A Primer on Hereditary Angioedema

Editor’s Note: In a world where it can be hard to find people willing to reach into the unknown, tl;dr is lucky enough to have Sammie and Sarah, the amazing P4 duo of previous Epidiolex and Alcohol Use Disorder fame. They could rest on some laurels with those 2 posts alone and no one would blame them, but no, they keep stretching to learn more AND share their findings with you. Not to mention on a heck of a topic!

Sammie and Sarah are students at the University of Texas College Austin of Pharmacy (for at least a smidge longer), and beyond that, I'll let them introduce themselves. Huge kudos to Sammie and Sarah for writing this!

Samantha Le is a P4 student from the University of Texas at Austin College of Pharmacy. Her interests include primary care, academia, and emergency medicine. She is interested in pursuing a career in emergency medicine and would love to precept and mentor future students!

Sarah Piccuirro is a P4 student from UT Austin College of Pharmacy. When Sarah is not studying, you can find her hanging out with her two dogs and eating all the tacos. After switching gears from the social work field, she become interested in the clinical side of pharmacy after her summer hospital IPPE experience. She hopes to obtain a PGY1/PGY2 residency and is interested in specializing in ambulatory care, critical care, or psychiatric pharmacy.

One example of facial angioedema progression. (Image)

Welcome back to another tldr; guest post! Our topic today is hereditary angioedema.

Huh? Hereditary angioedema??? Yes, we wrote that correctly.

Introduction

At a 100,000 foot view, angioedema is defined as subcutaneous or submucosal swelling that is non-pitting when pressure is applied. Around 25% of people will experience an acute attack within their lifetime. These attacks may be severe and even life-threatening due to upper airway involvement and respiratory compromise.

So, how many types of angioedema exist?

When we think of angioedema, two scenarios typically come to mind:

patients who are severely allergic to bee stings, peanuts, eggs, etc., and

patients who present with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-associated angioedema.

Now let’s take a look at Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 (courtesy of Sarah and Sammie’s tech skills)

Wait, now you’re saying there are FOUR types?!?!

According to the literature, angioedema is classified into four distinct groups.

Histamine-mediated angioedema is classified as a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. Allergen exposure induces immunoglobulin E (IgE) binding to mast cells and causes mast cells to degranulate, or break. This process increases histamine release, which contributes to bronchial smooth muscle constriction and vasodilation.

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema is further divided into three subtypes: hereditary (Types I, II, III), acquired, and ACE inhibitor-associated. Like the name suggests, this type of angioedema is affected by increased bradykinin levels.

We’ll get to hereditary angioedema (HAE) soon, but in the meantime, here are some fun facts about the other bradykinin-mediated types:

Acquired angioedema is extremely rare and affects around 1:100,000 to 1:500,000 people, and it presents around the 5th decade of life.

Conversely, ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema may affect patients at any age and any dose--even if patients were previously asymptomatic!

(FYI, one 2008 meta-analysis estimated that as many as 10% of patients will experience cross-sensitivity reactions from angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and ACE inhibitors, although subsequent studies have since postulated lower percentages. If an ARB is chosen after a careful examination of risk and benefits and discussion with the patient, it is extremely important to counsel patients on recognizing signs and symptoms and to seek help immediately.)

Idiopathic angioedema is typically a diagnosis of exclusion. It is thought to be mast-cell mediated, pruritic (itchy), and associated with chronic spontaneous hives.

Pseudoallergic angioedema is extremely rare, and limited data and treatment recommendations exist regarding this subtype.

Figures A and B provide us with a great explanation of histamine-mediated vs bradykinin-mediated angioedema.

Figure A: Pathway for histamine-mediated angioedema. Exposure to prior or known allergen induces immunoglobulin E (IgE) binding to mast cells, subsequent mast cell degranulation, and release of histamine.

Figure B: Pathway for bradykinin-mediated angioedema. C1 esterase inhibitor moderates enzymes within the proteolytic kallin-kallikrein cascade, including factor XII and kallikrein, and functions as an inhibitory checkpoint for complement system activation. Decreased C-1 esterase inhibitor levels lead to increased kallikrein activation and conversion of kininogen to bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to B2 receptors and causes increases endothelial permeability and vasodilation, leading to observed angioedema symptoms.

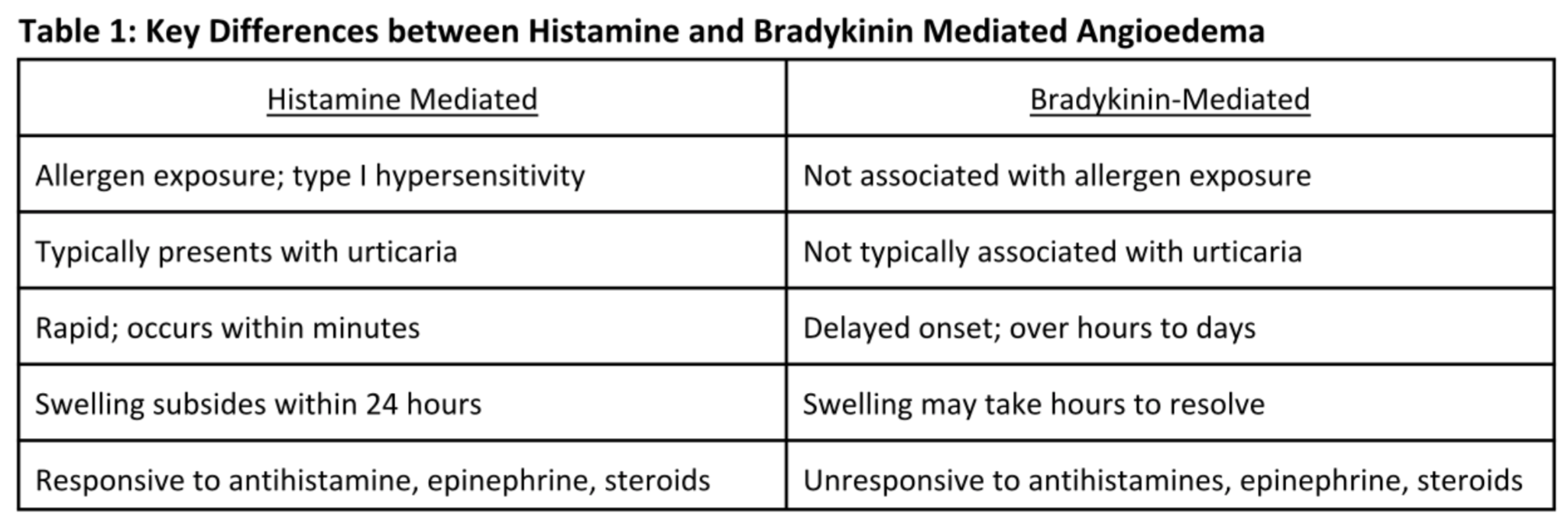

Again, it is important to understand that histamine-mediated and bradykinin-mediated angioedema are two distinct disease states. Key differences are listed below in Table 1, and include: differing clinical presentations, pathophysiologies, and time to symptom onset and reduction. Most importantly, bradykinin-mediated angioedema will not respond to antihistamines, epinephrine, or steroids.

So now that we’ve got the satellite view covered, let’s zoom in a little…

Hereditary Angioedema: Background

#TBT autosomal dominant inheritance pattern from freshman bio. Because #Mendel. (Image)

Oh, well, not zooming too much yet. Still need to get a handle on what this mysterious hereditary type is!

At a 50,000 foot view, hereditary angioedema (HAE) is an extremely rare, autosomal dominant disorder that affects around 1 in 50,000 people. This means that only one parent needs to carry the gene for the child to express symptoms of the disease, but it’s still only a 50% chance the child will inherit the gene.

However, 25% of HAE attacks may occur spontaneously through a de novo mutation.

HAE attacks can be characterized as recurrent episodes of angioedema that affect the skin, upper airway, and gastrointestinal mucosa. Again, these attacks are NOT resolved with epinephrine, steroids, or antihistamines.

HAE can be further classified into three different subtypes:

Type 1: affects 85% of HAE patients

Type II: affects 15% of HAE patients

Type III: unknown

Pathophysiology of Hereditary Angioedema

Patients with hereditary angioedema exhibit SERPING1 gene mutations on chromosome 11. To break down that mouthful, this gene codes for synthesis of C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH).

K, not sure that actually broke down anything, so let’s try that again.

Look back up to Figure B above of the bradykinin-mediated pathway for angioedema. Where does C1-INH fit?

One of the normal functions of C1-INH is to inhibit kallikrein, which is the enzyme that cleaves kininogen to make bradykinin. It also normally inhibits factor XII, which in addition to being a clotting factor, also activates pre-kallikrein into kallikrein. If we have decreased or abnormally functioning C1-INH, there can be increased kallikrein activity…which leads to increased bradykinin levels…which leads to angioedema-related symptoms.

Type I: low C1-INH levels and decreased functionality

Type II: normal (or even high) C1-INH levels, but decreased functionality

Type III: normal C1-INH levels

This type was initially believed to be estrogen-dependent because cases were mainly limited to female patients. However, it is now thought to be affected by a mutation in the F12 gene, which codes for coagulation Factor XII.

Signs and Symptoms of Hereditary Angioedema

Prodromes aren’t as cool as Buzz is making them out to be. (Image)

Symptoms are typically nonspecific and include nausea, fatigue, headache, and abdominal pain. Patients may experience a prodromal period (3-4 days prior to the attack).

Lastly, around ⅓ of Type I and Type II patients may present with a non-itchy rash (erythema marginatum), which is not observed in Type III. These symptoms may be triggered by a variety of factors: anxiety, stress, minor injuries, infections, or even hormonal changes.

Pharmacotherapy of Hereditary Angioedema

Now…NOW we get to the nuts and bolts!

Disclaimer: even though Type III HAE shares a lot of characteristics with Types I and II, it’s still this weird, not-well-characterized entity. So the treatments below may have some place in treatment of Type III, but the 2018 guidelines really only address the first 2 types.

Anyways, there are six drug classes used as acute or prophylactic treatment for HAE. Check out this breakdown of the agents:

C1 Esterase Inhibitors (C1-INH)

There are four agents currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

Basically, the idea behind this entire class of medications is to replenish C1-INH levels, which may help to promote bradykinin breakdown.

Berinert and Ruconest are approved for acute treatment, whereas Haegarda and Cinryze are indicated for prophylaxis. All of these are human-sourced C1 esterase inhibitor products except Ruconest, which is the only recombinant product.

So if you’re a patient who suffers from HAE, you’re having a life-threatening attack with shortness of breath from the swelling in your throat… HOW FAST IS THIS GOING TO GO AWAY?!?

Let’s look at Berinert since it’s a likely choice for this scenario. The median onset of symptom relief with Berinert is 15 min, although depending on location of attack (laryngeal versus facial/abdominal), the median onset can be as long as 45 min. It can also take anywhere between 5-8 hours for complete symptom resolution with Berinert. And those are median times, so of course there are outliers. (This is why HAE can be so frightening!)

Some interesting considerations:

Ruconest is from a much nicer bunny than this! (Image)

Acute Treatment

Berinert is dosed at 20 units/kg and is administered intravenously after reconstitution.

Interestingly, the majority of patients reported dysgeusia (distortion of taste) as one of the most common adverse reactions.

Ruconest is the only synthetic/recombinant C1-INH formulation and is dosed according to weight (either less than or greater than 84 kg).

This product is derived from rabbit plasma and is therefore contraindicated in patients with rabbit allergies!

Long-term Prophylaxis

Cinryze is dosed at 500 to 1,000 units (max 2,500 units) intravenously every 3-4 days (~twice weekly).

Haegarda is the only prophylactic inhibitor that is dosed subcutaneously every 3-4 days (~twice weekly).

Of note, an important warning for all C1-INH products is the risk of thrombotic events, especially in people who already have risk factors. (Thrombotic risk factors include things like a history of thrombosis, use of contraceptives, morbid obesity, immobility, atherosclerosis.) Patients with these characteristics should be closely monitored during and after C1-INH therapy!

Firazyr (Icatibant)

Firazyr (icatibant) was approved in 2011 for acute HAE treatment and is dosed 30 mg subcutaneously every 6 hours (max 90 mg within 24 hours). Unlike our other medications, it is a competitive bradykinin antagonist and blocks binding at bradykinin B2 receptors.

Clinical trials showed that icatibant provided a 50% decrease in symptoms within a median of 2 hours; however, 97% of patients reported localized injection site reactions (bruising, burning, swelling). Icatibant is available as a pre-filled syringe and is stable at room temperature, which may be beneficial when considering ease of administration.

Let’s take a slight detour away from HAE into the land of ACE-inhibitor associated angioedema for just a hot second…

There has been interest in use of icatibant for ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema. Currently, it is not approved for this indication due to conflicting data regarding its efficacy. (Remember: although ACE inhibitors demonstrate their therapeutic effects by blocking the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, they also inhibit bradykinin breakdown. The subsequent build up of bradykinin is thought to be associated with both angioedema and that annoying dry, hacking cough.)

So let’s look at the data.

The first study was a randomized controlled 2015 trial conducted in Germany and published in NEJM. Patients were randomized to either standard treatment of antihistamines + steroid (clemastine + prednisolone) or icatibant. The primary endpoint considered was time to complete resolution of edema. Thirty patients were enrolled over a 16 month period from July 2010 to December 2011. Results indicated that the icatibant group experienced more rapid onset of symptom relief (2 hours vs 12 hours) as well as significantly faster time to complete resolution of edema (8 hours vs 27 hours).

Conversely, a 2017 study published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology suggested that icatibant was not efficacious for moderate to severe ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. This was a multinational, multi-center study which spanned 4 countries and 31 centers, and it enrolled a relatively large number patients (N=121). Patients were randomized to either icatibant or placebo approximately 8 hours from symptom onset (so long!!). The primary endpoint was time to discharge after study drug administration, which was similar at ~4 hours in both groups. There was also no difference between groups in time to onset of symptom relief (~2 hours).

At this time, it is reasonable to conclude that icatibant probably isn’t an option for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Which is hard to swallow given the lack of options altogether for this specific type of angioedema! However, further studies would be useful to fully evaluate its place in therapy.

Ok, now back to HAE!

Kallikrein Inhibitors

Kalbitor (ecallantide) and Takhzyro (lanadelumab-flyo) are kallikrein inhibitors. These agents directly block kallikrein and inhibit conversion of high molecular weight kininogen to bradykinin.

(Ok, bear with us. How cool is the name Kalbitor? Don’t y’all just envision some Transformers-like machine fighting kallikrein with the Power Rangers theme song jamming?

Or is it just us…

Anyways.)

Ecallantide is indicated for acute HAE treatment and is dosed at 30 mg subcutaneously over a total of three 10 mg injections for patients at least 12 years old. This has a fairly short half-life and provides symptom relief within 4 hours. Side effects are relatively minor and include headache, nausea, fatigue, and diarrhea.

Lanadelumab came onto the market fairly recently in August 2018 and is indicated for HAE prophylaxis in patients at least 12 years old. This is the first monoclonal antibody and is dosed at 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. The dosing interval may be extended to every 4 weeks if patients are symptom-free for at least six months.

Lanadelumab was well tolerated in clinical trials with minimal adverse effects. Although lanadelumab’s unique dosing may improve patient compliance, it is a relatively new drug. Current costs are unknown, but a 30-day supply is estimated to cost around $45,000 .

Plasma

Plasma has been used for several decades as acute HAE treatment because it is theorized to contain products which facilitate the breakdown of bradykinin. It is dosed as 2 to 4 units intravenously and is available either as fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or solvent detergent-treated plasma (SDP). Because FFP is derived from human plasma, it carries the risk of viral infection, although the risk of this has significantly decreased in the past few decades due to improvements in screening technologies. Conversely, SDP is purified and has been pathogen-deactivated.

Confusingly, there is some concern that FFP may exacerbate the symptoms of angioedema. One case report describes a worsening of facial swelling 30 minutes after receiving FFP; however, it’s worth asking whether this clinical decline was due to the FFP or to the natural course of the angioedema given the lack of directed C1-INH treatment until later in the patient’s emergency department stay.

Regardless, with the emergence of novel drug classes and risk of viral infection/attack exacerbation, plasma has fallen out of favor and is typically not recommended as a first-line agent unless the other treatments are not available.

Androgens

Danazol is an attenuated androgen that has been historically used for HAE prophylaxis. Although a specific mechanism of action is yet to be understood, it has been theorized to increase hepatic C1-INH production. Danazol dosing varies across literature from every other day to 2 to 3 times daily.

Although this is an oral medication, we must consider the long-term side effects of androgens. In the pediatric population, androgens have been linked to:

hypogonadism in males,

virilization in females, and

growth defects.

The side effects of this medication are numerous and also include voice deepening, acne, and anxiety. As danazol is extensively hepatically metabolized and also carries a risk of hepatoxicity, liver enzymes should be monitored. In reality, this has largely fallen out of favor with the development of newer and safer agents.

Tranexamic Acid

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic that is sometimes used off-label for HAE prophylaxis in areas that don’t have access to the newer options.

TXA is thought to bind to plasminogen, thereby decreasing plasmin formation. Plasmin normally contributes to the activation of the complement system via C1 esterase, a process that is regulated in part by our good ol’ friend C1-INH. So by decreasing plasmin formation, TXA is thought to decrease consumption of C1-INH. This then theoretically leaves more C1-INH available to help promote bradykinin breakdown. (Kinda seems like driving to Kansas to get to New York, but mmmkaaaay.)

It is dosed 1,000 mg to 1,500 mg orally 2 to 3 times daily. Conversely, it can be dosed 25 mg/kg/dose 2 to 3 times daily. As this is an antifibrinolytic, it’s important to note the risk of thrombotic events with TXA.

So why don’t we use the much cheaper, orally administered TXA for prophylaxis instead of all the fancy, new, pricey injectables?

Evidence. Or lack thereof, my friends.

One meta-analysis of the use of TXA for prophylaxis tried to boil down the numbers. Not only did the authors conclude that only ~50% of case reports and observational studies showed any sort of benefit, but they also pointed out that one study of HAE attacks indicated longer duration of acute symptoms in patients who had been receiving TXA prophylaxis!

So long story short, there’s questionable efficacy overall AND potentially longer attacks when they do arise.

No bueno.

Why isn’t TXA used for acute treatment? The efficacy of TXA for acute HAE attacks just plain isn’t that fabulous. The FAST-2 trial compared TXA with icatibant in 74 patients with acute HAE attacks with a primary endpoint of median time to clinically significant relief of symptoms. TXA was woefully slower with a median time of 12 hours as compared to icatibant’s 2 hours!

So not exactly drug of choice…

Phew. Let’s take a breather! If you prefer pictures over text, we’ve included two diagrams below which illustrate where our medications work on the bradykinin pathway. The first is fairly simplified to help you get a grasp on the big buckets, and the second is for the slightly crazier people who need details to remember the info. Choose your own adventure on which one works best for you!

The easier version with mostly words and fewer of those confusing complement “C” particles.

For you crazed detail-lovers who need all the complements present. (Image)

Hereditary Angioedema Guideline Recommendations

Before we dive into guideline recommendations, it is important to note that current American guidelines do not exist. The World Allergy Organization (WAO) and European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) published the first set of international HAE guidelines in 2012. These guidelines were later revised and updated in 2018.

Acute Hereditary Angioedema Treatment

Current guidelines recommend C1-INHs (Berinert or Ruconest), Firazyr (icatibant), or Kalbitor (ecallantide) as first-line treatment. Adverse effects are typically mild, and these agents have proven to be efficacious in clinical trials.

Solvent-detergent treated plasma may be considered second line due to the low risk of viral transmission. Lastly, fresh frozen plasma may be considered as an alternative. However, it is important to keep in mind the risks of plasma infusions as well as the possibility of attack exacerbation.

Hereditary Angioedema Prophylaxis

C1-INHs are also indicated as first-line for prophylaxis (Cinryze, Haegarda). Lastly, although Takhzyro has not been implemented in the 2018 revision, it will likely be integrated with future updates due to biweekly dosing and mild adverse effect profile.

Attenuated androgens (danazol) may be considered as an alternative; however, providers must consider the numerous androgenic side effects and varied dosing when starting this agent. Lastly, tranexamic acid is no longer recommended due to lack of efficacy when compared to newer agents.

The guidelines recommend that treatment plans must be individualized for all patients. Additionally, patients should have on-demand treatment available as well as appropriate education on self-administration techniques. Lastly, both Hepatitis A and B vaccinations are recommended to decrease the risk of viral infections.

For your tl;dr needs, we have included a treatment algorithm below!

Hereditary Angioedema Pipeline: What’s Next?

HAE, although rare, has continued to generate marked interest. (As of this post, there are 11 ongoing clinical trials on clinicaltrials.gov.) As far as future outlook, we may see a gradual transition from subcutaneous to oral formulations. Oral formulations would benefit patients who are unable or unwilling to self-administer injections.

As one example, a 2018 NEJM article describes the use of an oral, small molecule kallikrein inhibitor (BCX7353) for HAE prophylaxis. Seventy-seven patients were randomized to once daily dosing of 62.5 mg, 125 mg, 250 mg, and 300 mg over a 28 day period. The findings from this study suggest that patients randomized to doses >125 mg experienced a statistically significant lowering in rate of acute attacks, as well as significantly improved quality of life scores. Additionally, adverse effects were noted to be mild and primarily gastrointestinal in nature.

So there IS some exciting news on the horizon!

Conclusions

Thank you for sticking with us until the very end! We hope that this post sheds some light on a unique and fascinating disease state. We’ve summarized the main takeaways below:

Angioedema encompasses several different subtypes with unique pathophysiologies.

Hereditary angioedema is NOT an allergic reaction and will NOT respond to epinephrine, antihistamines, or steroids.

International guidelines recommend C1-esterase inhibitors as first-line acute and prophylactic treatment.

It is essential for all HAE patients to have on-demand treatment and patient education.