A Clinician’s Guide to Inpatient Electrolyte Replacement

Steph’s Note: This week, we’re returning to the clinical world with a topic that is sadly oft neglected in pharmacy curricula - electrolytes. Even though it seems like these should be a super easy topic (“they’re just basic chemistry, right?”), when you’re faced with the task of figuring out how to manage them, you rapidly realize just how complicated they can be!

To help us navigate the murky electrolyte world, we have Dr. Josef Nissan, critical care pharmacy hero of past tl;dr vasopressor fame (along with HIT, methemoglobinemia, and acetaminophen toxicity posts, just to name a few). He has kindly put his brain on paper for us in an easy-to-follow form, complete with charts that you really may want to consider saving. Just saying. Teach us!

We’ve all been there. You’re rounding with the physician when all of a sudden you're tasked with the responsibility of ordering electrolyte replacement. You just smile, nod, and hope for the best.

Me, staring at the computer trying to figure out which electrolyte supplement to choose. (Image)

If you’re like I used to be, then you may internally be freaking out because you have no idea which electrolyte supplements to choose, how much, which route is preferred, when to recheck levels, and so on.

Early in my pharmacy career, I strongly disliked electrolytes. From my experience, I feel like no one ever taught me the specifics of electrolyte replacement. I was just sort of expected to figure it out on my own. To make matters worse, I rarely ever asked questions about electrolyte replacement because I didn’t want to look “dumb” since there’s this notion of it being an easy topic.

Not quite…

So here I am a few years later writing this post to teach you everything you need to know about electrolytes. Obviously there are a lot of electrolytes, so it would take way too many posts to go over all of them. Keeping that in mind, I’m going to focus on the most common inpatient electrolyte deficiencies including potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and calcium.

(Yes, sodium and chloride are also common electrolyte deviations, but those would require their own special articles since they’re complex and are typically due to underlying diseases. Perhaps more another time…)

How Do Electrolyte Deficiencies Present?

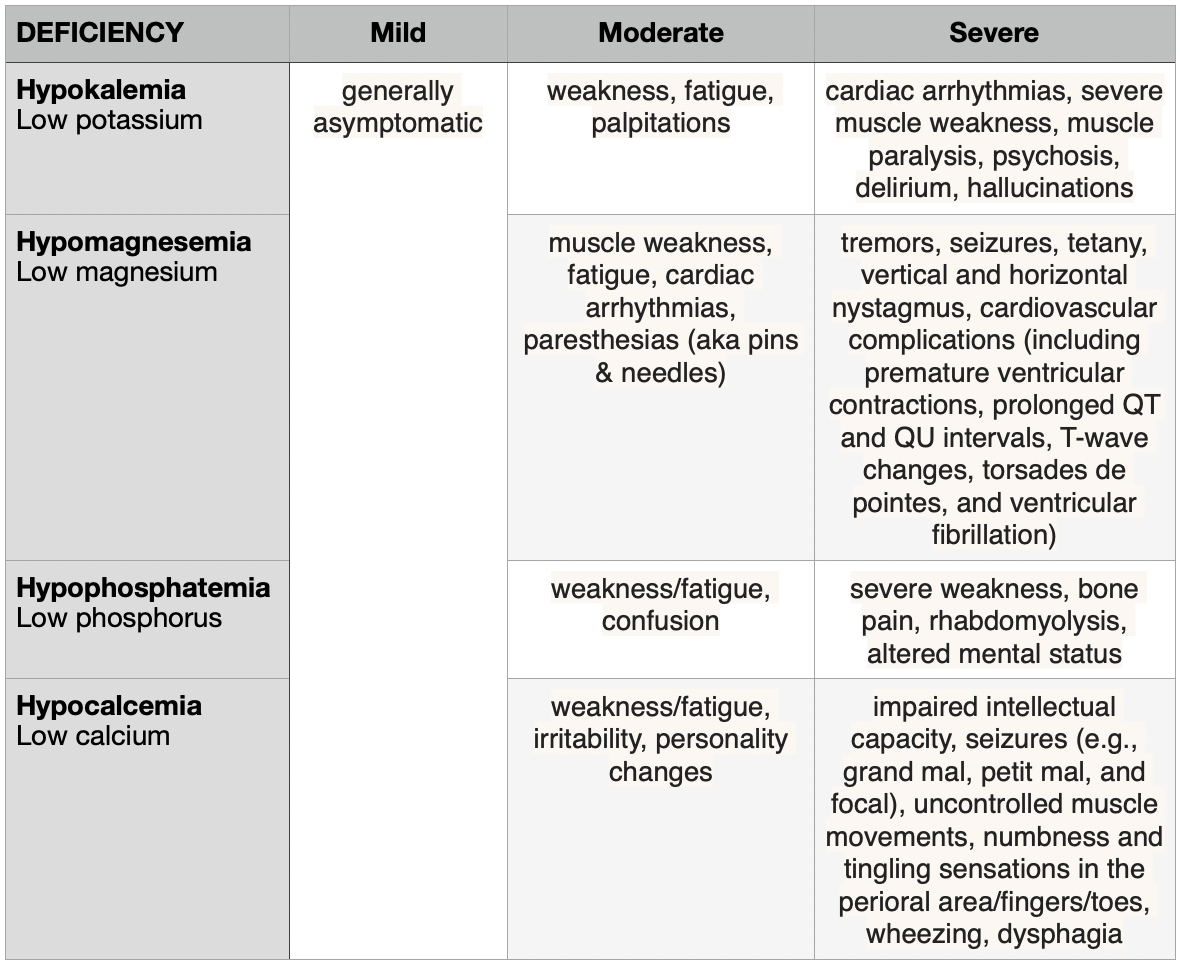

To get a better understanding of the importance of electrolyte replenishment, let’s first focus on the harmful effects associated with electrolyte deficiencies. Don’t underestimate the severity of this topic, or else it could bite you in the booty! Alright, let’s review:

Do you notice the recurrent theme? While generally mild electrolyte deficiencies are pretty benign, moderate/severe abnormalities can cause many life-threatening conditions, including cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, muscle paralysis, and much more.

So please, replace those dang electrolytes.

Before we move on and review electrolyte supplementation, I want to give a small disclaimer. There aren’t specific guidelines that discuss electrolyte replacement. Each institution has slightly different treatment thresholds, products, etc., and don’t even get me started on what happens when one product goes on shortage! Long story short, the details that I discuss may not be an exact replica of your institutional protocol, but they should be pretty darn close.

With that out of the way, let’s dive in.

How to Treat Electrolyte Deficiencies

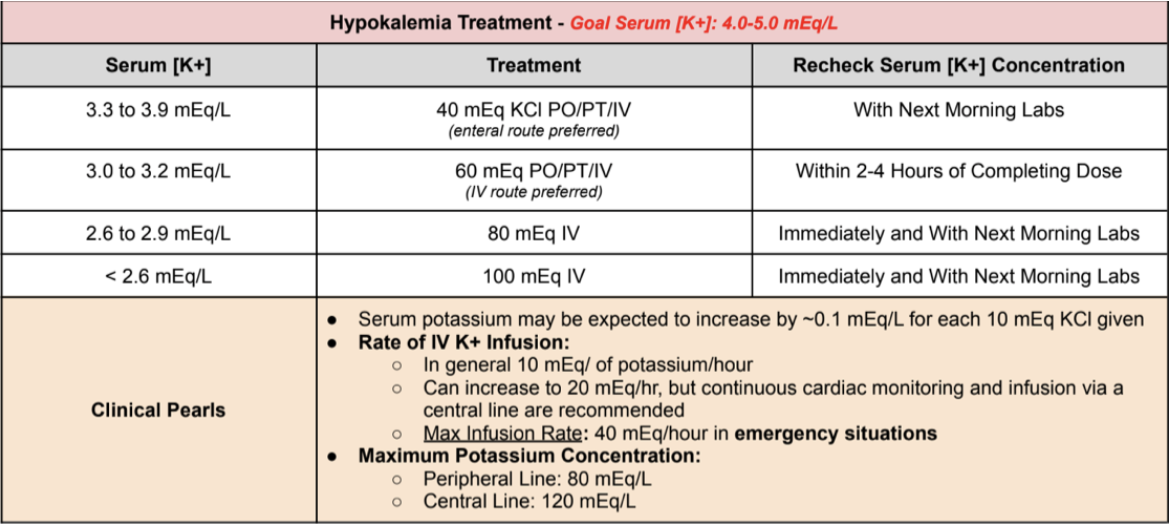

Hypokalemia

This is probably the electrolyte deficiency that you are the most comfortable with. (Yes, I did just call you out. This is tl;dr, so I don’t want to waste brain space with useless filler words. So I’m going to give you the cold hard facts.)

Normal Potassium Levels: 3.6 to 5.2 mEq/L

Hypokalemia classifications

Mild: 3.0 to 3.5 mEq/L

Moderate: 2.5 to 3.0 mEq/L

Severe: < 2.5 mEq/L

Common causes of hypokalemia

Medication-induced: diuretics, insulin, sodium bicarbonate, albuterol

FYI, if these treatments look familiar together when referencing potassium, it’s likely because you’ve learned them as common treatments for hyperkalemia…

Other causes: alcoholism, chronic kidney disease, diabetic ketoacidosis, diarrhea, excessive sweating, vomiting, malnutrition

Common potassium replacement products

1st-line: potassium chloride

2nd-line:

Potassium phosphate: usually reserved for patients with hypokalemia AND hypophosphatemia

Potassium acetate: usually reserved for patients with hypokalemia AND metabolic acidosis (e.g., renal tubular acidosis, diarrhea)

Treatment of Hypokalemia

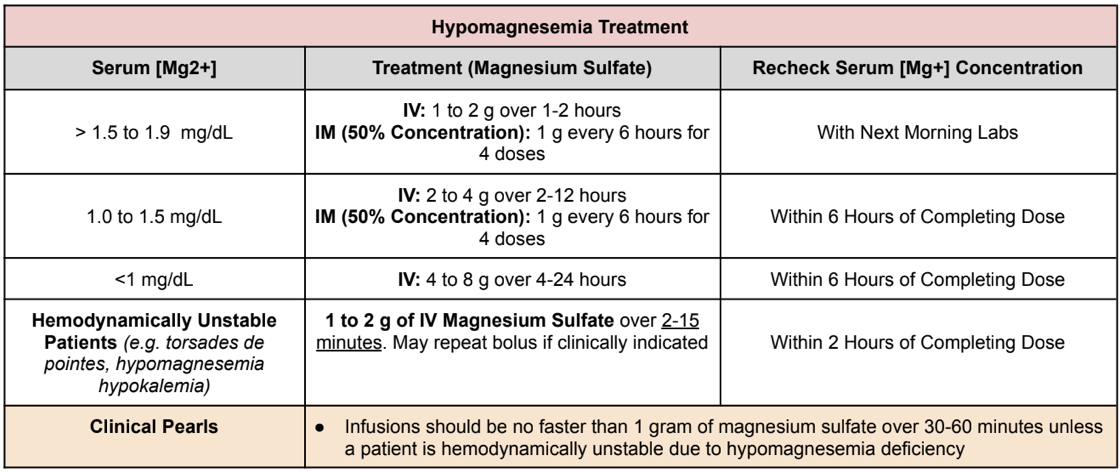

Hypomagnesemia

I feel like magnesium doesn’t get the love and respect that it deserves as an electrolyte…especially considering the fact that 2/4 electrolytes that we are discussing are dependent on magnesium levels.

Mmmhmm, you read that right.

A visualization of the futility you feel when you try to replace potassium without adequate magnesium levels. (Image)

Magnesium helps transport potassium and calcium ions in and out of cells. So a lack of magnesium can lead to low levels of both potassium and calcium. So if you have treatment-resistant hypokalemia, take a look at that magnesium level. In a lot of cases, replacing magnesium can actually correct hypokalemia without having to give tons of potassium supplementation.

Normal Magnesium Levels: 1.7 to 2.5 mg/dL

Hypomagnesemia classifications

Mild: 1.5 to 1.9 mg/dL

Moderate: 1.0 to 1.5 mg/dL

Severe: < 1.0 mg/dL

Common causes of hypomagnesemia

Gastrointestinal: malnutrition, chronic vomiting, severe diarrhea

Medication-induced: diuretics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, cisplatin, pentamide, digoxin, calcineurin inhibitors

Other causes: alcoholism, uncontrolled diabetes insipidus, hypercalcemia, Familial Renal Magnesium Wasting

Common magnesium replacement products

1st-line: magnesium sulfate (IV)

2nd-line: elemental magnesium (PO) (e.g., magnesium oxide) or milk of magnesia /magnesium hydroxide (PO) may be initiated for less severe cases. However, oral magnesium is poorly absorbed, and diarrhea may be a limiting factor.

Treatment of Hypomagnesemia

Conversion Factor: 1 mmol = 2 mEq = 24 mg of elemental magnesium = 240 mg magnesium sulfate

Hypophosphatemia

Hypophosphatemia is probably the most confusing because there are multiple products that contain different amounts of phosphate. Because I am awesome and generous, here is a little refresher of the common phosphate products and their specific electrolyte concentrations:

Now that we’ve reviewed the phosphate products, let’s talk about hypophosphatemia.

Normal Phosphate Levels: 2.8 to 4.5 mg/dL

Hypophosphatemia classifications

Mild: 2.0 to 2.5 mg/dL

Moderate: 1.0 to < 2.0 mg/dL

Severe: < 1.0 mg/dL

Common causes of hypophosphatemia

Medication-induced: antacids (specifically aluminum and magnesium-based antacids), H2 receptor blockers, PPIs, niacin, osmotic diuretics

Other causes: steatorrhea, chronic diarrhea, hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, refeeding syndrome

Common phosphate replacement products

1st-line: potassium phosphate or sodium phosphate

Treatment of Hypophosphatemia

Hypocalcemia

Having fun, yet? We’re almost done. Let’s review the last common inpatient electrolyte deficiency - hypocalcemia.

Normal Ionized Calcium Levels: 4.4 to 5.2 mg/dL

Hypocalcemia classifications

Mild: 3.5 to 4.3 mg/dL

Moderate: 2.5 to 3.4 mg/dL

Severe: < 2.5 mg/dL

Whoa. Right now you may be thinking to yourself, “Um, I thought normal calcium levels were like 8.5-10 mEq/L…” Confusing, I know.

Thanks, Kip. (Image)

The key is that we’re discussing ionized calcium levels here. The ~8.5-10 mEq/L range mentioned above refers to normal total serum calcium levels. Total calcium is comprised of both ionized - aka free - and bound calcium since (as you may remember) about 50% of calcium is normally bound to proteins like albumin.

Ionized calcium is often considered the biologically active component. So if you’re really trying to get an accurate picture of the deficiency, especially if a patient is hypoalbuminemic, ionized calcium is your best bet! That being said, if you don’t have an ionized calcium level, your patient’s albumin level is relatively normal, and you have to estimate a corrected total serum calcium level, here’s how to do it:

Corrected total serum calcium level = Measured total serum calcium + 0.8*(4-patient’s albumin level)

You should keep in mind that this equation becomes less and less reliable the lower a patient’s albumin level is. This is because as the albumin level drops, more calcium ions bind each albumin - so it’s not a linear relationship. Calcium binding to albumin is also pH-dependent, so that’s another piece of the puzzle that can be difficult to account for.

Which brings us back to this - get an ionized calcium if you can!

Alright, now that we have that confusion hopefully out of the way…

Common causes of hypocalcemia

Medication-induced: calcium chelators, bisphosphonates, denosumab, cinacalcet, chemotherapy, foscarnet, fluoride poisoning

Other causes: hypoalbuminemia, acid-base disturbances, hormone dysregulation, vitamin D deficiency/resistance, osteoblastic metastases, sepsis/severe illness, surgery

Common calcium replacement products

1st-line: calcium gluconate

2nd-line: calcium chloride

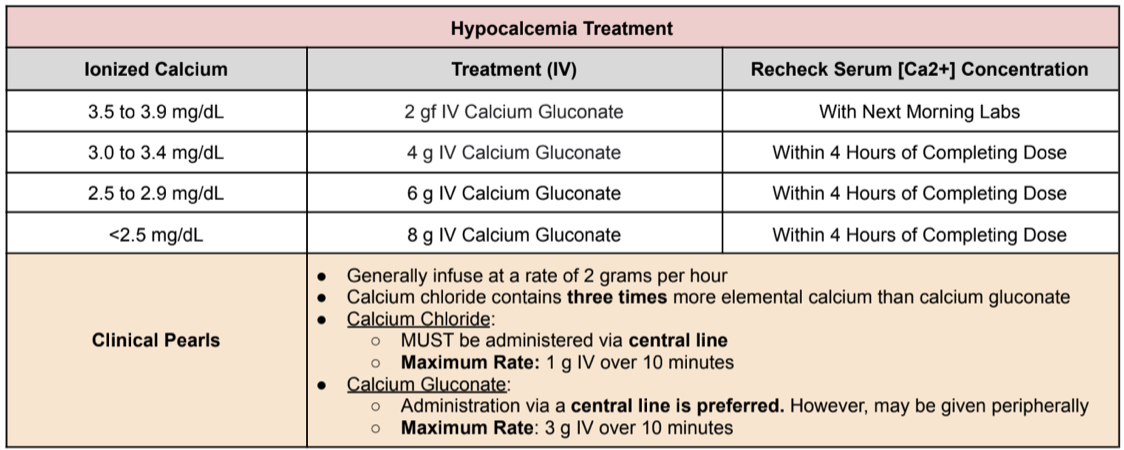

Treatment of Hypocalcemia

The tl;dr of Inpatient Electrolyte Replacement

Electrolyte deficiencies, specifically hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, and hypocalcemia can cause a variety of life-threatening emergencies, including cardiac arrhythmias, muscle paralysis, and seizures. Deficiencies can be caused by numerous factors, such as gastrointestinal causes, malnutrition, drug use, alcoholism, and hyperparathyroidism. But of course, this list is not exhaustive!

In general, mild electrolyte deficiencies can be replaced enterally, while more moderate/severe cases should be replaced parenterally. Oral magnesium supplementation may be initiated for mild hypomagnesemia, but beware the poor oral absorption and treatment-limiting adverse effect: diarrhea.

Remember that magnesium helps transport potassium and calcium ions in and out of cells. So a lack of magnesium can lead to low levels of both potassium and calcium. Check a magnesium level if you’re having a hard time normalizing either of those despite aggressive repletion.

Assess potassium levels to determine IV phosphorus product selection so as to avoid subsequent hyperkalemia. Also no bueno.

Finally, calcium chloride contains three times more elemental calcium than calcium gluconate, but whew, it’s a lot harder to administer than gluconate in terms of line type and maximum infusion rate. So a lot of the time, we just take the slow and steady route with gluconate rather than the harder chloride option.

Happy repleting!