What Every Pharmacist Should Know about Transdermal Fentanyl

Steph’s Note: Dr. Rebecca DeMoss was born and raised in Albuquerque, NM. She received her Bachelor of Science degree cum laude in Biology in 2010 and her Doctor of Pharmacy degree in 2014 from the University of New Mexico. Dr. DeMoss completed a partial residency at the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center. During her residency, she realized that hospital pharmacy was not for her, and this realization led her to long-term care pharmacy. She began her career with PharMerica Pharmacy in 2015 and has enjoyed all aspects of long-term care ever since. (FYI, the views in this blog are her own, and not those of PharMerica, nor of any person or organization affiliated or doing business with PharMerica.)

In response to increasing inappropriate prescribing of transdermal (TD) fentanyl, Dr. DeMoss created education surrounding this high-risk medication, building from her own colleagues all the way to a presentation at her local New Mexico Health-Systems Pharmacy Annual Balloon Fiesta Symposium this coming October.

In her spare time, she loves watching any MCU movie or binge-watching Netflix and Amazon Prime originals with her husband.

And with that, I’m going to let Rebecca take it away!

Well hey tl;dr fans! I am beyond excited and honored to be able to write for tl;dr and share my enthusiasm regarding this important information. I sincerely hope you enjoy this post and are able to use this information in your practice.

I want to start off with a patient's story that has forever changed my life. It ultimately encouraged me to create this blog as well as other educational presentations to spread awareness regarding this potent narcotic and trending dangerous prescribing patterns. I first want to give a shout out to my friends and family whose support through my creation of these presentations and blog has been unwavering.

I also want to thank Dr. Mary Lynn McPherson. She has authored 2 editions of Demystifying Opioid Conversion Calculations: A Guide for Effective Dosing. These books are absolutely amazing and have aided me in many opiate clinical kerfuffles. Between her numerous examples and detailed illustrations, you will find that maybe opioid dosing conversions are not that confusing ... maybe. (Btw, tl;dr has also broached the topic of pain management in this post if you need a refresher!).

The Fentanyl Patient Who Changed My Life

His name was AG. He was an 88 year-old male resident of one of our assisted living facilities (ALF). He received a prescription for a 25mcg TD fentanyl patch from the local Emergency Room after a ground level fall with associated rib fractures.

There was something unsettling about the prescription in my hand, so I decided to use other resources to verify the validity of the prescription. Being a long-term care pharmacy, we are exempt from running a narcotic prescription fill history using the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP); however I felt in this situation, the PDMP would be the best resource.

The report revealed he had not filled any narcotic prescriptions in the past year. I quickly thought I must have entered an error in the report, so I ran it again. However, the report did not change, and my heart sank. I was about to dispense this extremely potent TD fentanyl prescription to a completely opiate naive patient. If one of the nurses were to administer the medication, it most certainly would result in a lethal overdose.

I immediately called the Emergency Room to further discuss the validity of prescription with the physician. His immediate response was that AG was not opiate naive because he received 3 intravenous (IV) push doses of fentanyl, and he also had a codeine allergy. For these reasons TD fentanyl was the only option. I asked him if he wouldn’t mind holding while I verified this allergy with the ALF nurse. The patient only reported mild nausea and stomach upset while taking hydrocodone/acetaminophen when he was younger.

I reminded the physician that there is no currently accepted conversion factor between IV and TD fentanyl. Also, with the mislabeled allergy to codeine, we could confidently use another less potent narcotic. After some discussion about the IV to TD fentanyl conversion, he agreed and changed the prescription to oxycodone. After filling the new prescription, I called a pharmacy team meeting and discussed the severity of the situation with our entire staff. With tears in my eyes, I expressed how close we were to dispensing a lethal drug error and how important it is to be knowledgeable and work for our patients.

This patient has changed my life in so many ways that I can not begin to describe. This case demonstrates the most common inappropriate prescribing errors associated with TD fentanyl. We will be discussing these errors more in depth, and hopefully, by the end of this article, you can confidently catch these errors and save lives.

Error #1 - Prescribing of TD Fentanyl to Opiate Naive Patients

The FDA published a Health Care Advisory in 2007 that provides recommendations and clinical guidance for prescribers about this high-risk medication. The first recommendation is that the use of TD fentanyl is contraindicated for pain control in opiate naive patients. TD fentanyl is only indicated for opiate-tolerant patients and for chronic severe pain. But what is opiate-tolerance? Can you honestly define it?

Well, according to the FDA, opiate-tolerance is defined as a patient who has been taking daily, for one week or longer, at least 60mg of oral morphine, 30mg of oral oxycodone, 8mg of oral hydromorphone, 25mg of oral oxymorphone, or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid. In other terms, a patient must have been on the aforementioned milligrams daily or morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to begin TD fentanyl therapy.

Table 1 below is my go-to reference when initiating or converting patients to TD fentanyl.

Table 1 is the FDA’s recommendations for the total daily opiate dose required to begin or convert to a particular strength of TD fentanyl.

However, there are a few deficiencies in Table 1 that we need to be aware of:

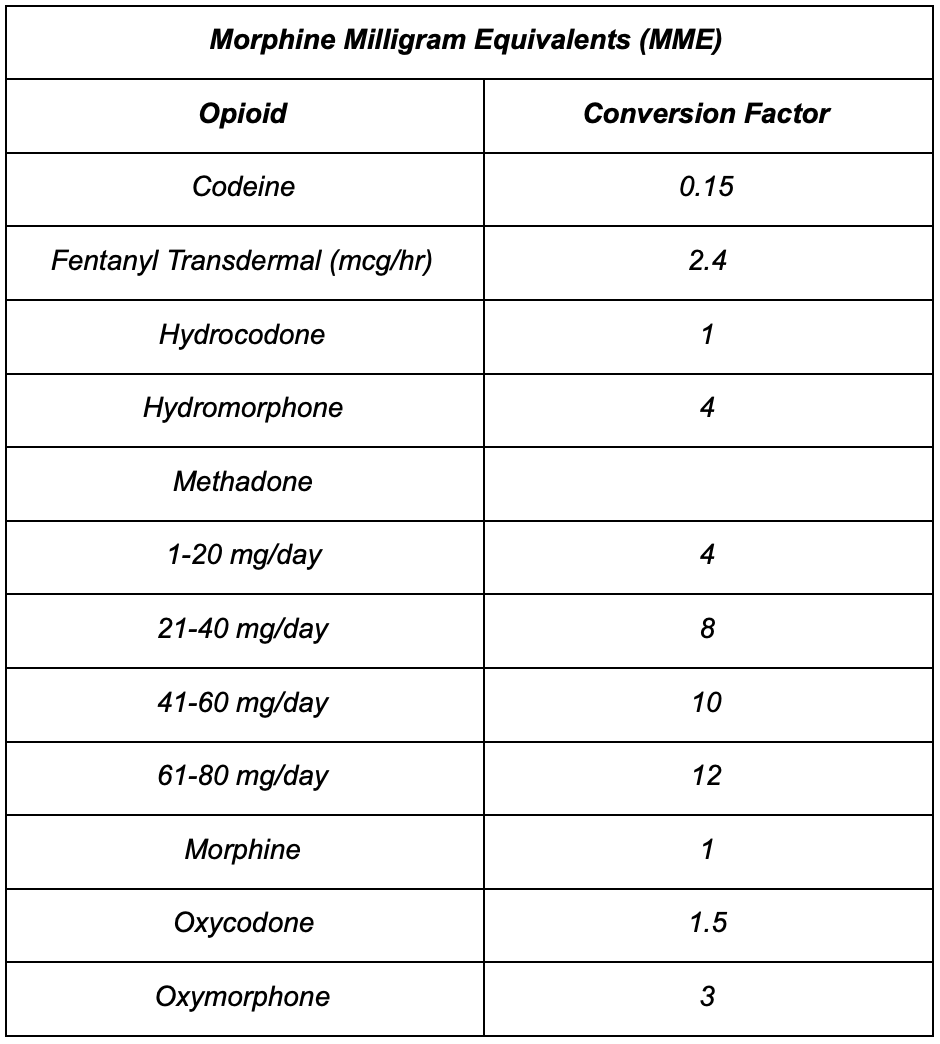

Table 2: Mathematical conversion factors between opioids

According to Dr. McPherson, Table 1 may be conservative. She recommends to convert every 2mg of morphine to 1mcg of TD fentanyl. Using this conversion guideline, 100mg of morphine will convert to a 50mcg/hr dose, however the FDA guidance suggests 100mg should convert to a 25mcg dose.

Confusing? I agree.

Nonetheless, there is one practice we can all agree on: start low and go slow. I firmly believe both approaches are correct, and, as always, considering the patient history and demographics will provide the best guidance to the correct dose.

A very common narcotic is not included in the conversion table. You may have guessed it: hydrocodone/acetaminophen. This has become a hot button topic at my pharmacy. I have had multiple providers inquire about converting a long-term hydrocodone/acetaminophen patient to TD fentanyl. However, according to the FDA conversion table, this practice is not currently defined.

In some cases, I believe there’s a need to walk outside the lines of FDA recommendations. For example, patient BG has been taking hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325mg, 1 tablet by mouth every 4 hours scheduled. The total daily hydrocodone dose for BG is 30mg. Using the nostalgic mathematical conversion factors (see Table 2 to the left), hydrocodone/acetaminophen to morphine is a 1:1 ratio. This means 30mg of hydrocodone/acetaminophen is equivalent to 30mg of morphine.

The current FDA table (aka Table 1) starts conversions to TD fentanyl at 60mg of MME, so how should we guide the prescriber when this patient’s MME is only 30mg? Well, at our pharmacy, I have decided to extrapolate the current TD fentanyl FDA conversion guidance table to Table 3 below.

Table 3: An extrapolated version of the TD fentanyl conversion table that includes MMEs < 60 mg/day.

This extrapolated version includes dosing guidelines for MME of 30-59. Most of the hydrocodone/acetaminophen cases I have converted have fallen in this range, and I have become comfortable recommending the TD fentanyl 12mcg/hr dose. (You must be thinking that I have lost my mind, but let’s stop and think about some potential benefits.)

First, the patient is taking 6 tablets per day just in their pain regimen. Pill burden is a real problem, and this patient may neglect their other medications which could hinder their other comorbidities and overall health. Second, this is a decent amount of daily acetaminophen potentially affecting their liver health. Removing the 2,000mg of acetaminophen may have additional benefits. There are many other pros and cons to this debate; however, my consistent recommendation is to open the discussion with the patient and provider to make the best decision for each patient.

Error #2 - IV to TD Fentanyl Conversion

As we saw with AG, prescribing TD fentanyl was completely contraindicated once we identified him as opiate naive. The FDA recommends that TD fentanyl is contraindicated in the management of acute intermittent or post-operative pain due to the high risk for serious life-threatening respiratory depression and death. Therefore, any individual receiving short-term IV fentanyl pushes is never considered opiate tolerant. (Now if we’re talking IV fentanyl pushes in the setting of patient-controlled analgesia, which may also have an associated continuous infusion, that could be a different story! Hold for a second on that one.) The physician in AG’s case incorrectly concluded that AG would be a good candidate for TD fentanyl because he had been given 3 doses of IV push fentanyl.

There is currently no accepted conversion factor or process to convert IV push to TD fentanyl. However, if the patient is receiving a fentanyl continuous infusion, Dr. McPherson has many recommendations to approach the conversion correctly and safely. (PS: for those who cannot wait, it is on page 102 in her 1st version of Demystifying Opioid Conversion Calculations: A Guide for Effective Dosing.)

So the next time a patient is filling a TD fentanyl prescription from the ER, you might want to consider this potential error. You can be prepared with this life-saving FDA recommendation to enable you to have an educated conversation with the physician.

Error #3 - Mislabeled Codeine Allergies

Another increasing error is the ubiquitous mislabeling of codeine allergies. According to this 2006 US Pharmacist article, as many as 9 out of 10 individuals labeled with a codeine allergy do not have a true allergy. Unfortunately, if an individual is labeled with this allergy, prescribers are then forced to seek alternative (possibly more potent) narcotics.

Table 4 shows the chemical structures of the 5 classes of opioids. The first column of phenatherenes contains most of our currently available oral/injectable opioids and their metabolites. Thus, if an individual has a codeine allergy the only other available opioids are listed in the additional 4 columns. Of course the diphenoxylate and loperamide aren’t really for pain (indicated for diarrhea), so they’re out. The other 3 columns have options like methadone, meperidine (Demerol™), tramadol (Ultram™), tapentadol (Nucynta™), and fentanyl.

Table 4: Classes of opioids grouped by chemical structure and risk of cross reactivity.

Now let’s think like a provider.

If our patient has mild to severe pain and has a codeine allergy, most providers will automatically discount methadone due to its potency, tricky pharmacokinetics, and prescribing regulations. They will also discount meperidine due to its side effects profile and lack of knowledge with this medication. Now consider tramadol and tapentadol. Most providers have reported tramadol as an insufficient pain medication for treating moderate to severe pain, and tapentadol is currently only available as brand name Nucynta™ and is extremely costly.

That leaves, you guessed it, fentanyl.

And as an added benefit, it is available as a TD patch. While this may not be the thought process of every provider, this does give us a clearer picture of how a provider may believe they only have one choice to prescribe the extremely potent TD fentanyl for patients labeled with a codeine allergy. For this reason and many more, it is every provider's responsibility to identify the validity of a listed allergy.

I bet you’re thinking, “That is a great idea, but how am I going to achieve identifying the validity of every codeine allergy?”

Well, let’s talk about allergic reactions, and hopefully we’ll be able to mitigate at least a few of these misconceptions. It is reported in clinical practice about 30-60% of patients receiving opioid therapy will develop nausea and/or vomiting at the start of therapy; however, they will also develop tolerance (and symptom dissipation) within 5 to 10 days. Due to the high prevalence of these adverse drug reactions, it is highly likely that this is a potential reason for the ubiquitous inappropriate allergy labeling. According to Pharmacy Times, the prevalence of a true anaphylactic codeine reaction is less than 2% of the US population.

Currently, there are three categories of allergic reactions we need to discuss:

True allergy

A pseudo-allergy

An adverse drug reaction (ADR)

Table 5: Types of reactions to medications

A true allergy is defined as an IgE +/- T-cell mediated cellular response causing a cellular cascade of immunomodulators resulting in a variety of severe manifestations. An example of this is anaphylaxis. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) is another example of a severe reaction to a medication, although the pathogenesis and involvement of T cells is not yet fully understood.

For anaphylaxis specifically, the recommendation is to treat using epinephrine. For all severe reactions, including both anaphylaxis and SJS, discontinuation of the suspected culprit and use of alternative medications are necessary.

A pseudo-allergy is thought to be a histamine-related cellular response, although the complement system may also be involved. These types of reactions cause typical manifestations like itching and rashes, although they can also lead to more severe clinical pictures that mimic anaphylaxis. Treatment modalities include antihistamines and/or steroids. In many cases a patient’s immunologic response causes the individual to document this medication as an allergy. This is the perfect example of an individual being inappropriately labeled as “allergic”, which, depending on severity, may be manageable with pre-medication.

ADRs are the third most common reason a patient is labeled with an allergy. ADRs can occur with any medication, and can cause a variety of symptoms. However, there are many steps individuals can take to manage the ADR safely and continue taking the prescribed medication.

Error #4 - Under Utilization of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP)

By now I hope you all have heard of and used the PDMP. However, if you haven’t, it is a program the captures an individual's narcotic and benzodiazepine fill history over the course of a specified time period. Below is a screenshot of New Mexico’s PDMP.

I am in love with the PDMP for many reasons, the main reason being the clear and concise narcotic fill history it reveals. The report shows everything we need to know to validate if a patient is opiate-tolerant and a candidate for TD fentanyl therapy. As previously mentioned, some pharmacies and practices are exempt from running the PDMP. For this reason, I included this as another common error.

Although a pharmacy/practice may be exempt, this omission creates an environment of under-utilization of a life-saving aid, increasing the risk for missing a life-threatening error. Personally, I run the PDMP on EVERY new start TD fentanyl prescription at my practice. I encourage everyone in any healthcare field to utilize the PDMP!

When all else fails… Naloxone (Narcan™)

(Image)

I have had many intense clinical discussions with a variety of health care providers, and I always have an ace in my back pocket. That’s right - naloxone (Narcan™).

For the situations where you have tried your hardest to convince the provider that TD fentanyl may not be the best option, a prescription for naloxone may give you peace of mind and potentially save the patient’s life.

As of June 2019, New Mexico passed an update to the Senate Bill 221 (NMSA 24-2D-1, 3) adding new language to the Pain Relief Act. This update mandates that all healthcare providers who prescribe, distribute, or dispense opioids must educate patients regarding opiate overdoses and co-prescribe an opiate antagonist. The opiate antagonist must be prescribed with EVERY opiate prescription that is a 5 days supply or greater and on an annual basis for chronic pain patients. Also in New Mexico (and many other states), pharmacists may have prescriptive authority for naloxone.

Whatever avenue is available for you, if you are feeling uncomfortable filling a TD fentanyl prescription, your suspicions may be warranted, and the recommendation for a co-prescription of naloxone is always a welcome suggestion.

Then the question becomes which form should we recommend? Currently there are four dosage forms available for naloxone, and they are listed below in Table 6.

Table 6: Currently available naloxone products. MAD = mucosal atomization device

There are many factors to consider when recommending this product, but my main suggestion is to always put the patient first. Each patient is different, so allow these formulary differences and monetary considerations to guide your decision.

C&C - Clinical Pearls and Conclusion

I wanted to end with some vital clinical pearls that are important to include with every TD fentanyl prescription.

ABSOLUTELY NO CUTTING

The lidocaine patch (Lidoderm™) is the only patch available on the market that can be cut.

Do not directly apply patch to site of pain

Apply to intact non-irritated, not shaved, flat skin surface

Chest, back, or flank of upper arm are the best locations

Caution when elevating body temperature

Not recommended for use during hot baths, under heating blankets or pads, in hot tubs/saunas, etc.

Remove patch prior to MRI procedures

Potential for burns due to metallic pieces within the patch

Careful monitoring in elderly, cachectic, or debilitated patients

Caution use in cachectic patients as decreased body fat reduces the drug’s ability to form the desired subcutaneous reservoir

This could lead to altered pharmacokinetics, especially absorption, and possibly shorter duration of effect

Renal and hepatic impairment

Moderate impairment - decrease initial dose by 50%

Severe impairment - use not recommended

So whether it is creating a personal or professional protocol or building relationships with your healthcare team, together we can decrease these dangerous prescribing patterns and save lives. From the bottom of my heart, I thank you for taking the time to read my story. Please do not hesitate to contact me with questions or concerns, I can do this all day. Happy reading tl;dr fans!

(Image)