not always the case, and patients who have severe symptoms may require hospitalization. These inpatients receive fluids, directed symptom management, and possibly ribavirin in the most severe cases (e.g., immunosuppressed patients). Dosing for this therapy varies as it’s an off-label use, varying from 10-20 mg/kg/day divided into three times daily dosing with an unclear duration (roughly 7-10 days), and use is very limited due to concerns for carcinogenicity and mutagenicity.

But given these aren’t the majority of cases, we can largely focus on outpatient symptom management after the child has been evaluated by their pediatrician. We don’t necessarily need to treat the pathogen in this case, but managing fever and pain with over the counter medications can be very helpful for the patient’s comfort (as well as the parents’)! Recommendations to the pediatrician for symptomatic management could include the following:

There is another medication associated with RSV, but this one is for prevention: palivizumab (Synagis). This is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against RSV’s F (fusion) protein, which is integral to the virus’s pathogenic cycle. There are specific recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics for which patients should receive palivizumab prophylaxis, so pay special attention to the criteria. It’s not for everyone!

Kawasaki Disease

CRASH & Burn! Kawasaki Disease is mainly a diagnosis of exclusion. It is characterized by inflammation of the blood vessels, mainly the coronary arteries. The cause of this is largely unknown, but it is not contagious. Due to the severe nature of this disease, it’s important to diagnose and treat patients ASAP. (Ok, this is titled as a post on pediatric infection diseases, and then we’re throwing in inflammatory, non-contagious Kawasaki… but this syndrome can often look like an infection, so we’re still deeming it to be relevant!)

I said, “CRASH & Burn” earlier but didn’t quite explain it... But here it goes! It’s a great mnemonic for the signs and symptoms of Kawasaki Disease:

C: conjunctiva or the whites of the eyes turn red

R: rash, mainly affecting the trunk and extremities

A: adenitis, meaning the lymph nodes are inflamed

S: strawberry tongue (classic sign); lips might also be cracked and the child’s mucosal membranes may be red

H: hands (+/- feet) may swell

Burn: fever for > 5 days

Now that we know the signs of Kawasaki Disease, let's discuss diagnosis. As mentioned earlier, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, so what else is on the differential? Viral infections, such as measles, adenovirus, and enterovirus, could cause some of the above symptoms. In addition to viral infections, scarlet fever and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome could also be considerations.

But if none of those diagnoses pan out and the child is deemed to have Kawasaki, then we should start visiting some goals of therapy. First thing’s first - treatment regimens should aim to prevent aneurysms and cardiac complications.

Therapy regimens for Kawasaki’s can become complicated, but are usually based on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin. (Well that’s confusing… I thought we weren’t supposed to use aspirin in children due to risk of Reye’s! In the case of Kawasaki’s, the benefits outweigh the risks.)

IVIG is a blood product, meaning it is actually made from donated blood samples. Replacing immunoglobulin in these patients helps to decrease inflammation (by as yet unclear mechanisms), thereby reducing the incidence of coronary artery abnormalities. Dosing for IVIG depends on the patient’s condition, but in general, it is recommended by the American Heart Association to give a single infusion of 2 grams/kg administered over 10-12 hours (breaking it into smaller doses is not ideal), optimally within the first 5-10 days of illness.

Caveat, there are MANY different IVIG formulations available. So the choice for your patient will depend at least in part on the hospital formulary, but check out this nice chart from the Immune Deficiency Foundation. It goes into better detail about each product, which may help you to make recommendations for specific patients. Considerations may include your patient’s blood glucose or even sodium/fluid balance status.

IVIG comes with its own risks, such as hemolytic anemia, possibility of blood-borne disease transmission since this is a human blood product, and renal complications. In addition, the infusion is time consuming and can cause infusion-related reactions, including flushing, headache, fever, malaise, and chills.

Now, that’s IVIG, but what about aspirin?

Aspirin for Kawasaki Disease is dosed as 30-50 mg/kg/day divided in q6h doses for initial anti-inflammatory properties. Once the patient is afebrile, the dose may be reduced to 3-5 mg/kg/day for 6-8 weeks. These IVIG and aspirin therapies are mostly for normal risk patients, but what about high-risk or refractory patients?

Patients who are considered high-risk include those with repeated episodes of Kawasaki’s, age less than 6 months old, positive ECHO at diagnosis, and presentation in a shock-like state. A Kawasaki Shock Syndrome patient would present with shock (i.e., hypotension potentially affecting organ perfusion), very high C-reactive protein or CRP (>8-10 mg/dL), hyponatremia (≤ 133 mmol/L), low albumin (<3 g/dL), and myocardial dysfunction.

In patients with high-risk of non-response, additional therapies could include corticosteroids or even infliximab. Dosing for corticosteroids varies depending on potency, but we can at least check out sample doses using prednisolone. Prednisolone doses are 2 mg/kg/day (MAX: 60 mg/day) divided into twice daily doses. This should be continued until the CRP normalizes. Once that occurs, a taper is required.

Now, what is this infliximab that I mentioned? Infliximab is a TNF-alpha (tumor necrosis factor) inhibitor that can help reduce inflammatory markers, reduce fever duration, and may decrease risk of cardiac complications in Kawasaki Disease. Infliximab is dosed at 5 mg/kg once and is administered over 2 hours. This medication has its own risks, such as liver dysfunction, drug reactions, antibody development, and increased risk of infections.

Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections

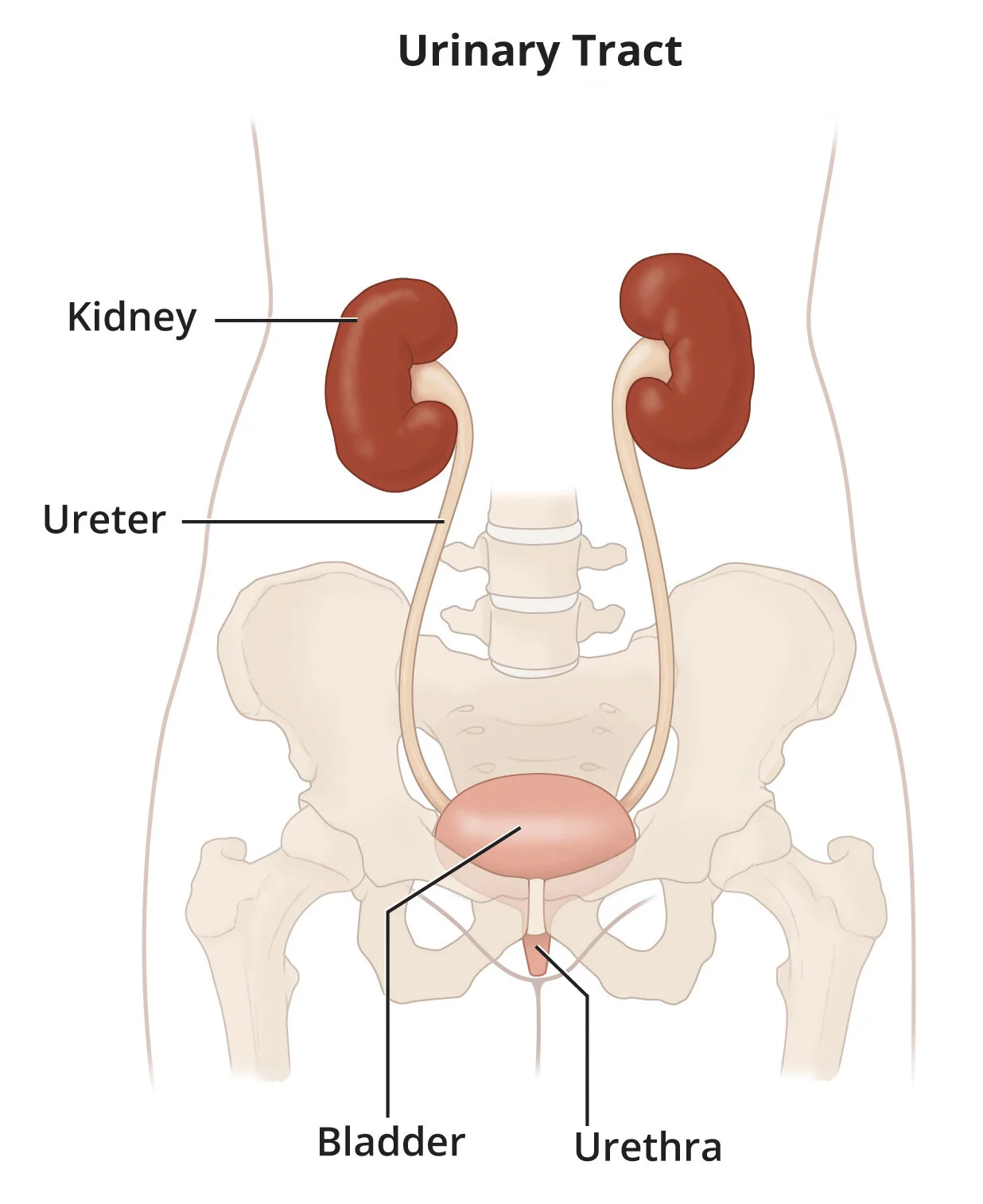

Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) can affect everyone - the young, the old, and anyone in between. Managing these infections even in very young patients and trying to prevent recurrence is important since UTI can place children at risk for kidney damage later in life. Before getting into the treatment, let's review how these infections occur. Bacteria enter the urinary tract and travel up into the bladder. There is also a risk of those sneaky, migratory bacteria traveling out of the bladder, up the ureters, and into the kidneys, leading to pyelonephritis (which won’t be our focus today).

(Image)

Females do have a higher risk of UTI due to the shorter length of the urethra compared to males. One exception to this gender generalization is that uncircumcised male neonates have a higher incidence of UTI than female neonates. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, other risk factors for UTI include structural or functional abnormalities such as vesicoureteral reflux or neurogenic bladder, fever ≥ 2 days, temperature ≥ 39C, < 12 months in age for females, and < 6 months in age for males. Vesicoureteral reflux is when the urine is able to travel back up the ureter from the bladder. Normally, urine will only travel one way, but in these patients, the dual direction flow can increase a chance of infection. As for urinary obstructions, blockages can lead to abnormal flow or prevention of outflow.

Symptoms of UTIs might be difficult to discern in young children if they are unable to tell you how they feel. Some symptoms of UTI are pain, burning, or stinging when urinating, frequent urination, foul-smelling urine, fever, and even pain in the lower back. But how do you know if the patient is incontinent due to normal pediatric development versus secondary to infection? Accidents are accidents, and it can be hard to be sure sometimes! But taking into account other signs or symptoms can help.

Once the child is toilet trained, it will also be a bit easier to figure out if it’s truly a UTI versus just having accidents. So some of the risk factors and considerations change at that point. For those that are toilet trained, patients with a history of a UTI and prolonged fever ≥ 5 days are at higher risk for recurrent UTIs.

Now that we have this background, let’s get into the good stuff… treatment!

For outpatient treatment, cephalexin 50-100 mg/kg/day given by mouth in 3 divided doses is a good start (max daily dose of 4 grams). If there is concern for a more serious infection, the dosing range is slightly higher at 75-100 mg/kg/day by mouth divided every 6 hours. But wait, what about in the case of a penicillin (PCN) allergy?!

If the child has an infamous true PCN allergy, another option is sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX/TMP; Bactrim or Septra) 8 mg of trimethoprim/kg/day by mouth divided in twice daily doses. WARNING: Patients less than 2 months of age can’t receive SMX/TMP due to the risk of kernicterus. And we want to keep in mind the duration of therapy which is 7-14 days.

Did you guys catch that the recommended dosing references mg of TMP/kg/day? If so, good job! TMP is trimethoprim, and it’s the component of SMX/TMP that we use to dose this medication. Let’s do a quick example.

You have a 25 kg patient who has been prescribed SMX/TMP for a UTI. Based on the above recommended dosing of 8 mg of TMP/kg/day, the total daily dose of TMP is 200mg for this patient. Divide that into the recommended twice daily dosing, which means we need to administer 100mg of TMP twice daily. The most commonly available SMX/TMP formulation for pediatrics is the suspension, which contains 200 mg SMX + 40 mg TMP per 5 mL. So if we want a dose of 100mg TMP per dose, that means we need 12.5 mL of suspension to meet that need. Because the sulfamethoxazole to trimethoprim is in a 5:1 ratio, that also means the patient will receive 500mg of sulfamethoxazole per 12.5 mL dose. So the final order will be SMX/TMP 200-40 mg/5 mL suspension, 12.5 mL by mouth twice daily, which provides 500 mg SMX + 100 mg TMP per dose.

For patients who require inpatient management, usually we look to our IV antibiotics for UTI management. Empiric therapy for our youngest (neonates < 28 days old) would be combination therapy with ampicillin 100-200 mg/kg/day IV and gentamicin 4-5 mg/kg/day IV. For those that are 2-24 months, ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg every 24 hours (max daily dose of 1 gram) is recommended. For those ≥ 24 months, the maximum daily dose limit increases to 2 grams/day, although the weight-based dosing is the same (50 mg/kg/day). As the patients improve, become afebrile, begin to tolerate adequate oral intake and therefore oral medications. they may transition to oral therapy and be discharged to finish the remainder of their treatment course.

In Summary…

Well, wasn’t that a lot of information? Don’t worry, there are plenty of good resources available if you need additional information or want to read even more! Some good resources include the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s clinical pathways, American Academy of Pediatrics, Neofax (a part of Micromedex), and Lexicomp. There is even a book of pediatric injectable drugs, called the Teddy Bear Book. Remember, when in doubt, look it up! Or ask your friendly pediatric pharmacist! :)

^^Goals for all of our pediatric patients. Healthy and happy!

And since it’s 2020 and we’re all stuck in our bubbles currently, the other goal here is hopefully playing together again! (Image)