Alcohol Use Disorder

Editor’s Note: The following is another guest post written by this super-awesome P4 duo of previous Epidiolex notoriety. They are students at the University of Texas College Austin of Pharmacy, and beyond that, I'll let them introduce themselves. Thanks to Sammie and Sarah for writing this!

Samantha Le is a P4 student from the University of Texas at Austin College of Pharmacy. Her interests include ambulatory care, academia, transitions of care, and emergency medicine. She hopes to attain a PGY1/PGY2 residency to improve her clinical knowledge and ultimately become board certified. She is interested in pursuing a career in clinical academia, and would love to precept and mentor future pharmacy students!

Sarah Piccuirro is a P4 student from UT Austin College of Pharmacy. When Sarah is not studying, you can find her hanging out with her two dogs and eating all the tacos. After switching gears from the social work field, she become interested in the clinical side of pharmacy after her summer hospital IPPE experience. She hopes to obtain a PGY1/PGY2 residency and is interested in specializing in ambulatory care, critical care, or psychiatric pharmacy.

What your Neuropsych professor sees when she looks up at her audience after her AUD lecture. (Image)

Welcome back to another tldr; guest post! Today we will be focusing on alcohol use disorder. The act of regular, excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages is portrayed in movies and shows as “normal” behavior. Think about it--when was the last time you saw a character drinking way too much on a TV show? Although alcohol use disorder (AUD) and acute alcohol withdrawal may have been brought up in your classes, many of us may feel lost when it comes to managing and treating this disorder from a chronic perspective. If you’re feeling slightly overwhelmed by this point--have no fear, tl;dr is here.

Alcohol Use Disorder Background

AUD is costly, deadly, and an all around bummer. It is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as “compulsive alcohol use [and] loss of control over alcohol intake.” Unfortunately, the CDC estimates that around 4% (about 16 million) of the United States population is affected by alcohol dependence.

In terms of demographics, alcohol dependence affects the majority of low-income males aged 18 to 24 years old. Conversely, binge-drinking has been found to affect high-income individuals aged 18-24 years old, and it impacts roughly 5% of United States citizens.

As far as expenses, excessive alcohol consumption in 2010 was estimated at roughly $249 billion, or approximately $2.05 per drink. Another way to think about it is this: for every $12 mojito purchased at a trendy downtown bar, America spent $2 in healthcare costs.

Excessive drinking is responsible for 1 in 10 deaths among working-age adults around 20 to 64 years old, and alcohol consumption is causally linked to 60 different diseases affecting most, if not all, of our body systems. Yowsers!

The major causes of premature death are injury, alcoholic liver disease, heart disease and stroke, cancers, and gastrointestinal disease.

Pathophysiology of Alcohol

How exactly does alcohol dependence develop?

It’s a fairly complicated process that involves various receptors, neurotransmitters, and behaviors, but we will do our best to summarize.

In order to understand alcohol dependence, it’s helpful to have an understanding of the neurochemistry of intoxication and addiction.

To get started, here’s a crash course on the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate.

If we think of the brain as a car, GABA, which works on GABA receptors, would be the brakes. Glutamate, which activates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, would be the gas pedal. Just like speeding up and slowing down while driving a car, these neurotransmitters work to maintain an excitatory-inhibitory balance in our central nervous system.

Alcohol stimulates release of dopamine from cells in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which is involved in behavioral motivation and reward. Acute alcohol ingestion also inhibits NMDA glutamate receptors and enhances the activity of GABA receptors, producing an overall inhibitory effect on neurons.

At low levels, this can lead to good feelings and relaxation. At high levels, the results can be lethal. If we go back to the car analogy, if we’re constantly pumping the brakes, we’ll get nowhere fast.

Now, as you may know, alcohol can make you pretty sleepy. You may find yourself asking, how can someone possibly function under the chronic influence of alcohol? Well, the human body is an amazing thing.

Alcohol neuroadaptation and reward: a visual representation. The image above demonstrates the complex physiology of neurons and neurotransmitters in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens and the acute effects of alcohol on the reward pathway. Alcohol (as shown by beer/wine) enhances the effects of GABA and opioid receptors while blunting the effects NMDA receptors.

(Image from Connor et al. The Lancet. 2016.)

Chronic alcohol consumption results in the up-regulation of excitatory NMDA receptors to overcome the sedative effects of the potentiated GABA-ergic system and maintain that inhibitory-excitatory balance.

This allows our central nervous system to function more normally in a depressed state.

Patients with AUD will present with varying levels of alcohol tolerance.

To them, a handle of vodka and case of beer may be classified as a normal, daily activity because their bodies’ receptors have altered to compensate.

Acquired tolerance results when repeated use of alcohol contributes to the need for more drinks to produce the same effects. After 1 to 2 weeks of daily drinking, metabolic tolerance can be seen with up to 30% increases in the rate of hepatic ethanol metabolism. Cellular tolerance develops through the neurochemical mechanism of upregulated NMDA receptors described above.

Additionally, individuals learn to adapt their behavior so that they can function better than expected under the influence of the drug. The desire to relieve the anxiety and negative sensations of withdrawal can contribute to relapse and lead to the repetitive and compulsive behaviors that characterize alcohol dependence.

Let’s take a step back and look at the big picture:

A. In a normal state without alcohol, neuronal excitability and inhibition are in balance with NMDA and GABA receptors, respectively.

B. With acute alcohol intake, there’s an overall inhibitory state from alcohol’s agonism of GABA receptors. The NMDAs are overpowered, and inhibition wins. This is the deep sleep after your friend’s bachelorette party.

C. With chronic alcohol use, NMDA receptors are up-regulated to compensate for alcohol’s inhibitory effects on GABA. This increased number and function of NMDA receptors is why people who chronically use alcohol are able to function (at least to some degree). Of note, chronic alcohol also decreases the functionality of GABA receptors.

D. When alcohol is removed in a chronic user and it is no longer agonizing the inhibitory GABA receptors, the up-regulated NMDA receptors are left unopposed and as excitable as they want to be. If you’re not yet tired of the car comparison, we could say withdrawal is like pushing the pedal to the metal (all NMDA) with a severed brake line (no GABA).

Abrupt cessation of alcohol results in a net brain hyper-excitability. This often manifests clinically as anxiety, irritability, agitation, and tremors. These more minor symptoms of withdrawal may even occur while a patient still has a measurable blood alcohol level.

Severe withdrawal can emerge as seizures and delirium tremens (DT), which is characterized by altered mental status and sympathetic overdrive. DT can even progress to cardiovascular collapse and death. Withdrawal seizures and DT occur approximately 2 to 5 days after the last ingestion of alcohol.

We won’t be discussing treatment options for acute withdrawal in this article, but just remember this: benzodiazepines! (And maybe barbiturates.) But that’s another post, TBD.

It is worth nothing that DT is a medical emergency with a mortality rate of 1 to 5 percent. Eeek! The stakes are high, which is why treating AUD properly is so important.

Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder

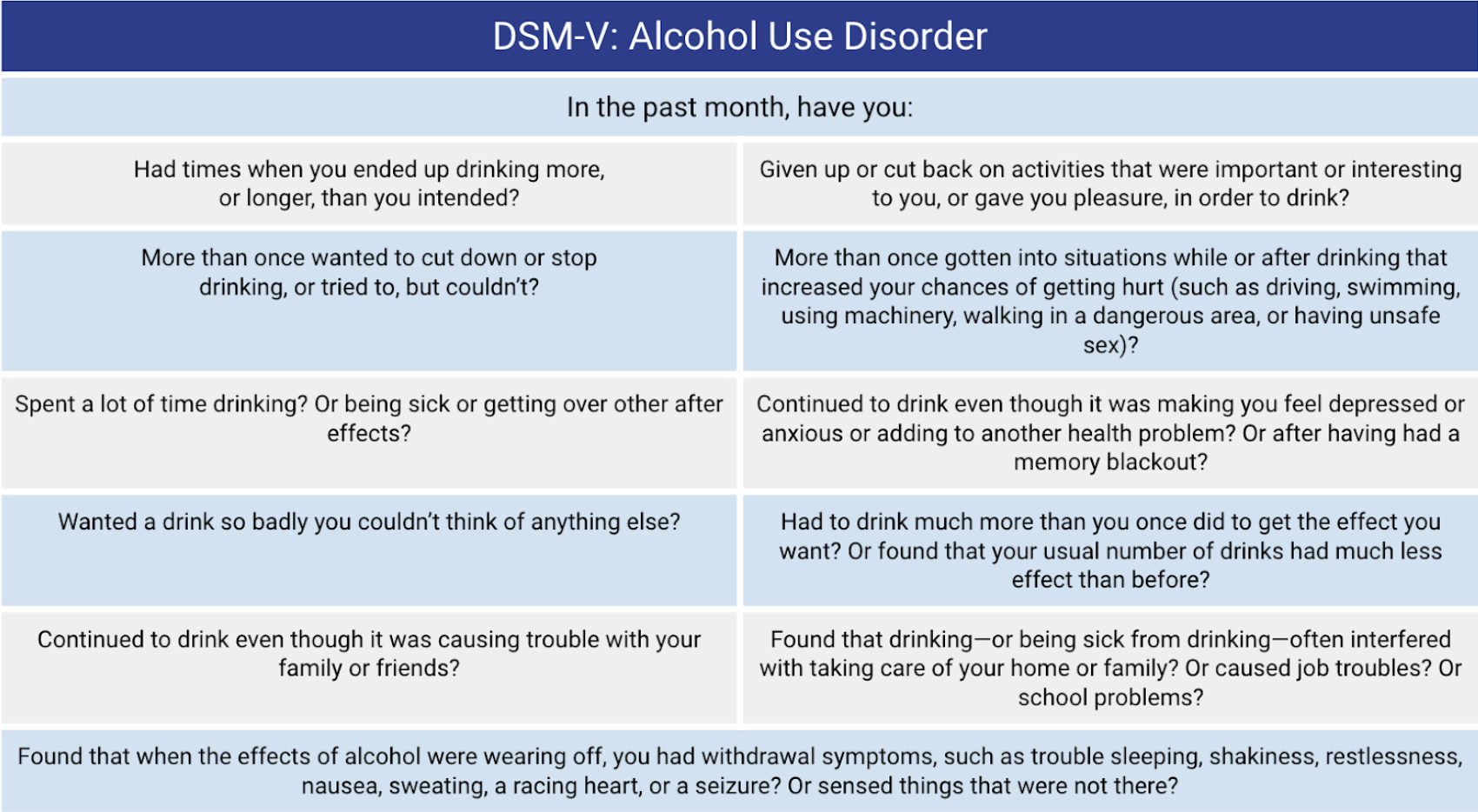

The diagnosis of AUD is pretty cut and dry and is based on criteria set in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-V).

To diagnose AUD, at least two of 11 symptoms below need to be present, and the severity is assessed by the number of symptoms. Mild severity is indicated by the presence of 2-3 symptoms, moderate 4 to 5, and severe 6 or more.

Key points include wanting to cut down but being unable, drinking more to get the same effect, interference with daily life activities, and withdrawal symptoms.

The criterion “Wanted a drink so badly you couldn’t think of anything else?” is designed to measure cravings, which are an addiction-defining characteristic.

So how do we help these patients change their lives?

Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

Unsurprisingly, similar to other disease states, nonpharmacological therapy is the first-line treatment for AUD. This includes treatment planning and providing educational material on harm reduction and risks of alcohol use.

Here’s a handy dandy flow chart that we made all by ourselves illustrating the general treatment approaches in alcohol use disorder as outlined by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

As we mentioned above, we are not covering medications for management of acute alcohol withdrawal, only agents indicated for prevention of relapse in individuals who desire to quit drinking.

Oddly enough, pharmacotherapy recommendations vary depending on what guideline you reference.

The APA guidelines recommend either naltrexone or acamprosate for patients with moderate or severe AUD, who either prefer pharmacotherapy or have not responded to nonpharmacological treatments. Third-line options include disulfiram, topiramate, and gabapentin.

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend baclofen to prevent alcohol relapse in patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

Fun fact - ACG actually gives a solid shout out to pharmacists and suggests that the medical treatment of ALD should be ideally performed by multidisciplinary teams.

We’ve provided a quick review of the recommended first-line agents below:

Drug Name |

MOA |

Dose |

Clinical Pearls |

| Naltrexone | Opioid receptor antagonist which blocks the pleasant and reinforcing effects of alcohol | 50 to 100 mg by mouth daily | - Not recommended in hepatic insufficiency

- Contraindicated in patients taking opioids |

| Acamprosate | Unknown; may stimulate inhibitory GABA-ergic neurotransmission and support ability to remain abstinent from alcohol | 666 mg by mouth three times daily | Not recommended in CrCl ≤ 30 mL/min |

| Baclofen | Unknown; may be mediated by GABA-B receptor stimulation leading to decreased excitatory input into alpha-motor neurons | 5 mg by mouth three times daily; titrate as tolerated to 15 mg by mouth three times daily | - The only medication for AUD studied in alcoholic liver disease

- Renal adjustment - Abrupt discontinuation may precipitate seizures |

Interestingly, gabapentin and topiramate are widely used in clinical practice instead of these first-line agents in many situations. This may be due to a variety of factors including cost, ease of access, and prescriber familiarity.

Gabapentin is primarily used for neuropathic pain and seizures and is extremely popular as it was widely considered to have low abuse potential. However, as recent studies suggest, gabapentinoid abuse has significantly increased due to the opioid epidemic. As such, we may see a decline in prescription and utilization within the next several years.

Topiramate is used to treat epilepsy and seizures, and it may have neuroprotective effects. Topiramate can be initiated while the patient is still drinking, and hypothetically may help alcohol-dependent patients withdraw slowly from chronic alcohol use.

Although these medications are not recommended by guidelines as first-line therapy, they may be considered useful in patients who have other co-morbidities or psychiatric disorders.

Alcohol Use Disorder Literature Review

There are quite a few controlled trials involving naltrexone and acamprosate in AUD and significantly fewer with baclofen. For the sake of brevity, we’ll take a look at some meta-analyses of the first line pharmacotherapy options.

A 2014 meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate included 122 RCTs and 1 cohort study with a total of 22,803 participants. Most of the trials included in the analysis assessed naltrexone, acamprosate, or both.

The primary endpoints were return to any drinking and return to heavy drinking. Heavy drinking was not uniformly defined across the studies included. However, it was frequently classified as 5 or more standard drinks per day for men and 4 or more standard drinks per day for women, which aligns with the definition provided by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Both acamprosate and oral naltrexone were associated with reduction in return to drinking. Only oral naltrexone was associated with improvement in return to heavy drinking with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12.

No information was provided regarding baseline characteristics, but individuals with elevated liver enzymes were generally excluded from naltrexone and acamprosate studies. It is worth noting that many of the studies included in the meta-analysis incorporated medical management in addition to pharmacotherapy, which could skew results.

A 2018 meta-analysis of baclofen for AUD included 12 RCTs with a total number of 590 participants. The trials compared baclofen to either placebo or another agent, and most trials used a dose of 30 mg/day in divided doses.

The trials examined abstinence days, heavy drinking days, and abstinence rates. They also looked at psychological outcomes such as cravings, depression, and anxiety.

This meta-analysis showed that baclofen had a significantly improved abstinence rate when assessing intention to treat with an odds ratio of 2.67 and a NNT of 8.

Unlike trials with naltrexone and acamprosate, baclofen trials did not exclude individuals with hepatic insufficiency. In fact, some trials specifically looked at baclofen use in individuals with alcoholic liver disease. This is important to note since many individuals with AUD may also present with hepatic disease.

Treatment Considerations for Alcohol Use Disorder

How most of us feel when trying to manage AUD. (Image)

Pharmacotherapy for AUD is not as simple as the nifty chart above makes it seem.

The AUD practice guidelines leave many questions unanswered.

Is it ok to initiate medication during acute withdrawal?

What is the duration of therapy?

What is the stance of community organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous?

There are no definitive answers to these questions, but we’ll try to provide as much clarity as we can.

When to initiate therapy

Many patients present to the ER for alcohol detoxification, or they may present for a different reason and alcohol dependence is discovered during assessment. Regardless, admission to a hospital for acute alcohol withdrawal is not a rare situation by any means.

Although the FDA labeling recommends that treatment with naltrexone not begin until signs and symptoms of acute alcohol withdrawal have subsided, alcohol use is not a contraindication to naltrexone.

According to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) guidelines, it is safe for patients to begin taking naltrexone or acamprosate during medically supervised withdrawal or if they are actively drinking.

There is less guidance available for baclofen use in the acute withdrawal phase of AUD, but there are studies that specifically examine its use for reducing withdrawal symptoms during the acute period.

Based on the current literature available, it is reasonable to consider that baclofen may be safe to initiate during acute withdrawal, but consideration for additive effects with concomitant medications such as lorazepam, phenobarbital, or chlordiazepoxide is imperative. These decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Duration of treatment

Another gray area with no clear guideline is the optimal length of treatment. According to the Medication for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Brief Guide by SAMHSA, patients should have ongoing monitoring of adherence to treatment, ability to abstain or reduce use, and overall health status.

Based on this information, the provider can decide whether to continue pharmacotherapy. Another article about naltrexone use in alcohol disorder suggests that treatment should last 3 to 4 months in most patients. Naltrexone may be increased to 100 mg/day, and treatment may be continued for patients who are not abstinent at 3 to 4 months.

Stance of Alcoholics Anonymous/Narcotics Anonymous

Both Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) have guides that address the use of medications for substance use disorder.

Although some members have negative attitudes towards medication use in general, the organizations' official statements reflect support of proper medical treatment. In fact, AA explicitly states that members should not “play doctor” and advise others on medication provided by legitimate, informed medical practitioners or treatment programs.

NA, in particular, seems to be more outspoken as far as medically assisted treatment. However, it appears that this is generally in regards to methadone and Suboxone.

NA suggests that "practitioners and physicians who prescribe medications to treat addiction may want to seek out an NA member contact in their community to assist them with locating meetings that may be more friendly to people receiving medication-assisted treatment."

Conclusion

If you’ve made it to this point, wow, 10/10. Hopefully you feel a little bit better about management and treatment of AUD. The biggest takeaway points are summarized below:

AUD is a costly disease associated with significant disease burden and premature death.

AUD develops through mechanisms of neuroadaptation, reward pathways, and tolerance development.

It is classified using DSM-V criteria as mild (2-3 symptoms), moderate (4-5 symptoms), or severe (> 6 symptoms).

For patients with moderate to severe AUD who are willing to quit drinking, naltrexone, acamprosate, and baclofen are recommended as first-line pharmacologic agents.

Medications should be selected based on patient-specific factors, preferences, and comorbidities.

Thanks for sticking it out with us, we hope this helps!